Project Spotlight: Lake Charles LNG [Gas In Transition]

The end of March announcement that Energy Transfer, developer of the US Gulf Coast Lake Charles LNG project, had signed off-take agreements for 2.7mn mt/yr of LNG, was a major boost for the project. However, it still has some way to go before a final investment decision (FID) is taken, even though the offtake agreements anticipate a start-up as early as 2026.

The facility is located on the Calcasieu ship channel and the proposed conversion, which would extend the site by 240 acres, is fully permitted for three 5.5mn mt/yr LNG trains. Authorisation from the US department of energy to export 16.45mn mt/yr of LNG has also been secured. In addition, the plant’s location is well served by Energy Transfer's existing trunkline system from various shale basins, including the Haynesville, Permian and Marcellus Shale.

The facility is located on the Calcasieu ship channel and the proposed conversion, which would extend the site by 240 acres, is fully permitted for three 5.5mn mt/yr LNG trains. Authorisation from the US department of energy to export 16.45mn mt/yr of LNG has also been secured. In addition, the plant’s location is well served by Energy Transfer's existing trunkline system from various shale basins, including the Haynesville, Permian and Marcellus Shale.

Lake Charles is a promising project because it is based on a redundant LNG import terminal. This gives it a significant cost advantage as much of the infrastructure, from gas pipeline connections to deep water shipping berths and LNG storage tanks, are already in place.

Shale gas rewrote the future

It is easy to forget that the US faced a future in which it would enter the LNG market not as an exporter but as an importer, and a big one at that. A swathe of LNG import terminals were built based upon the expectation of domestic gas shortfalls.

The Trunkline LNG terminal, the proposed site of Lake Charles LNG, was one of the largest. Construction was completed in 1982 with two subsequent expansion phases ending in 2006. At this point, the terminal boasted two deep water berths, four LNG storage tanks and send out capacity of 1.8bn ft3/d baseload, rising to 2.1bn ft3 peak.

Along came shale gas and everything changed.

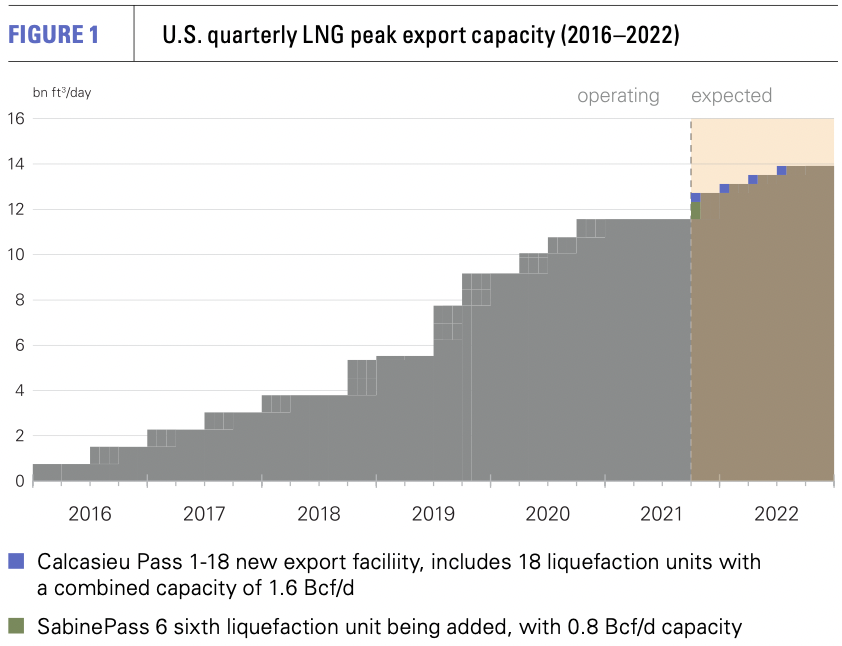

Demand for imported gas slumped and the US found itself with excess and rising production on its hands as more gas was produced alongside its booming oil shale output. Gas flows to Canada rose, there was a huge jump in exports to Mexico and, in 2016, with the start up of Sabine Pass, a new generation of LNG plants started to send US LNG around the world.

