Russia struggles to cut flaring [NGW Magazine]

Russia’s campaign to clamp down on flaring and monetise more of its associated petroleum gas (APG) has been slow and grinding. More than a decade after controls were first put in place, the country is still struggling to reach its 95% target for utilisation.

During the Soviet era, APG was considered a waste by-product of oil production rather than a valuable fuel, and this belief persisted well into the 2000s. Faced with international pressure over Russia’s high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the government set out its ambitious 95% goal in 2007 – a time when more than a third of Russian APG was being flared. Moscow gave producers until 2012 to comply.

Utilisation finally reached a record 89% last year, according to data published by the energy ministry, suggesting that compliance is just around the corner. But this achievement needs some context.

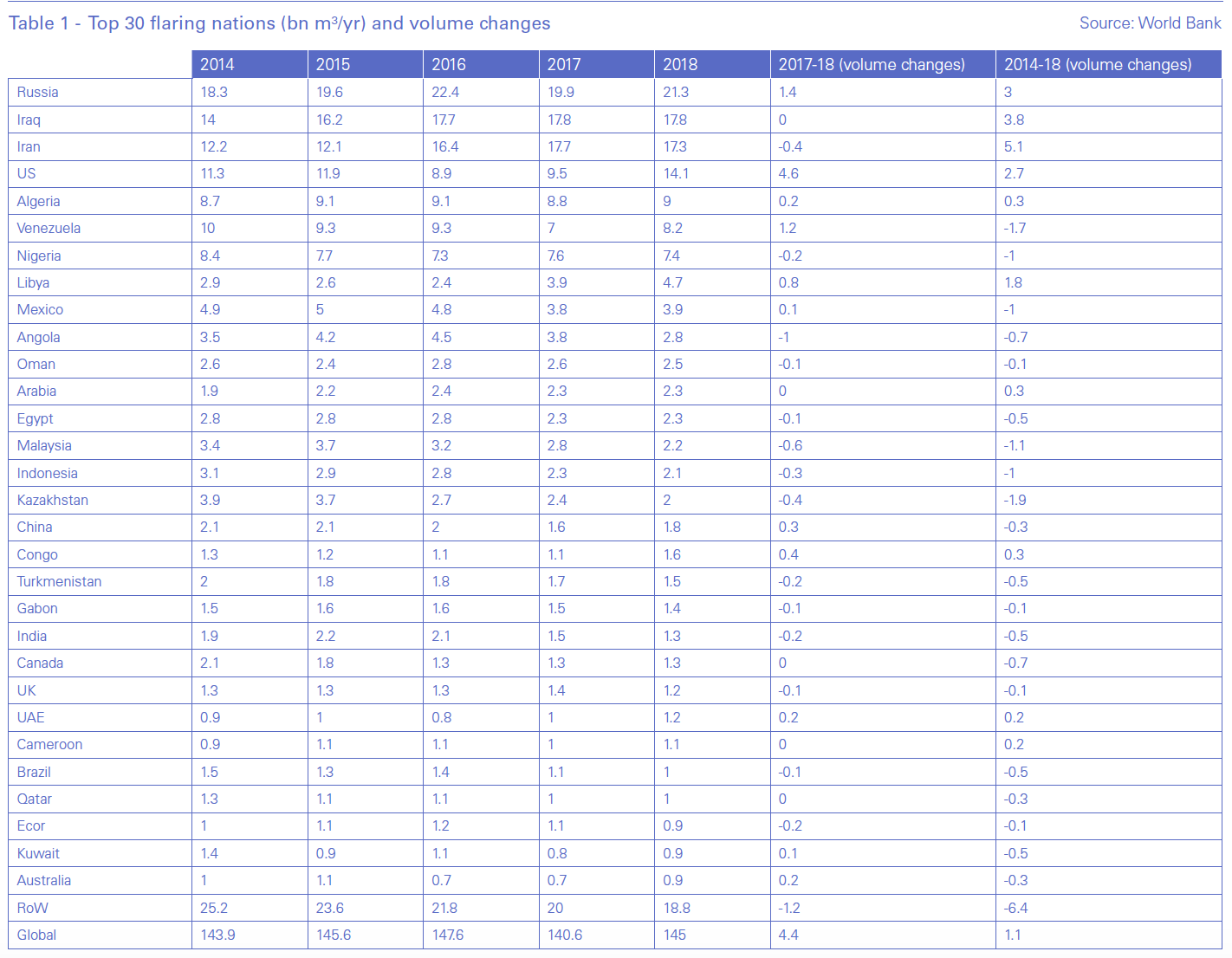

Russia remains the world’s biggest flarer, burning 21.3bn m³ last year alone and accounting for 14.7% of total gas flared, according to the World Bank’s Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR). Some way behind in second and third place were Iraq and Iran which flared 17.8bn m³ and 17.3bn m³ respectively. Indeed, Russia’s utilisation of APG has remained virtually unchanged over the past two years in percentage terms, while the total volume of gas it flared actually rose by 1.4bn m³ in 2018, lifted by rising overall gas production.

