Project spotlight: Barcarena FSRU, Brazil [LNG Condensed]

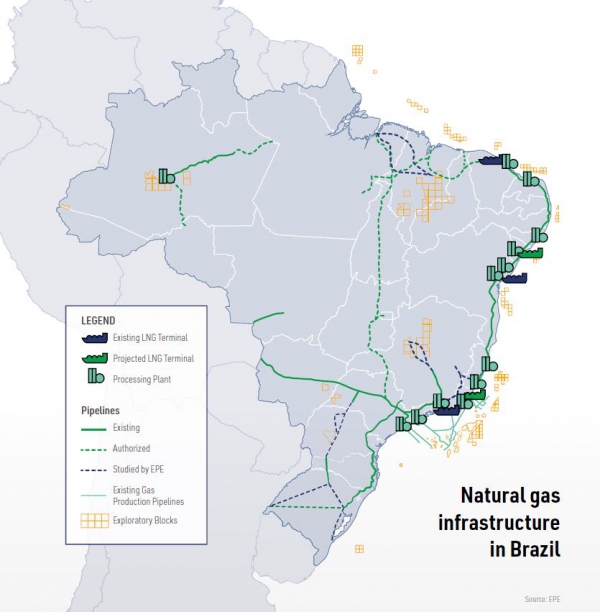

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world and a major gas consumer and producer, but its gas network is heavily concentrated in the south and east running predominantly along the coast. Northern Brazil, in contrast, has little gas infrastructure to speak of.

Yet the region has some major energy-intensive industrial concerns, which in the absence of gas rely predominantly on fuel oil. These include Norsk Hydro’s Alunorte alumina refinery plant, the largest of its kind outside of China.

Industrial processes such as alumina refining, cement and fertilizer manufacturing are notoriously difficult to decarbonise and long-term are looking to hydrogen as a potential solution. However, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions could be reduced much earlier by the extension of LNG supply chains to areas with little access to gas.

Norsk Hydro has pledged to reduce GHG emissions across its business by 30% by 2030, and made a commitment to the Para state government to run the Alunorte plant on gas in 2017. The conversion, made possible by the proposed Barcarena LNG project, will cut GHG and particulate emissions significantly at the plant and should also result in reduced fuel costs.

FSRU solution

The gas will be delivered via Golar Power’s Barcarena floating, storage and regasification unit (FSRU). Golar Power is a joint venture between Bermuda-registered Golar LNG and US-based Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners.

On July 23, Golar Power said it had signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Norsk Hydro to build the FSRU, which would be northern Brazil's first LNG import terminal.

Brazil currently has three LNG import terminals, all FSRUs: Bahia LNG, built in 2014 with import capacity of 3.8mn mt/yr; Pecem LNG, built in 2016 with capacity of 5.4mn mt/yr and the 3.4mn mt/yr Sergipe-Golar Nanook, which came into service in 2019. It also has a 5.6mn mt/yr FSRU under construction at Acu Port, according to International Gas Union data.

However, the FSRU will also serve the 605-MW Centrais Eletricas Barcarena (Celba) thermal power plant, which Golar Power was awarded a 25-year power purchase agreement for in October last year. The LNG-to-power project will be developed by Celba, a special purpose company that is 50% controlled by Golar PowerThe power plant will use modern H-Class gas turbines, with the power distributed to the Brazilian national electricity grid through the Vila do Conde substation nearby. Total investments for the power project are estimated at $430mn, of which Golar LNG’s share is $107mn.

Golar Power also wants to roll out an extensive LNG distribution network across the Para state and the wider region, to provide gas to industrial, commercial and transportation customers, which should again result in oil-to-gas switching, leading to early GHG emissions reductions.

Company networking

Golar Power has forged a number of partnerships for its planned foray into Brazil's gas market. In November last year it reached a deal with Norway's Hoegh LNG and Stolt-Nielsen on jointly developing the country's small-scale LNG market. And, earlier this year, it signed a protocol on constructing an import terminal at the Brazilian port of Suape.

