South Korea’s new policy [NGW Magazine]

Ever since his election to South Korea’s presidency in May 2017, Moon Jae-in has been advocating green policies, moving away from coal and also nuclear. He initiated preparation of new energy policies in 2017 to put this into effect. But resistance and power shortages during the summer of 2018 brought home some of the challenges facing this policy.

A novelty in South Korea’s energy politics is the readiness of the president to implement ambitious reforms and to support these by involving citizens in consultations to shape future energy policy, with emphasis on safety and the environment. This, however, can be both a strength and a weakness. A strength in terms of ensuring wider buy-in to policies that emerge from this process, but also a weakness in terms of exposing future government energy policy to what happen to be popular politics at any one time.

South Korea is the world’s eleventh largest economy and ninth in terms of total primary energy demand. It is also the third largest importer of LNG with a 13.2% global share in 2017. It is also the world’s sixth largest nuclear energy producer.

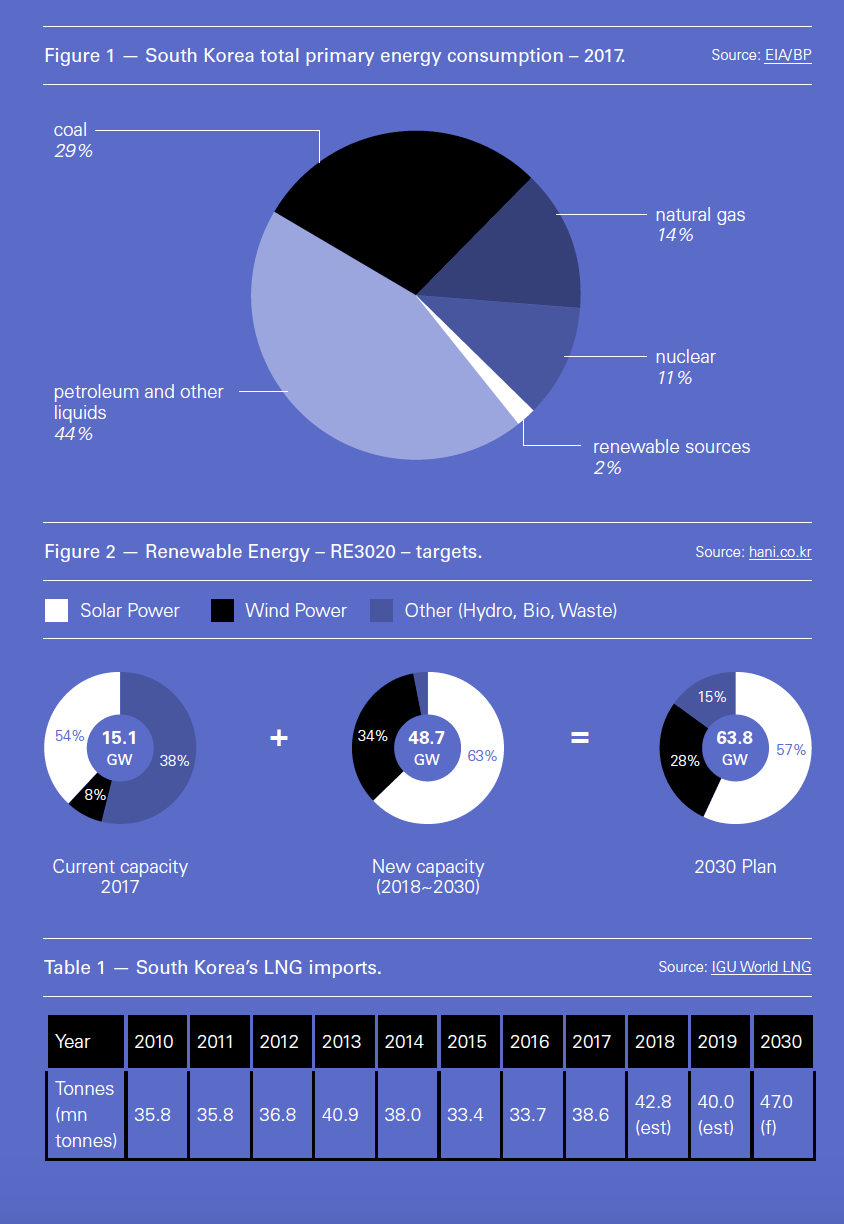

In 2017 its total primary energy consumption was dominated by oil and renewables contributed only 2%.

