Post-pandemic China resurgent [LNG Condensed]

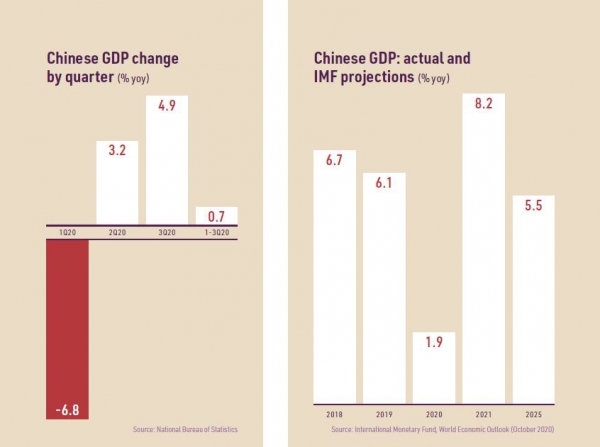

The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook predicts that China will be the only major economy to grow in 2020. While the IMF’s October forecast has global GDP falling by 4.4% year on year in 2020, Chinese GDP is projected to grow by 1.9%. This is in line with the 2% growth rate for 2020 projected in October by the People’s Bank of China.

The projection is also in line with official GDP data for the year to date. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), a 6.8% fall in GDP in the first quarter of 2020 was offset by growth of 3.2% in the second and 4.9% in the third, meaning the economy grew 0.7% during the first nine months of 2020. The recovery was driven by services, construction and, more latterly, industrial activity.

Looking ahead, the IMF projects that growth will rebound to 8.2% in 2021 and settle at around 5.5%/yr by 2025. The latter figure is in line with President Xi Jinping’s target of doubling Chinese GDP by 2035.

China’s economic resurgence has gone hand in hand with increased demand for energy, and especially natural gas. The increase in gas use has resulted not only from the growth in economic activity, but from the government’s policy of reducing pollution and emissions by replacing coal with gas in various applications in the industrial, electricity generation and residential sectors.

Gas demand

Gas’s replacement of coal in the industrial sector has been patchy, while its penetration of the electricity sector remains a meagre 3% of generation. But the residential sector has seen a more concerted switching strategy, especially in heating systems in the north of the country.

The programme admittedly got off to a rocky start in the winter of 2017-18, since insufficient gas and delivery infrastructure was available to meet all the new demand – more than 10bn m3/yr -- resulting from the conversion of more than four million small coal-fired systems in 28 northern cities.

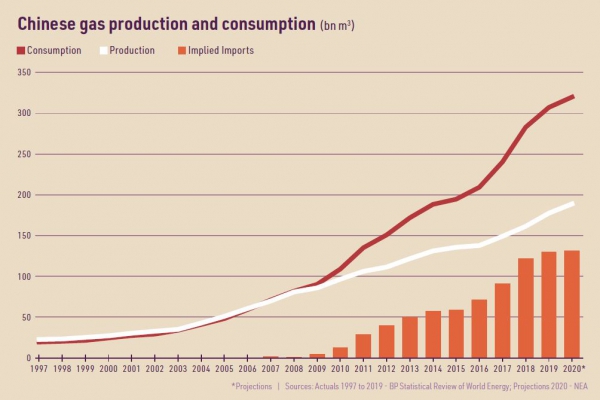

Gas demand in the first nine months of 2020 was up 3.6% year on year at 231bn m3, according to the National Development Reform Commission. This is in line with a September projection by the National Energy Administration (NEA) that put 2020 demand up more than 4% at 320bn m3.

Strong recovery

The modest increase reflects the severe impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on gas demand in the first half of the year, but year-on-year growth in consumption is now much higher.

In November, the official China Daily newspaper reported that PetroChina, the listed subsidiary of the state energy company CNPC, was planning to supply 98.67bn m3 of gas during the 2020-21 winter heating season, up 10bn m3 or 11.3% year on year. Meanwhile, fellow state energy company Sinopec was quoted as saying that total winter gas demand would increase by 11.8bn m3 year on year to 148bn m3.

Growth is expected to remain strong in the longer term. In October 2020, PetroChina projected that demand would reach 620bn m3 in 2035. The same level had been projected for 2035 by the CNPC Economics and Technology Research Institute in September 2018, while CNPC’s 2019 projection for 2035 was little different at 610bn m3.

Gas production

How much of the increase is met by imports will depend on gas production, which has increased at a relatively fast rate since 2016. NBS data shows that gas output reached 153.4bn m3 between January and October 2020, up 9% year on year. In September, the NEA estimated that calendar 2020 output would reach 189bn m3.

The growth in output is well up on the sluggish increases in the first half of the 2010s, but still well below the increase in gas consumption. The gap between output and demand has risen from just over 4bn m3 in 2009 to 130bn m3 in 2019.

