Postponed: climate change action [Gas in Transition]

The upheaval in global energy markets resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as high inflation and the energy crisis that followed rapid economic recovery as the world emerged from COVID-19, are in danger of derailing the drive to bring climate change under control. The priority now appears to be security and affordability of energy supplies at the expense of the climate, so much so that the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s new report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, has barely made the headlines.

IPCC’s report warns that “deadly with extreme weather now, climate change is about to get so much worse. It is likely going to make the world sicker, hungrier, poorer, gloomier and way more dangerous in the next 18 years with an unavoidable increase in risks.” And more: “There’s real existential threats… all the risks are coming at us faster than we thought before… More of it will get really bad much sooner than we thought before…half of the world’s people are highly vulnerable to serious impacts from the climate crisis.”

Dire warnings, so why is it that they are not being heard? Clearly it has been overshadowed by the equally dire news coming out of Ukraine. But it is more than that. In the aftermath of US and EU sanctions, and likely with more to come, security of energy supplies has now become the top priority, especially in Europe.

As John Kerry said recently, the geopolitical tensions of the Russia-Ukraine war could “hamper international efforts to curb global warming”, with high energy prices making consumers and governments “wary of taking tough measures needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The decisions being taken now in response to fast evolving situations and global polarisation between US and the EU on one side and China and Russia on the other will reshape the future of energy markets and trade, and of course plans to combat climate change, permanently.

IPCC report

IPCC is warning that even if the world achieves the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, extreme events, such as wildfires, droughts, floods, will continue. Some are already irreversible and the world needs to adapt accordingly.

As a result, IPCC recommends that in addition to measures to cut emissions, the world must do more to adapt to such changes. Not enough is being done at present and without action being taken now, “threats will grow too severe for any adaptation effort to allow life to proceed as normal.” The dire warning is that there is no more time: “it is now adapt or die.”

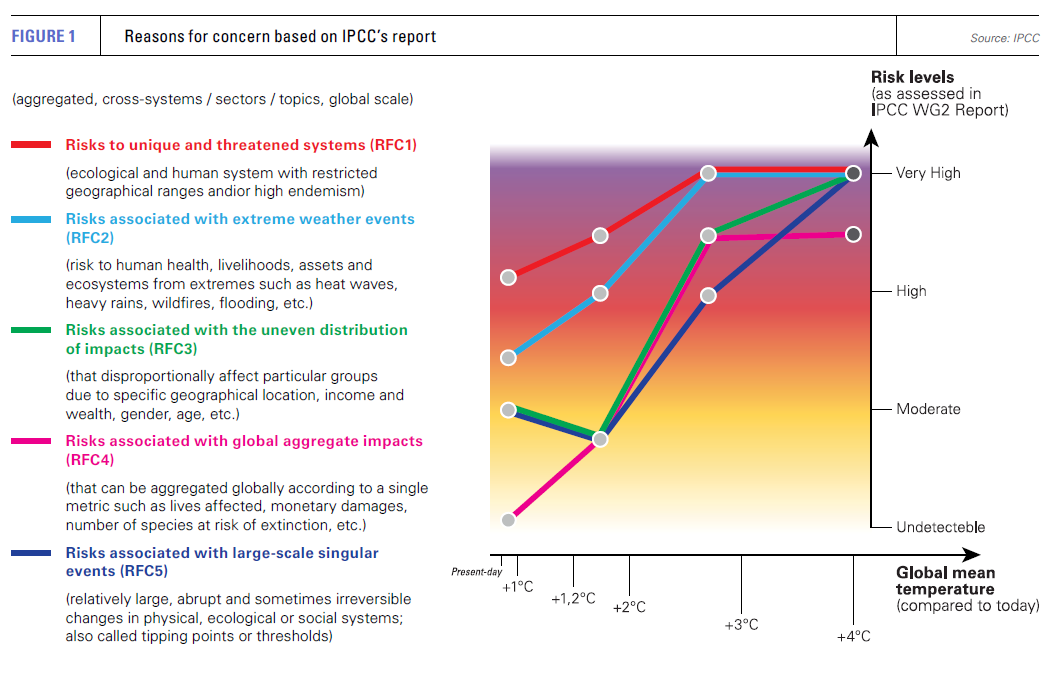

Without drastic action to cut emissions, recent estimates put global warming to between 2°C and 4°C by 2100, with global climate risk increasing to between two and four times. The reasons for concern are summarised in Figure 1.

