Russia Reactivates ‘Yamal-2’: A Real Project or Just Another Bluff?

On 3 April, President Vladimir Putin instructed Gazprom’s president Aleksei Miller to consider a plan for the Russian company to build ‘a second line for the Yamal pipeline’, in order to increase the transmission capacity to supply Russian gas to Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. A day later in St Petersburg, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the Russian company and EuRoPol Gas (whose shareholders are PGNiG, Gazprom and Gas Trading, a company that deals in the trade of gaseous and liquid fuels; its shareholders include PGNiG and Gazprom Export) to undertake a feasibility study of this project.

The Russian proposal in fact marks a return to the concept of peremychka (intersystem connector), linking Belarus with Slovakia via Poland. Given the situation on the European gas market (a progressive drop in demand for Russian gas, and the oversupply of raw material from other sources), as well as Gazprom’s plans to expand its existing transmission infrastructure, the project makes little economic sense. Its implementation could bring about a rise in gas supplies to Central Europe, which at this time is rather unlikely. In this situation, it seems that the principal and immediate goal of the plan is to increase Russian pressure on Ukraine in connection with Moscow and Kiev’s ongoing gas negotiations, as well as Ukraine’s policy of importing natural gas from the West. It is possible that Russia will use the proposal to build peremychka as a pretext to modify the basis of the South Stream project.

Yamal-2, a.k.a. the peremychka

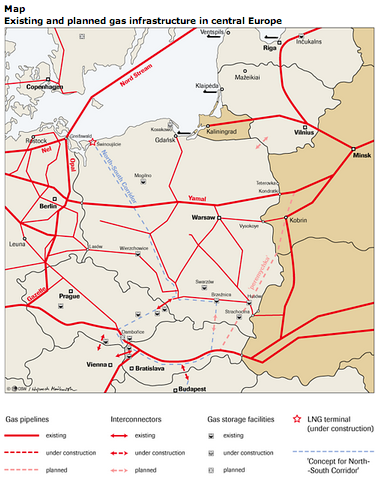

President Putin’s declared intention to return to the ‘second line of the Yamal pipeline’ may indicate that Gazprom should consider implementing the provisions of the Polish-Russian intergovernmental agreement of 1993, which provides for the construction of another Yamal–Europe pipeline (which would cross the territories of Belarus and Russia and transport Russian gas to Germany). In fact, the Russian proposal is an attempt to reactivate a different concept, which first appeared in 2000; this was based on the construction of peremychka (intersystem connectors), leading from Belarus (Kobrin) through Polish territory to Slovakia (Veľké Kapušany), through which Russian gas would be transported to Central European countries avoiding Ukraine. This theory is confirmed by Putin’s indication that Slovakia and Hungary would be the customers for the gas. The memorandum signed on 4 April (whose content has not bee publicly revealed) does not subject the parties to any legally binding obligations. It has been revealed that specifications for the Russian proposal can be expected in the next six months, and the project would possibly start shortly after the completion of the South Stream pipeline, i.e. in 2018-2019.

The declared objectives...

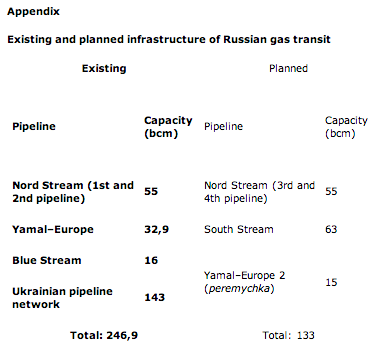

Official statements indicate that Russia’s objective is to increase the transmission capacity (“increasing the security of supply”) to the countries of Central Europe (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary) to at least 15 bcm per year. However, doing so is not justifiable in current economic conditions. This is due to changes on the European market (oversupply of gas, and the ongoing diversification of gas supply sources, including the development of LNG projects), which have contributed to a drop in demand for Russian gas in Europe. In 2012, the export of Russian gas to Europe (including Turkey but excluding the CIS countries) amounted to 138.8 bcm (compared to 150 bcm in 2011). The reduction in Russian gas supplies was also true of Central Europe: for Poland from 10.25 to 9.94 bcm; Slovakia from 5.98 to 4.19 bcm; and Hungary from 6.26 to 5.29 bcm. In addition, current medium- and long-term forecasts foresee that demand for gas will remain static, or increase by only a small amount. The existing pipeline infrastructure can now handle transfers of 246.9 bcm (Nord Stream 55 bcm; Yamal-Europe 32.9 bcm; via Ukraine 143 bcm; Blue Stream 16 bcm), which represents significant oversupply from Russia. If Russia realises all its infrastructure plans (the construction of South Stream, with a target capacity of 63 bcm; the construction of the third and fourth lines of Nord Stream, with a capacity of 27.5 bcm each; and the construction of the peremychka), the capacity of pipelines used to transport natural gas to the European market will rise to 379.9 bcm. At that point, the infrastructure’s capacities will exceed the size of current demand for Russian gas in Europe by more than two and a half times.