There is a growing view within China that the gap should be reduced to limit import dependency and support domestic employment. This has fed through into some recent forecasts.

For instance, in October, PetroChina projected that the gap in 2035 would fall to 100bn m3, based on domestic supply reaching 520bn m3. The projection envisaged a modest increase in conventional gas production to 220bn m3, with the remaining 300bn m3 coming from much-increased volumes of shale gas, coalbed methane and coal-based synthetic gas.

This is a more bullish view of the potential contribution of unconventional gas production than most forecasts. As recently as August 2019, CNPC projected that total gas production would only reach 300bn m3 in 2035. It is also highly optimistic given shale gas, CBM and synthetic gas together contributed only around 25bn m3 in 2019, with volumes having grown relatively slowly because of physical, technical and cost issues.

Some recent developments may favour increased production of unconventional gas. For instance, access to the Chinese gas transmission network has been problematic for some producers in the past, since many are based in areas distant from the main demand centres.

But, in September, the new national pipeline operator PipeChina took over the state energy companies’ transmission networks, which may level the playing field for unconventional gas producers and allow them better access to the market.

This is likely to have limited impact unless the technical, cost and other issues are resolved, making it too early to say whether the faster rate of increase in shale gas output in recent months is sustainable.

The need for imports

Far from the gap between Chinese gas output and demand shrinking, it could in fact grow substantially. This is not least because of the fuel’s perceived role as a bridge to achieving China’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060. Gas demand of 620bn m3 in 2035 could easily be required if progress is to be made towards this commitment, not least because of the need for increased gas-fired generation to help reduce coal-fired output.

Combined with the problems likely to be met expanding unconventional gas output, this suggests that CNPC’s 2019 projection of an import requirement of 310bn m3 in 2035 may be more likely than the 2020 projection of 100bn m3.

Most other forecasts are at the upper end of the range. BP, for instance, projected in 2019 that 274bn m3 of imports would be needed in 2040.

Pipeline prospects

Gas imports will include both LNG and piped gas. The latter is currently delivered by pipelines from Central Asia (55bn m3/yr of capacity with gas supplied from Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), Myanmar (12bn m3/yr of capacity) and, most recently, Russia (capacity building to 38bn m3/yr by 2025).

China imported just over 50bn m3 of piped gas in 2019, but PetroChina has indicated that imports in 2020 will be at least 5% lower. The anticipated fall primarily reflects the fact that for most of 2020 the price of spot LNG has been lower than that of Central Asian gas supplied under long-term contracts.

The price of LNG and the desire for supply diversity will largely determine the future level of China’s piped imports. Apart from the 105bn m3/yr of existing pipeline capacity, it is planned that, by the early 2030s, a second 38bn m3/yr pipeline will be built from Russia and a 30bn m3/yr fourth line will be built from Central Asia.

If these additional pipelines are implemented, pipeline import capacity in the mid-2030s could reach 173bn m3/yr, leaving a minimum LNG requirement of 140bn m3 in 2035. However, there is no guarantee that the new pipelines will be built, while piped imports have rarely approached the capacity of the pipelines. LNG requirements could thus be significantly higher than 140bn m3/yr, potentially reaching 200bn m3/yr or more in 2035.

LNG accounted for almost two-thirds of the 135bn m3 of total gas imports in 2019, and has increased strongly in 2020, despite the Covid-19 pandemic. General Administration of Customs data indicates that LNG imports increased by 10% year on year in the first nine months of 2020, with the increase being driven by low prices.

Based on deliveries for the year to date, LNG imports could reach a record 67 million mt (91 bn m3) in 2020. This is well within the 74.55 million mt/y of operating LNG import terminal capacity.

Most of the regasification facilities that were due to enter service in 2020 have been delayed to 2021 as a result of the pandemic. However, with a large number of terminals under construction or planned, there is no reason to think that 200bn m3 and more could not be imported in 2035.

Changing market

The Chinese LNG market is changing rapidly, with new players appearing and existing ones reinventing themselves as the gas market is liberalised. Market access is expected to gradually improve, as a result of PipeChina’s control of 10 operating and under construction LNG import terminals with 32 million mt/y of capacity as well as the national transmission lines.

Many Chinese players who to date have been limited to the distribution and supply end of the gas business are looking to purchase LNG directly, delivering it to their customers either through third-party facilities or their own terminals.

What this will mean for international LNG suppliers remains to be seen, with key uncertainties being how relations with the US evolve following the presidential election and the acrimonious dispute with Australia. But one thing is certain – while more Chinese players will be seeking to buy LNG, this will not affect their ability to drive a hard bargain in a market which will be by far the biggest source of global demand growth for some time to come.