South Korea’s industries, such as ship building and car manufacturing, are energy-intensive, with imported energy sources meeting almost 98% of its fossil fuel requirements, as the country lacks sufficient natural resources. In 2017 about 54% of the country’s electricity demand came from industry. As a result, having the right energy policies and ensuring the reliable availability of energy at competitive prices is crucial to the country’s future

Nuclear phase-out?

Underlying Moon’s nuclear phase-out policy were public safety concerns, driven by the Fukushima experience and a powerful earthquake that struck Gyeongju on South Korea’s southeast coast in September 2016. This started with discussions to cancel building work on two new nuclear reactors, Shin Kori 5 and 6, at the Kori nuclear plant. Work was suspended in June 2017 when construction was less than a third complete.

But this met with resistance from the builders and local residents. In response to this the government set up an independent ‘citizens’ committee’ comprising 471 Koreans to decide on the project’s future.

After three months of discussions and presentations from experts, stakeholders and interest groups, the committee decided that construction should be resumed. But it also supported the government policy to reduce nuclear energy dependence.

The government adopted these recommendations and incorporated them in its ‘energy transition roadmap’ for the period 2017 to 2030, announced in October 2017. At that time, South Korea had 24 reactors, supplying about 30% of its electricity, with nine more under construction or being planned.

Key provisions of the roadmap are gradual phase-out of coal and nuclear, with eventual decommissioning of all nuclear reactors by 2080. It also includes expansion of renewables to 20% of power generation by 2030.

The roadmap to achieve the renewables target is described in the ‘Renewable Energy 3020 Implementation Plan – RE3020’, released in December 2017. It embraces solar and wind energy to achieve this (Figure 2).

The roadmap to achieve the renewables target is described in the ‘Renewable Energy 3020 Implementation Plan – RE3020’, released in December 2017. It embraces solar and wind energy to achieve this (Figure 2).

In addition, the government is planning to increase the share of renewable power generation to 40% by 2040.

But the nuclear phase-out will be gradual. In fact the number of nuclear reactors will initially increase from 24 to 27 by 2022, before it falls to 18 by 2030. As a result, nuclear energy will still be an important part of South Korea’s energy mix for a long time to come.

New Energy Plan

These provisions were taken up in South Korea’s 8th Basic Plan on Electricity Demand and Supply, which is revised every two years. The 15-year plan was released in December 2017, following a review by a working group consisting of 75 members from government, industries and civic organizations, and approval by the country’s National Assembly. It makes renewables the fuel of choice for power generation for the next 15 years and beyond.

In addition, the country’s National Assembly revised the Electricity Enterprises Act, putting more emphasis on environment and safety issues, ahead of economics.

In 2017 South Korea generated 70% of its power from coal and nuclear and only 6% from renewables. By 2030 the shares will be 36.1% coal, down from 45.3% in 2017, 23.9% nuclear, down from 30.3%, and 20% renewables, up from 6%, with the rest provided mostly by natural gas. This includes boosting the use of LNG in the electricity generation mix to 18.8% by 2030 from about 16.9% in 2017.

Another major objective of this plan is that the government will implement measures to reduce total power demand by 14.5% by 2030, by promoting greater demand-side management and energy efficiency measures.

Clearly, the contribution of coal and nuclear to the country’s power demand will still remain strong even by 2030. These will still be providing 60% of South Korea’s power needs in comparison to 70% in 2017. In reality, the reduction in both coal and nuclear power over this period is modest.