IPCC plans to release another report in April on measures to reduce fossil fuel consumption and emissions, and on alternatives including renewables, hydrogen, nuclear, energy efficiency and carbon capture utilisation and storage.

The aim is to produce a final report in October in time for COP27. The key message will be that the world is running out of time.

Despite that, the immediate concern appears to be the rapid unfolding of the far-reaching events reshaping global geopolitics, energy markets and energy security as a result of the war in Ukraine. Climate change targets are ‘temporarily suspended’. COP 27 is too far away.

Europe’s decision time

The EU has been forced to make monumental decisions. It plans to reduce reliance on Russian gas by two-thirds this year and end dependence on Russian fossil fuels altogether by 2027. This is by no means easy. In addition to investing a lot more and accelerating implementation of renewables and hydrogen, it requires a return back to coal and nuclear. But even then, achieving such targets will be challenging and a substantial cost to European consumers for a prolonged period, likely for the rest of this decade.

During this period, the risk of disruption to European energy supplies will persist, maintaining high oil and gas and energy prices and impacting the economic recovery.

But despite this, Europe is under increasing pressure to make a clean break from Russian fossil fuels as soon as possible. Such a decision will have a dire impact on prices of everything, from energy to food to all manner of commodities and products.

Goldman Sachs estimates that stopping all gas imports to Europe “could see Euro area GDP growth fall by 2.2% in 2022 relative to our baseline forecast, with sizable impacts in Germany -3.4% and Italy -2.6%.” The German economic and energy minister, Robert Habeck, warned an immediate stop to supplies “could hurt Germany’s population more than Putin…Boycott of Russian gas and oil could cause mass poverty in Germany.”

With renewables still limited by intermittency and green hydrogen and long-duration batteries still having some way to go before serious scaling up, the transition to cleaner forms of energy at scale will take time, probably well into the next decade. Reliance on fossil fuels will continue.

Replacing all Russian gas imports is all but impossible in the near-term. That would mean increasing use of coal and of course increased emissions. Climate change pledges will have to wait.

Conflicting messages

At CERAWeek by S&P Global in Houston early March, one message was “don’t let an oil shock or invasion of Ukraine distract anyone from the climate fight.” But at the same conference, US secretary of energy Jennifer Granholm, talking to oil industry leaders, said “We are on a war footing — an emergency…That means you producing more right now, where and if you can.”

John Kerry, US climate envoy, implored the conference delegates not to lose sight of the climate fight, but there was no question that “national security and energy security clearly moved to the forefront,” overshadowing climate change.

Pressure on the US administration to relax permitting and environmental rules to enable new infrastructure to be built to boost US energy exports to Europe is increasing.

In the UK, prime minister Boris Johnson and oil industry CEOs discussed “increasing investment in the North Sea oil and gas industry and boosting supply of domestic gas. This includes how the UK can remove barriers facing investors and developers, and help projects come online more quickly.” The plan is to make changes to legal net zero climate change commitments in order to accelerate licensing for new North Sea oil and gas fields on the basis of ‘national security considerations’. But there is also a drive to accelerate implementation of onshore wind and solar.

In Europe there is a surge in investment in clean energy. But the question is whether the energy transition can actually happen that rapidly. The Ukraine war is ushering in new priorities. The immediate concern is energy security as Europe commits to a future independent of Russian fossil fuel imports. Renewables and hydrogen are unable to react that quickly. As a result, nuclear and coal are experiencing a resurgence that started even before the war, as a reaction to the post-pandemic energy crisis. In Europe, coal power generation increased by 18% in 2021 and it is experiencing a further boost as a result of the war. Even Germany’s Habeck, hailing from the Green party, said “Europe may be forced to burn more coal in the face of…spiralling gas prices.”