Demand for imported gas slumped and the US found itself with excess and rising production on its hands as more gas was produced alongside its booming oil shale output. Gas flows to Canada rose, there was a huge jump in exports to Mexico and, in 2016, with the start up of Sabine Pass, a new generation of LNG plants started to send US LNG around the world.

The existence of abundant gas supply and stranded LNG import terminals was a winning formula in terms of permitting, costs and speed to market. It allowed US developers to secure off-take agreements with buyers wary of the time-scales and higher risks of greenfield development both in the US and elsewhere.

Sabine Pass, Cove Point, Freeport LNG and Corpus Christi are all LNG import terminal conversions given a new lease of life by the change in fortunes wrought by shale gas.

Twists of fate

So why then is Lake Charles so far behind?

Back in 2015, Lake Charles LNG was looking good. Energy Transfer had secured a 100% off-take agreement from the UK’s BG Group. An FID on the 16.45mn mt/yr LNG plant was expected in mid-2016.

However, corporate developments intervened. Anglo-Dutch major Shell announced a $53bn acquisition of BG Group, which necessitated a renegotiation of the off-take agreement.

Shell wanted a direct stake in the project and off-take at the same level. A new deal was struck in which Shell and Energy Transfer both owned 50% of the project, and each would take 50% of the LNG produced. Energy Transfer had reduced its capital exposure, but now had just over 8mn mt/yr of LNG to market in order to raise finance for its share of the project.

Shell wanted a direct stake in the project and off-take at the same level. A new deal was struck in which Shell and Energy Transfer both owned 50% of the project, and each would take 50% of the LNG produced. Energy Transfer had reduced its capital exposure, but now had just over 8mn mt/yr of LNG to market in order to raise finance for its share of the project.

The prospect of an FID was put back to the end of 2020, but confidence remained high with the two partners opening the bidding process for an engineering contract in December 2019. Tender packages were issued for a lump sum turnkey contract. Energy Transfer said subsequently that bids had been received and were being evaluated.

Pandemic impact

However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic saw market conditions deteriorate. Oil and LNG prices plummeted. With a rash of investment decisions in new LNG plants around the world preceding the outbreak of the virus, a market that had appeared to offer steady long-term demand growth now seemed to be moving into a substantial surplus in the mid-2020s.

This created a hiatus in new investments, but, more crucially for Lake Charles, resulted in the withdrawal of Shell from the project altogether.

Shell, in 2020, instituted a $5bn cut in capital spending and suspended its $25bn share repurchase programme. Projects had to be dropped and the oil major announced its withdrawal from Lake Charles in March of that year.

Energy Transfer took full control, but now faced the task of finding buyers for the plant’s entire output. To do this, the company needed more time. Having, along with Shell, sought a five-year extension in 2019 from the US Federal Energy and Regulatory Commission (FERC), Energy Transfer found itself in February this year asking FERC for a further three years. This would give it until 2028.

War in Europe

The next episode in the saga could not have been more dramatic. Russia had for months been massing troops on the Ukrainian border, but most observers downplayed the likelihood of a full-scale invasion, despite the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and sustained support from Moscow for two breakaway regions in Ukraine’s east. Against expectation, the Russian army rolled across the Ukrainian border at multiple points in late February.

Sanctions followed as Europe faced up to its dependence on Russian oil and gas supplies. The result is a concerted effort by the EU and other European countries to reduce Russian gas imports, which means looking in large part to the LNG market.

The likelihood of a boom in European demand for LNG, not just this year but over the next decade, has not been lost on Chinese companies also seeking expanded LNG supplies. It is perhaps, therefore, no surprise that ENN, which operates China's first privately-owned LNG terminal in Zhoushan, and has an annual LNG distribution capacity of more than 10bn m3/year, has stepped up quickly to become Lake Charles LNG’s foundation buyer.

This, Energy Transfer hopes, will create momentum to secure further deals as confidence amongst buyers grows that the project can move forward on the timescale proposed. If it does, European and Asian buyers alike will see LNG supply grow, while the US gas sector will finally see another legacy import asset repurposed into a revenue-earning export plant.