This was the outcome of strong resistance to change by the nuclear industry, fears it could cause energy supply shortages and wider concerns about future impact of the proposed changes on electricity prices. It is estimated that in 2018 gas (LNG) power generation was nearly twice as expensive as nuclear energy.

There is also concern that nuclear phase-out policies could jeopardise the country’s ability to export nuclear technology by denting its credibility in the market. Allowing construction of five nuclear reactors, already in progress, to continue and be completed by 2022 is a way to deal with this problem – for now.

Similarly, the government decided to allow completion of seven coal-fired plants already under construction, for economic and contractual reasons. This means that coal-fired power generation will actually go up by 2022, before it drops to the 2030 target levels. It also means importing more coal in the medium term.

However, these changes and the continued use of nuclear energy will still help bring carbon emissions down by over 26% by 2030, in comparison to 2015.

They will also help reduce air pollution from coal power plants. This is of concern because of high fine-dust particle levels, especially in cities. In order to reduce such emissions, in addition to reducing the share of coal in power generation, state-run utility firms plan to use more low-sulphur coal and upgrade the older facilities.

South Koreans are concerned about air pollution. Last year the government shut down five ageing power plants as part of its policy to reduce coal and improve air quality. But many South Koreans blame China as a contributor to this, pointing out that when pollution levels rose early January, they were highest on Baengnyeongdo Island, 200 km west of Seoul and the South Korean territory that is closest to China.

The government said that the changes it proposes will be introduced gradually, with the biggest coming after 2022. In fact the share of nuclear energy will start declining only after the mid-2020s, under the government’s policy not to renew licences for older nuclear reactors. This gradual shift of energy sources into renewable energy is intended to avoid impairing the current power generation system and to ensure security of energy supply and demand.

Implications for natural gas

Even though there is strong popular support for a substantial increase in renewable energy, support for the expansion of natural gas has not been as strong.

South Korea’s new energy plan allocates a larger role for gas-fired power generation, but it is still more limited than what the gas industry had hoped for and it will be phased in over time. Gas is designed to rise to fill the gap left by nuclear and coal power, and in order to help integration of the planned increase in variable renewable energy. This gap will widen more rapidly from the mid-2020s, in line with the planned decline of nuclear power generation. However, the continuing progress being made in renewable energy storage systems may challenge even this more modest expectation.

In addition to gas for power generation, household and industrial gas demand is expected to grow by over 1.2% annually, underpinning the forecast for increased LNG imports by 2030.

According to the International Gas Union, South Korea imported 38.6mn mt of LNG in 2017. It is estimated that imports in 2018 may reach 42.8mn mt, which would be a record (Table 1). This was due to many nuclear reactors being off-line for maintenance, involving almost half the country’s 24 reactors and causing the nuclear utilisation rate to drop to 63.6%, the lowest ever. This will not be repeated in 2019 and, as more nuclear reactors and coal plants come on line, LNG imports are expected to be lower, nearer 40mn mt this year.

The increase in the use of natural gas by 2030, envisaged in the new plan, is forecast to lead to LNG imports to rise to about 47mn mt.

Even though this will lead to an additional 4.2mn mt LNG imports between 2018 and 2030, an increase of about 9%, it is a relatively small quantity in global terms. It is not sufficient to excite the LNG world. It comprises just over 2% of the forecast increase in the global LNG production between 2018 and 2030.

In fact most of this increase may materialise only after 2025, following the addition of new coal and nuclear capacity. To many this will be seen as disappointing.

However, the coal-gas competition is expected to be altered significantly by adjustments made to fuel consumption taxes, the adoption of an environmental tax and the rising price of CO2 on the Korean emissions market. This is expected to gradually erode the competitiveness of coal against gas and reinforce the role of gas in the future. As a result, LNG may play a bigger role, but not in the short to medium term.