The war in Ukraine is clearly upending many carefully planned future energy strategies. But politicians are sending mixed messages. On the one hand, they call for maximising production of fossil fuels to get rid of Russian imports, but on the other, the assurances needed to unlock investment are not forthcoming due to the fear of locking in future oil and gas use.

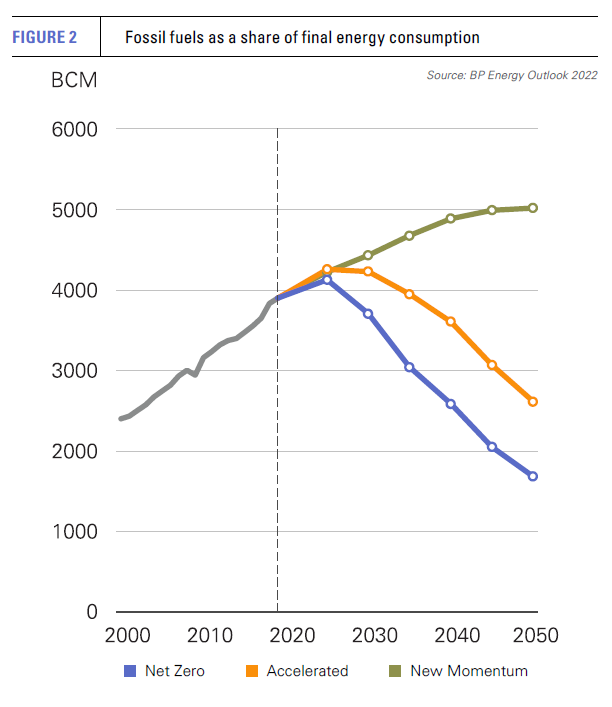

These conflicting messages need to be addressed sooner than later if the response to the energy crisis and the need to accelerate energy transition are to be sensibly planned. It is not one or the other – both are needed. And not just for a few years – energy transition is not happening as quickly or as easily as expected. As BP’s new Energy Outlook 2022 shows (Figure 2) under its “accelerated scenario”, fossil fuels will still be contributing over 50% of global final energy consumption even by 2040. On this basis, BP recommends that continuing investment in new upstream oil and gas is required over the next 30 years.

Energy transition still a priority

Many believe that the shelving of climate considerations will only be short-term, until the supply tightness is dealt with and energy security ensured. But these are not the only reasons. The energy crisis started before the Ukraine war and will continue until clean energy can stand alone without requiring back-up from fossil fuels. But this happy ending is nowhere near as yet.

Energy transition is still a priority but it will take its time. But as many point-out, “politicians need to be honest with the voters.” Getting rid of Russian fossil fuels and energy transition will be costly and may involve changing social habits. Energy prices are likely to remain high for some time. There is no going back.

As the Financial Times pointed out, “we need a grand bargain on energy – in a crisis, there is an opportunity for EU-US cooperation over smarter and safer sourcing.” Energy transition will not happen overnight and during that time “there’s no getting around the fact that it will need fossil fuels to bridge the gap.”

The US, but also Europe, “are coming around to the idea that the war in Ukraine and the global fallout are more important than environmental lines in the sand, or at least in the short term.”

In its report, titled No pain, no gain: The economic consequences of accelerating the energy transition, Wood Mackenzie said that “while an accelerated energy transition will pay off, both economically and environmentally, it will take time for the benefits to be realised, with much of the lasting economic benefits only materialising beyond 2050.” Further, energy transition technologies will come down in price over time, but the break point may not come before 2035. Hence the need to maintain the exploration and production of fossil fuels.

When the dust settles, hopefully by COP27 in Cairo in the autumn, governments will focus their attention on climate change – and the IPCC report – and come up with renewed plans to tackle carbon emissions and global warming. But for now, this is taking a back seat.