Russia eyes petchems boost [NGW Magazine]

Russia’s largest oil and gas producers are moving into petrochemicals, adding value to exports and establishing a greater downstream hedge against volatile oil and gas prices.

Considering its vast hydrocarbon reserves, Russia’s petrochemicals footprint is minuscule, accounting for less than 2% of global supply capacity. This is set to change, with a raft of new projects due to come on stream over the coming years. These projects will mainly rely on ethane as feedstock, produced as a by-product of gas processing. Oil-derived naphtha, on the other hand, is proving far less popular.

Ethane has emerged as a lower-cost solution than naphtha thanks to a surge in Western Siberian gas production in the last few years, driven by higher demand in Europe. Oil output, by contrast, has stagnated since Russia began co-ordinating supply with Saudi Arabia and other Opec+ members three years ago. Naphtha will become even scarcer as Russia this month makes a record cut to its oil supply to 8.5mn b/d under the new Opec+ deal, from 11.3mn b/d at present.

The Russian government is keen to support the expanding petrochemicals segment, as it will help diversify the country’s export revenue mix. It has introduced a package of measures over the past year to incentivise development, with the goal of doubling national petrochemical production to 20mn mt/yr by 2030.

Key projects

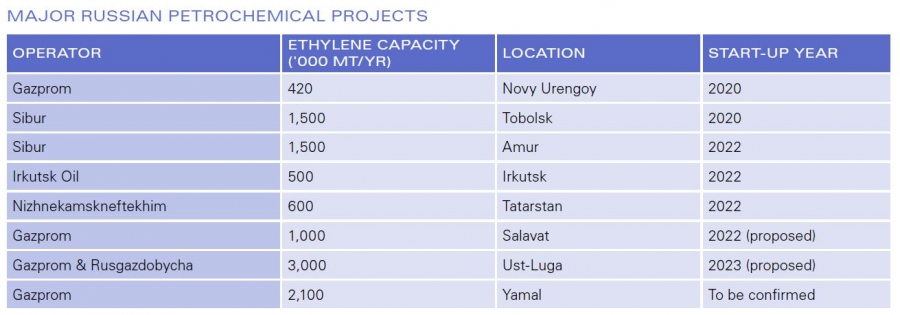

Leading the charge is Sibur, Russia’s top petrochemicals producer, which is commissioning the $9.5bn ZapSibNefteKhim (west Siberian petchems) complex in Tobolsk, Western Siberia. At its peak, the complex will turn out 1.5mn mt/yr of ethylene, adding to Russia’s 3mn mt/yr of existing supply, along with 500,000 mt/yr of propylene, using ethane and other feedstocks. The ethylene and propylene will be used to produce 1.5mn mt/yr of polyethylene and 500,000 mt/yr of polypropylene.

ZapSibNefteKhim will launch commercial production in phases during this year, under the current plan. But the timing will depend on the market outlook, which is unpredictable, to say the least. Economies across the world are entering recession as a result of efforts to slow the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. This has devastated demand for petrochemicals, save for a few bright spots such as products used to manufacture personal protective equipment.

While Sibur is by far the biggest player in Russian petrochemicals, upstream-focused companies are also entering the fray. According to local press reports, state gas giant Gazprom has drawn up plans for a major gas-based petrochemicals base on the Yamal Peninsula, home to some of its largest gas fields.

The Yamal complex is expected to process up to 40bn m3/yr of gas from Bovanenkovskoye, and produce 37.8bn m3 of purified methane, 2.3mn mt of ethane and 0.8mn mt of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) annually. The ethane and LPG will then be used to produce 2.1mn mt/yr of polyethylene.

Gazprom is seeking $9.9bn of debt financing to pay around 70% of the project’s cost and is looking to secure partners to cover the remaining sum. While Gazprom is committed to realising the plan, a final investment decision (FID) is still some way off.

There will be plenty of spare ethane to go around on Yamal, with Bovanenkovskoye working up to its third-phase capacity of 115bn m3/yr. Gazprom intends to launch the first stage of the neighbouring Kharasaveyskoye field in 2023, adding another 32bn m3/yr of supply.

Gazprom is developing a similar largescale gas processing hub on the Baltic Sea, alongside private partner Rusgazdobycha. Ethane from the plant will be delivered to a petrochemical plant Rusgazdobycha is building nearby, to produce 3mn mt/yr of polymers. First production is expected in 2023.

Other sanctioned projects include a 420,000 mt/yr ethylene plant in Novy Urengoy that Gazprom aims to start up this year. Chemicals group Nizhnekamskneftekhim and eastern Siberian producer Irkutsk Oil (INK) also plan to commission ethylene plants with capacities of 600,000 mt/yr and 500,000 mt/yr respectively in 2022.

For an oil producer such as INK, going down the petrochemicals route helps maximise value from the marginal amount of gas it produces, before it sells the gas cheaply to Gazprom. Gas demand in eastern Siberia is limited and Gazprom has exclusive rights to export pipeline gas, which it does through the Power of Siberia (PoS) pipeline to China.

Elsewhere, Russia’s top private oil producer Lukoil is working to expand its petrochemicals capacity in Russia’s southern province of Stavropol, to maximise value from its Caspian Sea gas production.

Sibur also has a pre-sanction project to produce 1.5mn mt/yr of ethylene in the Amur region by 2022, using ethane extracted from gas on route to China via PoS. That same year Gazprom intends to bring a 1mn mt/yr facility on stream in Salavat, Bashkortostan.

Uncertain times

In an age of unprecedented demand uncertainty, Russian oil and gas companies are scrambling to add value to what they produce.

Abroad, their main target is customers in the Asia-Pacific region. But some of the projects underway, especially those in western Russia, will also cater for the domestic market for certain petrochemical goods. ZapSibNefteKhim, for instance, is due to sell as much as 40% of its products in Russia, with the rest exported.

Russia’s government is eager to see the sector thrive: it will help it diversify and strengthen its revenue base and to substitute imports. In March last year it unveiled a roadmap strategy with the aim of encouraging $40bn in petrochemicals investments and creating some 18,000 jobs by 2025.

The strategy outlines a package of support measures. Chief among them is the introduction of a reverse excise duty for ethane that would effectively subsidise the commodity’s domestic use. The subsidy will come into force in 2022 and amount to rubles 9,000 ($117)/mt.

While Russia’s ministries of energy and finance have agreed on the terms of the subsidy, they are still at odds over how to fund it. Moscow is now facing difficult budgetary decisions following the oil price collapse, making finalising the scheme all the harder.

Russia also has a penchant for altering policies after investments have been based on them, adding to the uncertainty. The government also introduced a zero rate of mineral extraction tax for gas-based petrochemical projects last month.

Advancing its petrochemicals industry is a sound long-term strategy for a country like Russia that is well endowed with oil and gas resources. The problem is that many other major oil and gas producers are following a similar course, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the US majors such as ExxonMobil. Even before the Covid-19 crisis took hold, global petrochemical margins were squeezed by weak economic growth and rising supply. Russia may therefore struggle to find its place in the market, even with the competitive edge that its resources provide.