...and the real ones

Although this was not directly apparent in President Putin’s statement, it seems that behind the stated objective of improving the transmission capacity lies Russia’s intention to increase gas supplies to the countries of Central Europe, and thus strengthen its position on the regional gas market. This was confirmed by statements which representatives of Gazprom made after the memorandum with EuRoPol Gas was signed. This means that the final decision on the construction of Gazprom’s new pipeline will be taken as long as Poland and other Central European countries express interest in increasing their imports of Russian gas. That, however, seems unlikely.

The construction of such a pipeline via Poland could – although not to such a degree as the Nord Stream and South Stream projects would – lead to a reduction in Ukraine’s importance as a transit country. Thus, the project to build a gas pipeline through Poland is in fact an additional instrument for Russia to put pressure on Ukraine. Moscow’s aim is to force Kiev to cede control over Ukraine’s gas pipeline system to Gazprom, and to maintain Ukraine’s energy dependence on Russia. Gazprom is clearly dissatisfied at Ukraine’s efforts to diversify its gas sources. In March, Naftohaz began importing gas from Hungary (the contracts signed allow for up to 5 bcm of gas to be imported annually), and it has also been buying gas from Germany via Polish territory for several months (based on an agreement with RWE Supply & Trading, which provides for a supply of 1.4 bcm of gas annually). In addition, options to import gas from Slovakia are being considered (up to 10 bcm per year).

While the current amount of raw material Kiev imports from the West is still small (totalling about 150 million m³ in the period from November 2012 to February 2013) – mainly due to the technical limitations of gas imports from Poland and Hungary – implementing the ambitious plans to increase diversification mentioned above is likely to undermine Gazprom’s monopoly position in Ukraine. In addition to the problems that will arise with the implementation of South Stream (the investment costs are estimated to rise to US$38.5 billion, and there is little hope of obtaining exemptions from the provisions of the Third Energy Package), discussions on a new gas pipeline through Polish territory (regardless of whether the pipeline does in fact come into existence) may provide a convenient excuse to modify the project. This would confirm the truth of unofficial reports of emerging doubts in Russian decision-making circles about the profitability of implementing South Stream in its original form. Complete abandonment of the pipeline seems unlikely, however, as Vladimir Putin treats it as a strategic project. Nevertheless, it is still possible that Moscow – especially if it gains control over the Ukrainian gas pipeline network – will revise the project’s original objectives (for example, by reducing the project’s originally planned capacity).

Finally, it is possible that Russia is not in fact so determined to construct the pipeline on Polish territory; that would only increase the capacity of bus transit through Belarus, which is owned by Gazprom. Further, Russian gas could partially be distributed in Central Europe with the use of interconnectors, including a Polish-Slovak one (this project is currently undergoing a feasibility study as part of the EU’s North–South Gas Corridor project). But this is not a realistic prospect without the construction of new pipelines, or the expansion of existing ones, on Polish territory.

Conclusions

In recent weeks, Russia’s actions have suggested that on the one hand, Moscow continues to see energy projects as an instrument to serve its geopolitical objectives. The return to the peremychka concept is a means of putting additional pressure on Ukraine – not only in the context of the ongoing gas negotiations, but also in the context of drawing Kiev into the Russian integration projects of the Customs Union and the Eurasian Economic Union. We should thus expect that after Gazprom’s likely takeover of Ukraine’s gas pipeline network, the plan for transit via Poland will cease to be relevant.

On the other hand, activities in Europe (including the letter of intent signed on 8 April between Gazprom and the Dutch company Gasunie on the development of the Nord Stream gas pipeline) confirm that the European market is still the priority in Russia’s gas strategy, particularly in the context of the problems with plans to expand onto the Asian market: negotiations with the Chinese on price have been difficult; there is a limited supply of outlets for ‘pipeline’ gas; and the LNG project is promising, but is still only in its initial phase.

Szymon Kardaś for the The Centre for Eastern Studies. The Centre for Eastern Studies is a research institution dealing with analyses and forecast studies of the political, social and economic situation in the countries neighbouring Poland and in the Baltic Sea region, the Balkans, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

_f268x103_1366391839.jpg)