The company has also entered into a pact to use gas tech firm Galileo Technologies' solutions for gas conditioning, distributed LNG production, LNG filling stations and regasification plants in the country. Galileo's Cryoboxes are used in North America by Edge LNG to capture gas from stranded wells, liquefy it, and truck it to market.

Brazil’s LNG market to grow

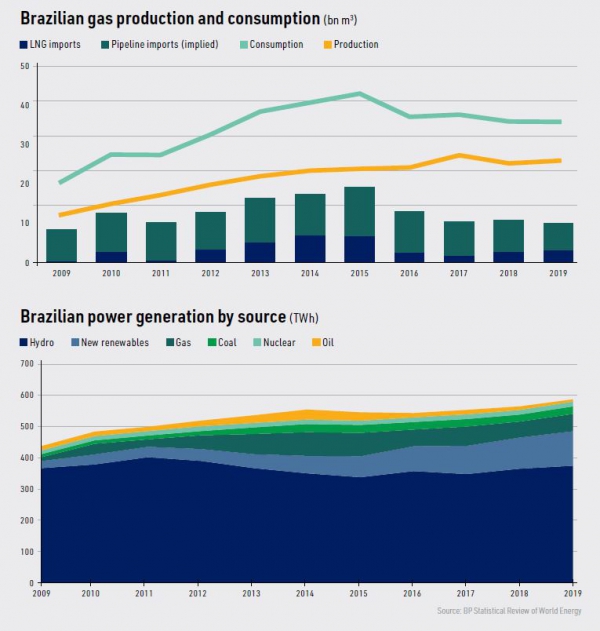

Over the past decade, Brazil has seen its natural gas consumption rise sharply from 27.6bn m3 in 2010 to a peak of 42.9bn m3 in 2015, before a gradual decline to 35.8bn m3 last year.

Its LNG imports, however, show a different trend. They climbed from 2.8bn m3 in 2010 to 7.1bn m3 in 2014 before also dropping to a low -- 1.7bn m3 in 2017 -- but in each of the last three years the country’s LNG consumption has increased, reaching 3.2bn m3 last year.

One of the reasons for this trend is that domestic gas production has stalled and is unlikely to be encouraged by the coronavirus pandemic and drop in energy prices. Domestic gross gas output in 2019 was 25.8bn m3, down from 27.2bn m3 two years earlier.

Brazil has been reinjecting the associated gas from its offshore pre-salt oil reserves to maintain and grow its oil production, so marketable gas production is not expected to rise much over the next eight years. Fitch Solutions, for example, expects just over 23bn m3 in 2028, up from last year’s 22bn m³.

Pipeline problems

At the same time, Brazil’s pipeline imports have run into problems. Brazil imports gas from Bolivia and Argentina. In the latter, low oil prices and economic instability have thwarted, so far, the country’s shale oil and gas ambitions, which are centred on the giant Vaca Muerta shale play.

Meanwhile, a long-term contract with Bolivian oil and gas company YPFB ended in March, and Petrobras, Brazil’s state oil and gas company, took the opportunity to reduce its offtake from 30mn m3/d to 20mn m3/d. Then, in June, the minimum offtake was reduced from 14mn m3/d to 10mn m3/d, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

The additional capacity will be opened to local distribution companies. However, it is not clear there will be much demand for it as LNG is cheaper than Bolivian gas.

Brazil’s enthusiasm for Bolivian gas has declined, partly because of upstream uncertainty in Bolivia itself – the country’s gas production fell 12.2% in 2019 – partly because of the cost of the gas and partly owing to political instability in Bolivia. In November last year, an attack destroyed a 200 metre section of the Carrsco-Cochabanba pipeline, an event which followed the exodus into exile of former Bolivian president Evo Morales.

Yet back in Brazil, gas consumption is rising and is likely to continue to outstrip domestic supply as more gas-fired power capacity is built: examples include Porto de Sergipe and Porto de Acu, which together total 4.5 GW and will be supplied by LNG.