Shale consolidation in full swing [Gas in Transition]

The US shale industry continues to consolidate, with numerous major mergers and acquisitions (M&As) announced since the second half of 2020. Among them is a number of large gas-focused deals, which illustrate that interest in building scale and acquiring new acreage is not limited to the Permian Basin alone.

This marks a significant point in the evolution of the shale industry. When the current wave of consolidation comes to an end, the industry – initially characterised by the presence of high numbers of small independents – is expected to comprise fewer, larger players.

This, in turn, is anticipated to help the industry stay disciplined even if commodity prices rise. This is primarily a concern for oil producers, who will not want oil prices to weaken because of oversupply again, but shale gas drillers also find themselves under more pressure to act with restraint than ever before.

Gas deals

According to data analytics firm Enverus’ senior M&A analyst, Andrew Dittmar, there has been over $30bn worth of transactions in US upstream in the second quarter of 2021, with seven of the deals worth over $1bn.

“This is the most active M&A market we have seen since the second half of 2018,” he tells NGW.

In regions such as the Permian, the M&A deals being struck involve both oil and gas operations. However, some of the recent deals to be announced are purely gas-focused, and these transactions showcase the growing dominance of certain major producers.

Among the major buyers on the gas side recently are EQT and Southwestern Energy. In May, EQT – the US’ largest gas producer – said it had agreed to acquire Alta Resources Development for around $2.93bn in cash and stock. This came shortly after EQT bought Chevron’s assets in the Appalachia region, which holds the Marcellus and Utica gas plays, for $735mn. EQT also reportedly approached fellow Appalachian producer CNX Resources with a takeover proposal in October 2020, but nothing came of this.

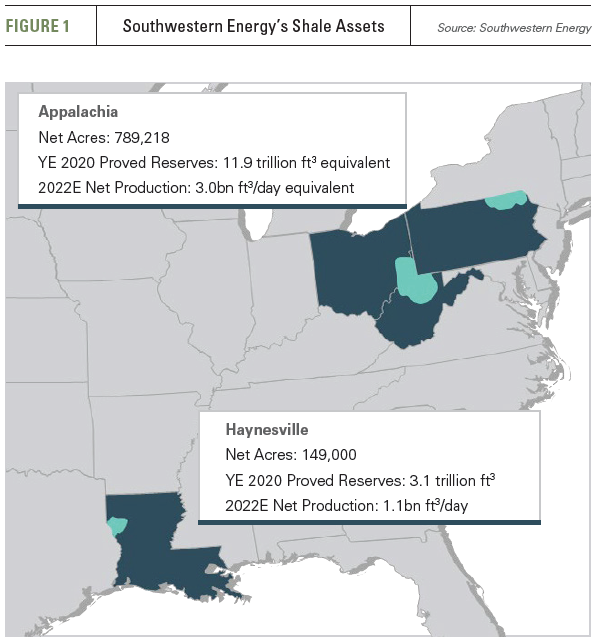

Southwestern, meanwhile, acquired Montage Resources in late 2020 to create the third-largest Appalachian producer. It is now following this up with its newly announced acquisition of Haynesville shale player Indigo Natural Resources for $2.7bn. The transaction is notable because while some producers are using M&As to build scale in a single core region, Southwestern is expanding its operations (Figure 1) into a new play.

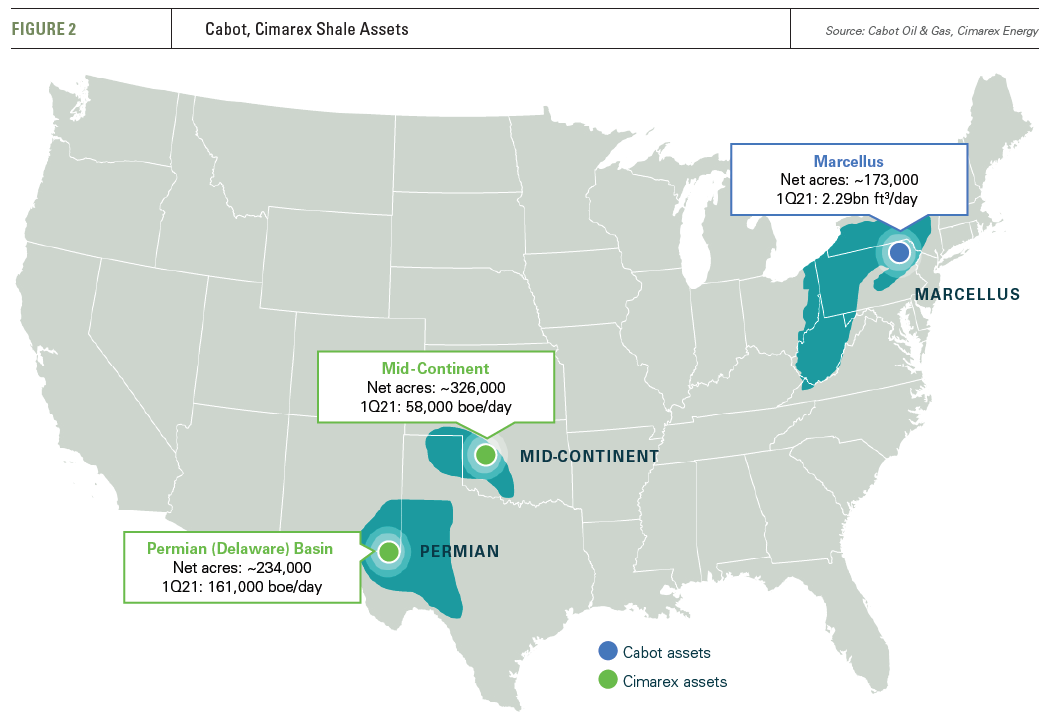

Southwestern is not the only one to be entering a new region. Perhaps more surprisingly, Appalachia-focused Cabot Oil & Gas and Permian player Cimarex Energy agreed in late May to a merger worth $7.4bn. This deal will shift Cimarex’s commodity mix from 42% gas to 79%. Cimarex’s chairman, president and CEO, Thomas Jorden, has talked this up as a move that will make the combined company more resilient to commodity price cycles.

“Geographical diversification (Figure 2) can bring the benefit of not over-relying on market conditions in a single area, but there is the risk that fragmentation could lead to a loss of focus on the overall company strategy,” oil and gas data firm Evaluate Energy’s senior M&A analyst, Eoin Coyne, tells NGW. He added that companies expanding into different regions would still be benefiting from scale, though.

“Geographical diversification (Figure 2) can bring the benefit of not over-relying on market conditions in a single area, but there is the risk that fragmentation could lead to a loss of focus on the overall company strategy,” oil and gas data firm Evaluate Energy’s senior M&A analyst, Eoin Coyne, tells NGW. He added that companies expanding into different regions would still be benefiting from scale, though.

“Their increased size will lead to better access to capital and therefore borrowing costs,” he says. “They will also gain minor operational synergies, but these will be far less than had they acquired acreage from within their existing core operating areas.”

This could illustrate why many of the M&As over the past year have been focused on a single basin. There can be certain constraints to that approach too, though.

“In general, investors have preferred single-basin companies over the last few years,” says Dittmar. “That is a simpler story to tell and comes with the ability to run a lower cost structure. When it comes to M&A, expanding in-basin provides operational synergies and retains a company's core focus and competency,” he continued. “The exception may be when growth opportunities look limited in a company's home play. That may be the case in Appalachia where infrastructure constraints are a roadblock to growing volumes. That (plus in Cabot's case a shorter inventory runway) encouraged Cabot and Southwestern to look elsewhere for deals,” he says.

Dittmar added that of the two deals, Southwestern's expansion into the Haynesville “looks like a bit more logical of a step out for a gas producer than Cabot's transformation into a diversified Permian and Marcellus producer.”

More to come?

The consolidation wave does not appear to be over yet, though how long it continues depends on factors including commodity price trends over the remainder of the year.

“I think as long as commodity prices hold at current levels or better, there is still significant room to run in this market. On the gas side in particular, there are sensible potential combinations in Appalachia to consolidate within the basin,” says Dittmar. “There is also still running room for consolidation in other plays, and we have seen more multi-basin deals recently. That said, I wouldn't be surprised to see the pace of deals slow a bit later in the year just because so many deals will have already transacted.”

Coyne agreed that deal-making activity could slow soon.

“Although there is still some scope for consolidation, I expect the wave will broadly decline and the industry will transition to a normal level of activity during the second half of 2021,” he says. “The majority of the top 20 US gas producing independents have made their moves and it’s likely their focus will now be on integrating their new portfolios rather than making further transformations.”

However, several major companies are yet to make a move, which may yet lead to a few more deals in the coming months, according to Coyne.

Further Haynesville deals also cannot be ruled out, given the play’s proximity to the Gulf Coast, where its gas can serve as feedstock for LNG export plants, among other uses.

“Providing economic inventory in a region with ample infrastructure and close proximity to Gulf Coast markets and particularly LNG export terminals is a key selling point,” says Dittmar. He also believes there is scope for more companies to become comfortable with multi-play deals as the next step in consolidation, if investors become more accepting of these.

Ultimately, whether future deals are focused on a single basin or multiple ones, the end result will be that shale assets will increasingly become concentrated in the hands of a few dominant players, both on the public and private side.

“When the dust settles, the US shale industry will be in the hands of a smaller group of companies that are well placed in terms of stability. I think this will lead to more disciplined strategies, and we are less likely to see over-expansion in production,” says Coyne.

“I think there will be a few main pure-plays per basin and large diversified E&Ps once the current wave of consolidation wraps up,” adds Dittmar. “Consolidated ownership should act as a limiting factor to US production growth, but that will come down to decisions by individual companies since a few big companies can run as many rigs as many small ones,” he says. “The major determining factor there probably won't be the number or size of companies, but how quickly and drastically investors punish a company's stock if they stray from their pledges to focus on capital returns and shift back towards growth.”