The Reality Behind Russia’s Turkish Stream

Last December Moscow took Europe by surprise with an announcement that South Stream, a 63 billion cubic metre (bcm) pipeline designed to bring Russian natural gas to southern Europe across the Black Sea would be scrapped and replaced with a pipeline of similar capacity that would cross Turkey and stop at its border with Greece.

Some energy analysts hailed the new project –Turkish Stream – as a geopolitical asset for Turkey, allowing it not only to source more natural gas at a time when its energy consumption is growing, but also to secure a position of influence in the region, as it would become a key transit route.[1]

Others suggested that Turkey’s partnership in the project that will bring 15.75bcm/year to its domestic market and earmark the remaining 47bcm for European customers would give Ankara a leverage position in its negotiations with Russia.[2]

The reality behind this project disproves the solidity of these arguments and raises serious questions with regards to Turkey’s energy security and that of the surrounding region.

Gas curtailments

It is assumed that Turkey’s decision to participate in Turkish Stream tallies with its ambition to become an energy hub that would be at the heart of multiple transit routes starting in the hydrocarbon-rich countries of the East and heading to the energy markets of the West.

Very few, however, are familiar with the events that preceded the launch of Turkish Stream on 1 December 2015 during the visit of the Russian President Vladimir Putin to Ankara.

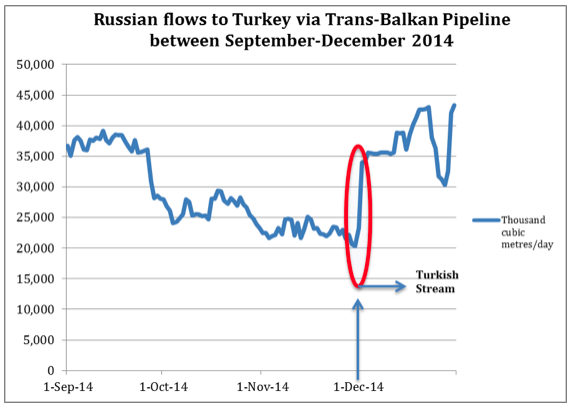

At the end of September 2014, Russia’s Gazprom began to decrease its gas exports to Turkey until critical volumes entering the country through the north-western border point, and feeding the heavily populated Istanbul region, were reduced by half.

Under normal circumstances Turkey receives an average 42 million cubic metres of Russian gas via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline, which transits eastern Ukraine and heads south via Romania and Bulgaria.

However, by the last day of November, imports had dropped to 20.3mcm/day, having induced confusion and panic among Turkey’s government and private natural gas companies who feared extensive blackouts this winter. These fears were entirely justified.

Although nearly two-thirds of Turkey’s energy consumption is concentrated in the north-western Marmara region, the area is heavily dependent on Russian gas shipped via the Trans-Balkan pipeline.

Additional sources come from Turkey’s sole storage facility located in this area and two receiving terminals for liquefied natural gas (LNG). These sources complement the Russian pipeline volumes, but are not sufficient to replace them in case of Russian curtailments.

On the other hand, Turkey’s additional gas imports from Iran and Azerbaijan, as well as from Russia via the Blue Stream pipeline, which crosses the Black Sea and lands in central Anatolia, cannot move easily from east to west because of technical constraints in the transmission system.

In a nutshell, without Russian gas via the Trans-Balkan pipeline to the north-western region, Turkey’s energy security and, implicitly, its economy are at risk.

When Russian volumes started to drop dramatically in October and November, the Turkish government and private energy companies feared that Turkey was heading towards a crisis, particularly as winter was approaching and there were not enough supplies to cover peak demand.

Despite indications that the government had gone to great lengths to devise backup plans - including purchasing more LNG than last year, ramping up hydro production to compensate for expected drops in thermal generation, storing more gas – they could only do as much as the technical limits of the system allowed.

By the 1st December 2015 when Vladimir Putin arrived in Ankara, Turkey’s private and public gas companies were already on high alert.

However, within less than two days of Mr Putin’s visit to Turkey and Ankara’s decision to partner up in the Turkish Stream project, Russian exports to the Marmara region increased by 13mcm/day and by mid-December they reached their normal daily average of 42mcm/day.

The Turkish transmission system operator BOTAS does not publish entry and exit points for gas imports, but relevant data related to the Russian gas flows via the Trans-Balkan pipeline entering Turkey at the Bulgarian-Turkish Malkoclar point are available on the website of the Bulgarian TSO Bulgartransgaz as illustrated in the graph below.

Source: Bulgartransgaz, http://www.bulgartransgaz.bg/en/pages/istoricheski-danni-45.html Daily flows for 2014, Column E, Malkoclar exit point

Russia and Gazprom, the company exporting the gas, never gave any official explanations for the two-month gas curtailment to Turkey or for the return to normal flows following the Turkish Stream announcement.

Turks themselves had feared that the reduction in exports was caused by the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine, which the Russian gas transits before reaching Turkey.

However, with the benefit of hindsight there are reasons to believe that the Turkish government may have been under pressure to sign up to Turkish Stream.

This is because they were confronted with a tough dilemma: either reject the project and face major energy shutdowns this winter, or accept it and thus avoid a crisis in an electoral year.

The question is pertinent especially if considering that the method used by Russia in this case is similar to methods used against other European countries and which are ‘choreographed to surprise, confuse and wear down the opponent”.[3]

New concerns

Now that Ankara has been won over and Turkish Stream is publicly described as a solution to Turkey’s growing energy demand and a boost to its regional power ambitions, there are new concerns looming on the horizon.

Firstly, the project aims to completely redesign the energy supply landscape in Turkey and Eastern Europe. The Russian volumes that are currently transported via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline through Ukraine to Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey will be re-routed so that Turkey will become the first rather than the last recipient of gas in the supply chain.

This in itself would be beneficial to Turkey as its security of supply would no longer be vulnerable to Russia’s political stand-offs with Ukraine or other eastern European countries along the route. Or so the theory goes.

However, the experience of the two months at the end of last year when Russia halved its supplies of gas to Turkey proves that a country’s position along the supply route is irrelevant as long as Moscow wishes to extract concessions from various partners.

Secondly, Turkish Stream, which will be made up of four threads is expected to bring 15.75bcm/year to Turkey as part of a first thread to be completed by the end of December 2016. This will be only 1.75bcm/year more than what Turkey currently gets via the existing Trans-Balkan Pipeline. In that form the new project will hardly bring any additional value to Turkey.

Thirdly, Russia has reserved the right to build the 660km offshore section across the Black Sea and said it would partner up with the Turkish incumbent BOTAS in building the 180km onshore section inside Turkey up to the Greek border. Such a proposal should raise alarm bells inside the Turkish government, as Russia may gain access to a critical piece of infrastructure in Turkey’s most populous area. Gazprom has already expressed an intention to buy Istanbul’s gas distribution network, IGDAS, which serves five million customers and has a 5bcm/year capacity. [4]

Fourthly, by placing 47bcm/year of natural gas at Turkey’s Greek border, Russia might render Turkey’s own energy hub ambitions meaningless. These volumes will be more than double the quantities Turkey could transit to Europe from the Middle East and the Caspian region by the end of the decade.

Furthermore, there are significant questions regarding the future of the Southern Gas Corridor, an EU-backed project designed to diversify away from Russian supplies. A total of 16bcm/year are planned to be shipped from Azerbaijan’s offshore Shah Deniz II to Turkey and further west to Greece, Albania and Italy.

The 10bcm/year that are earmarked for southern Europe will also be placed at the Turkish-Greek border at the same exit point chosen for Turkish Stream. This will create significant bottlenecks inside the Turkish and Greek system that will require proportionate investments. Who will pay for these?

Implications for national and regional security

Commercial concerns aside, however, the biggest fears relate to Turkey’s growing dependence on Russia and its implications for its national and regional security.

The argument that Turkish Stream will give Ankara greater leverage in its negotiations with Moscow is being refuted just as we speak.

Turkey’s public and private gas companies discuss their price of natural gas imports with Gazprom on a regular basis. Negotiations are typically conducted in the first weeks of each year and counterparties agree on a new price by the end of January.

This year, Gazprom and its Turkish counterparts have failed to reach an agreement and any further delays could wipe out Turkey’s budding private gas sector.

The complications are related to the indexation of Turkey’s imported gas prices to the price of oil. Since the price of Brent crude has dropped more than 50% within less than a year, Russia argues that the gas price will go down anyway in line with cheaper oil prices and therefore there is no reason to grant a discount higher than 10.25% on offer.

On the other hand, Gazprom has been delaying granting a discount to the private sector, which sources its gas mostly from Russia and holds 25% of Turkey’s total gas imports. Last year, Gazprom agreed to a fixed price that included a 10% discount for the 2014 offtakes that would be offset by a 10% increase in the 2015 price. [5]

Negotiations with BOTAS and the private sector are linked and any decision affecting one will affect the other.

Securing a discount for Turkey’s private sector is absolutely vital because the price that Gazprom insists on for this year would be around $70.00/1000 cubic metres (tcm) higher than the regulated tariff that private companies normally negotiate their prices to customers.

There is an absolute need for Turkey to ensure cheaper energy prices so that its economy can compete with European countries which pay much less for their raw energy.

However the examples just quoted show that despite arguments that Turkey’s partnership in Turkish Stream should give it greater leverage over Russia, Moscow refuses to grant concessions.

Sources active in the Turkish gas market say Russia fears any possible losses incurred as a result of discounts to Turkey because it expects the price of oil to increase in the upcoming months.

The information cannot be substantiated with Gazprom, but it is logical to assume that Russia will do everything in its power to tighten its grip on Turkey, its second largest market after Germany.

Moscow is losing ground in most Europe countries which have to a certain extent implemented a number of policies designed to reduce Russia’s monopoly on imports and infrastructure and to diversify its sources of supply.

With its European customer base dwindling and confronted with plummeting oil prices, Russia may seek to squeeze as much profit from Turkey as possible.

Turkey, which has neither imposed sanctions against Russia in the aftermath of the Ukraine conflict, nor introduced policies to rein in Russia’s influence, will be a natural magnet to Moscow.

Russia is already building Turkey’s first 4.8GW nuclear power plant. Gazprom is the majority shareholder in one of its largest private gas importers and now plans to buy out the shares of another large private gas importer.

It has expressed an intention to snap up the largest gas distribution network of the country and could, in the future, purchase more gas-fired electricity generation.

Such extensive asset purchases will give it a significant position in Turkey as well as allow it to take advantage of Turkey’s crucial geostrategic position, using it as a springboard to the Middle East, the Caspian region and Eastern Europe.

Karen Strumond, The Washington Review of Turkish & Eurasian Affairs, February 2015

[1] “Turkey becomes a powerful player due to Russian gas”, http://vestnikkavkaza.net/articles/politics/65773.html (last accessed 14 February 2015)

[2] “Does the cancellation of South Stream signal a fundamental reorientation of Russian gas exports?”http://www.oxfordenergy.org/2015/01/cancellation-south-stream-signal-fundamental-reorientation-russian-gas-export-policy/ (last accessed 21 January 2015)

[3] “From cold war to hot war”, http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21643220-russias-aggression-ukraine-part-broader-and-more-dangerous-confrontation (last accessed 14 February 2015)

[4] “Gazprom, Marubeni, Turkish firms eye Istanbul gas grid sales – sources”http://af.reuters.com/article/energyOilNews/idAFL6N0ST35M20141104 (last ccessed 14 February 2015)

[5] The information was sourced during interviews by the author with companies active in the Turkish gas sector.

[6] “Russia says South Stream project is over” http://www.euractiv.com/sections/global-europe/russia-says-south-stream-project-over-310491 (last accessed 14 February 2015)