South Korea’s future gas supply is the subject of the 13th Long-term Natural Gas Supply Plan for the period 2018 to 2030, published in April 2018 and covered by NGW. However, even though this confirmed the gas expansion trend, its LNG demand forecast, about 40.5mn mt/yr by 2030, has been criticised as being too conservative.

In order to ensure gas supply security, the plan also seeks to diversify gas supplies and have more flexible LNG contracts that do not include restrictive destination clauses or take-or-pay terms. This favours US LNG. South Korea became the largest importer of US LNG in 2018. But price will be a major factor in the wider use of LNG.

Korea Gas Corp (Kogas), as the world’s second-biggest LNG buyer, plans to pursue such changes as well as lowering LNG import costs. Kogas is also preparing plans to construct South Korea’s fifth LNG import facility, so that it is ready to meet this potential increase in LNG demand. Under its long-term business plan entitled ‘Kogas 2025’, the company is also planning to expand its LNG storage capacity and invest in overseas upstream projects in order to ensure stable gas supplies in future.

Gas pipeline from Russia?

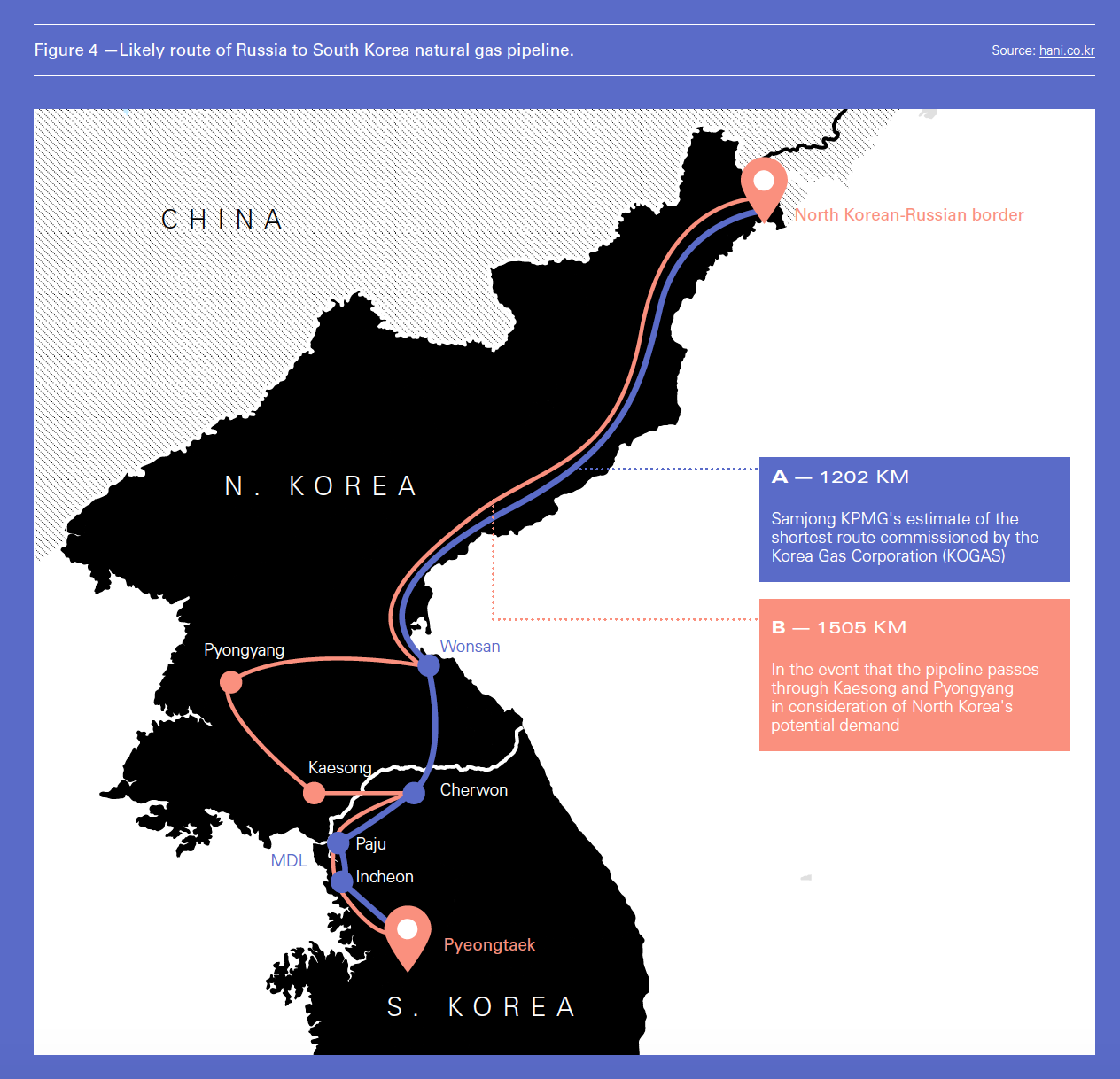

In response to the expected expansion in gas demand, the South Korean government is also exploring the option of importing gas by pipeline from Russia. The two countries are already preparing for a joint feasibility study to construct a 1,200-km natural gas pipeline (PNG) to connect South Korea to Russia’s Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok gas transmission system, running through North Korea (Figure 3).

Moon established a presidential committee on northern economic co-operation in June 2017 that focused on specific projects including PNG and delivering more Russian LNG to South Korea, currently limited to 1.5mn mt/yr, for example through participation by Kogas in Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 project.

Kogas said in October 2018 that it has already undertaken the technical preparations that are one of the preliminary phases for a joint study. However, there is a long way to go.

Apart from everything else there is the matter of sanctions against North Korea, which would needs to be a party to such a project. But given that South Korea may not need additional gas until after 2025, there is time. Kogas said “The PNG joint research is unconnected to sanctions on North Korea, and we are carrying out technical preparations for creating future conditions without violating the sanctions.” Kogaz and Gazprom have already had a number of meetings aimed at launching this study.