Not all Russian producers are at the same stage of tackling the problem. One would suspect the worst offenders to be smaller non-integrated firms lacking the financing and infrastructure to utilise their APG. But the data suggests otherwise, with the larger state concerns trailing behind the national average.

Among the country’s oil majors, the main laggard is Gazprom Neft, the oil arm of state-owned Gazprom. According to its own report, the company utilised just 77.7% of its APG last year. Also considerably behind the curve was government-run Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil producer, which made use of just 84.4% of its associated gas. Privately owned Lukoil proclaims itself the first large Russian oil producer to take the issue of flaring seriously, and this claim is not unmerited, with the firm boasting a utilisation rate of 97.4% in 2018. But in first place is Surgutneftegaz, Russia’s fourth biggest producer, which boasts an extremely high rate of 99.6% that year.

Remote fields

Russia introduced hefty penalties for gas flaring between 2012 and 2014, prompting producers for the first time to invest heavily in cutting their emissions. While these fines still apply, the lack of growth in APG utilisation in recent years suggests they have become a manageable cost that companies are willing to bear, especially as the oil price rises.

The lack of progress can also be explained by Russia’s push to develop increasingly remote oil projects in the Arctic and other areas where gas infrastructure is scarce. Gazprom Neft is a frontrunner in this region, which goes some way in explaining its low level of APG utilisation. Monetising associated gas is a significant challenge at Gazprom Neft’s Messoyakha, Novoportovskoye and Prirazlomnoye oilfields, all of which are inside Russia’s Arctic circle and represent the company’s largest greenfield projects. Their development has been the main factor behind rising flaring by Gazprom Neft since 2016.

Gazprom Neft has come up with some short-term solutions for APG at these sites, so that the issue does not impede its development work. At the Messoyakha project, for instance, the company is looking to transport APG it produces at the West-Messoyakh field to the nearby, undeveloped East-Messoyakh field, where it can be stored for future use.

Longer term, however, Gazprom Neft and other producers will have to invest a lot more money to avoid flaring too much gas. The company is considering an LNG project to make use of gas at the Novoportovskoye field, or alternatively building a 10bn m³/yr pipeline to transport the gas across the Ob Gulf to the Yamburg field, where it can enter Russia’s national pipeline system.

As Russia’s core petroleum basins grow mature, producers are relying increasingly on projects in the Arctic and other remote regions as a means of keeping output stable. As such, APG utilisation is set to become a growing problem in these areas unless Russia develops the infrastructure to transport gas to places where it can be used. This said, the government is unlikely to come down too hard on producers for failing to meet requirements, viewing the development of Arctic oil reserves as a strategic national goal.

Solutions

Countries across the world have devised varying solutions for making use of their APG. The GGFR has advocated the development of small-scale LNG and CNG production, while some countries, including several in central Asia, have looked towards gas-to-liquids (GTL) technology, whereby gas can be converted into gasoline, diesel and LPG. These methods have limited application in Russia, however, where the ample availability and cheap conventional motor fuels puts into question their feasibility.

For Russia, a more suitable solution – at least at projects that produce large quantities of APG – is the petrochemical option. Russia has lagged behind other major oil and gas producers in this segment, accounting for only 1% of global supply. But the government has recently drawn up new measures for spurring investment, with the aim of doubling production to around 20mn metric tons/yr by 2030.

Several new polymer ventures are slated to enter operations in the next few years. The first, due online later this year, is Sibur’s ZapSibNefteKhim plant in Tobolsk, which will run on ethane partly sourced from APG produced across western Siberia to produce 1.5mn mt/yr of ethylene that can be processed further into more valuable polyethylene. Ethane is the preferred choice of feedstock for many of the upcoming projects, given its low cost, which bodes well for APG utilisation.

Related Articles: