Shell’s “death blow” to Cambo an unwelcome precedent? [Gas in Transition]

Shell has dealt what some environmental campaigners have lauded as a “death blow” to the Cambo oil and gas project off the coast of the UK. But the offshore industry warns that the decision, as well as the broader ramifications for the North Sea industry, will result in the UK importing more oil and gas over the coming years, driving up energy bills and, paradoxically, resulting in higher emissions.

Environmental scrutiny

Cambo’s operator Siccar Point Energy estimates the field could yield up to 170mn barrels of oil over its operational life, plus a further 53.5bn ft3 of natural gas, which it notes would be enough supply to power 1.5mn homes for a year. But Shell, which entered the project through a farm-in deal in 2018, said on December 2 it was withdrawing because of poor economics..png)

“After comprehensive screening of the proposed Cambo development, we have concluded the economic case for investment in this project is not strong enough at this time, as well as having the potential for delays,” Shell said.

While Shell said nothing of environmental concerns, it is likely that the sustained campaign against the project by activists over this year played no small part in the major’s decision-making.

“Whilst making a case that it was an economic decision, it does seem more likely to many external observers that Shell has bowed to political and societal pressure, particularly from those who have used the development decision on Cambo as a watershed moment for the debate in the UK North Sea,” Edinburgh-based consultancy Gneiss Energy comments.

Cambo is awaiting approval of an environmental statement submitted by Siccar Point over the summer. Despite the backlash it has faced, the project notably will produce half the amount of CO2 for each barrel than the UK average, according to Siccar Point, and it will not involve any routine flaring or venting. While it will use gas for its power needs initially, it will switch to renewable energy when this becomes feasible, the company says.

Shell is already facing scrutiny over its climate footprint in the Netherlands, where a Dutch court has ordered the company to do more to address its emissions, and activist investors are calling on it to separate its oil and gas business from its activities in renewables and other low-carbon technologies. The company has since moved its tax residency and headquarters to the UK.

Political wrangling

Cambo has also been caught in the middle of political wrangling between the government in Westminster and the government in Holyrood. Shell decided to walk away from the project weeks after Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon expressed her clear opposition.

“I do not think that we can go on extracting new oil and gas forever – that is why we have moved away from the policy of maximum economic recovery – and I do not think that we can continue to give the go-ahead to new oilfields, so I do not think that Cambo should get the green light,” Sturgeon told members of Scotland’s parliament.

The power to block Cambo notably lies with the UK government and not Sturgeon’s administration. But by stating her opposition, she has placed extra pressure on UK prime minister Boris Johnson to deny the project’s approval. For his part, Johnson has avoided taking a strong stance in Cambo’s favour, but in August warned “we can’t just tear up contracts.”

Sturgeon’s words were met with sharp criticism from the oil and gas industry, including veteran ex-Wood CEO Ian Wood, who warned that opposing drilling off the Shetland Islands would be both “counterproductive and damaging,” undermining the UK’s push to net-zero by 2050.

Upstream association OGUK shared this sentiment. Without further oil and gas development, it warns that UK hydrocarbon output could slide by 75% by 2030. The country gets 73% of its total energy from oil and gas, the group’s operations director Katy Heidenreich recently wrote in a commentary shared with NGW. Importing extra oil and gas over the years will be costly, she said, given the nation already spent a net £7bn ($9.25bn) on these overseas supplies in 2020.

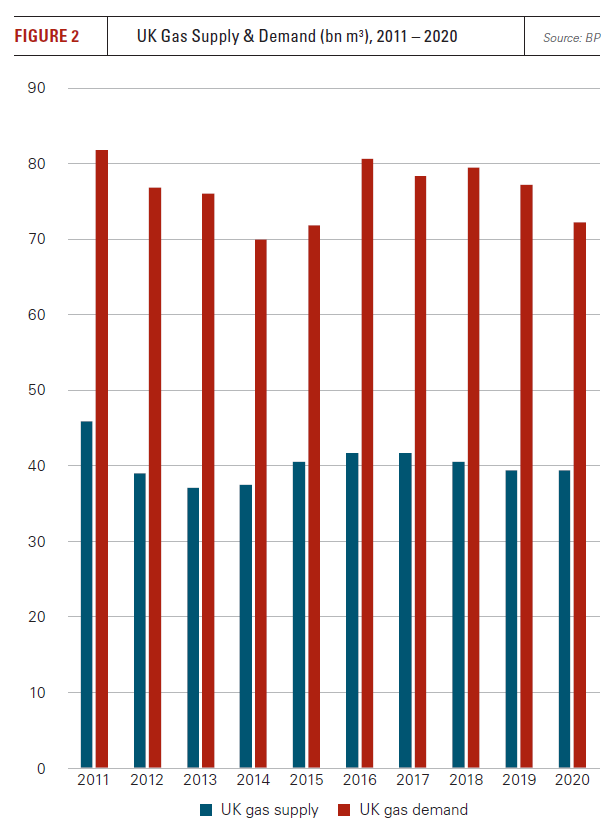

Extra imports

If domestic development grinds to a halt, she says, some 1,600 oil and gas wells will be decommissioned over the next 10 years and the resulting decline in output “would be far sharper than any reduction we could achieve in demand – so imports would surge with householders and businesses facing all the extra resulting costs.”

Shutting down the industry prematurely would also deprive the UK of the skills, expertise and supply chains it needs to deliver the energy transition, OGUK argues, particularly in the area of carbon capture and storage (CCS). As NGW covered in the previous issue of Gas in Transition, the UK government has recently selected two large-scale CCS projects in north England for state funding.

“Shell’s decision to pull out of the Cambo field development is a huge blow, not only for its partners in the project but for the whole of the UK North Sea,” Gneiss says. “Some will celebrate what could be presented as an oil company starting to follow through with its climate pledges, but from a UK perspective, there will be questions about jobs and the climate footprint of non-domestic production. This will be increasingly needed if new projects struggle to get support and may worsen the UK’s overall carbon position.”

Gneiss notes that imported LNG, for example, has five times the carbon intensity of gas produced in the south North Sea. This is partly because the further oil and gas has to travel to market, the more emissions are generated.

Next steps

Siccar Point responded to Shell’s announcement saying it was in talks with the government, stakeholders, contractors and the supply chain to try and find a way forward for Cambo. But on December 10, its CEO Jonathan Roger said work on the project would pause for the time being.

“Following Shell’s announcement last week, we are in a position where the Cambo project cannot progress on the originally planned timescale,” he said. “We are pausing the development while we evaluate next steps.”

Given its past statements, the company will likely need to find another farm-in partner with financial clout like Shell to progress the field. Though with many of the world’s leading oil firms scaling back in the mature and relatively high-cost North Sea, not to mention the heightened environmental scrutiny, this could prove a difficult task.

More broadly, the amount of environmental criticism leveled against Cambo is unprecedented for a conventional, offshore hydrocarbon project in the UK, comparable only to the stiff opposition that hydraulic fracturing has faced onshore. This bodes ill for future developments. While oil is the main target of environmentalists today, they may take similar aim at gas in the future.