Should such a pipeline be eventually constructed, it would impact LNG imports by South Korea.

Challenges

Even though the 20% target for renewables by 2030 is by no means high, achieving it is facing a number of challenges such as land constraints, local opposition and related permit issues.

In order to overcome some of these problems, the government is providing incentives and subsidies for both urban and rural renewable energy installations, as well as providing state loans. But it will also need to reform the power market, seen as being inflexible, so that it can respond to the proposed changes.

There are views that because of these challenges the renewables target may not be achieved, which means that more natural gas may be needed to meet the shortfall.

There are still vocal opponents of rapid nuclear phase-out, fearing its impact on electricity costs and security of energy supplies - questions are being raised as to whether the expected renewable supply will be sufficient to fill the gap - hence the gradual phase-out approach being implemented by the government. Nuclear has long been as a cheap and efficient energy source, promoting South Korea's economic growth.

Some of the challenges in ensuring that stable energy is available at short notice and as needed were brought home during the summer of 2018. The country had to restart two nuclear reactors, which were off line for maintenance work, in order to cope with higher demand for power during a prolonged heat-wave. During the peak power demand, solar and wind power accounted for less than 2% of the total power supply, adding to doubts about whether they can function as main sources of electricity supply.

There is also criticism that the new energy plan is high-cost and low efficiency, requiring more work to make it more feasible. This may still be possible. Following a meeting with a working group composed of experts, civic activists and senior officials, South Korea’s ministry for trade is in the process of finalising the country’s third basic energy plan for the years 2019-2040, which is revised every five years.

Transformation of South Korea’s power systems will be a gradual process. But the levers to effect a shift from nuclear and coal to renewables and gas have now been put in place, with visible results expected over the next decade.