Spain plans to decarbonize [NGW Magazine]

Spain approved late February its very ambitious integrated national energy and climate plan (PNIEC). It was a race against time as the draft was to be submitted to the EU by the end of 2018. But according to Spain’s minister for ecological transition, Teresa Ribera, when she took over in June 2018 there was nothing in place.

Spain also approved a new climate change law and the ‘fair transition’ strategy, to “allow Spain to have a stable, predictable and precise framework for the decarbonisation of its economy by 2050.”

Learning from the problems France is facing, the strategy is intended to alleviate any ill effects that the plan might cause in the regions or sectors of industry most affected by the transition.

The plan sets out ambitious targets for the period 2021 to 2030:

- 21% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as against 1990;

- 42% renewables in the final use of energy;

- 39.6% improvement in energy efficiency; and

- 74% renewable energy in electricity generation.

Spain’s renewables and energy efficiency targets are significantly higher than the corresponding EU targets.

The objective is by 2050:

- to achieve climate neutrality, with a reduction of at least 90% of GHG emissions; and

- to have all electricity generated by renewables.

One consequence of that is that it will close all its nuclear power plants between 2025 and 2035. Spain’s electricity companies have already agreed a scaled closure programme of nuclear plants with the government.

The plan also provides that by 2040 new vehicles will either be electric (EV) or ‘zero emission’ and by 2050 no vehicles will be allowed on the roads that emit CO2. One in six cars is to be electric by 2030.

Ribera claimed that energy modelling carried out to achieve the plan’s objectives has taken into account the foreseeable evolution of the benefits and costs of all different technologies, assuming all are done as efficiently as possible.

This might work for the period to 2030, but any assumptions based on technological breakthroughs beyond that are bound to be subject to considerable uncertainty. As a result, the 2050 objectives are exactly that – it remains to be seen how achievable these will be.

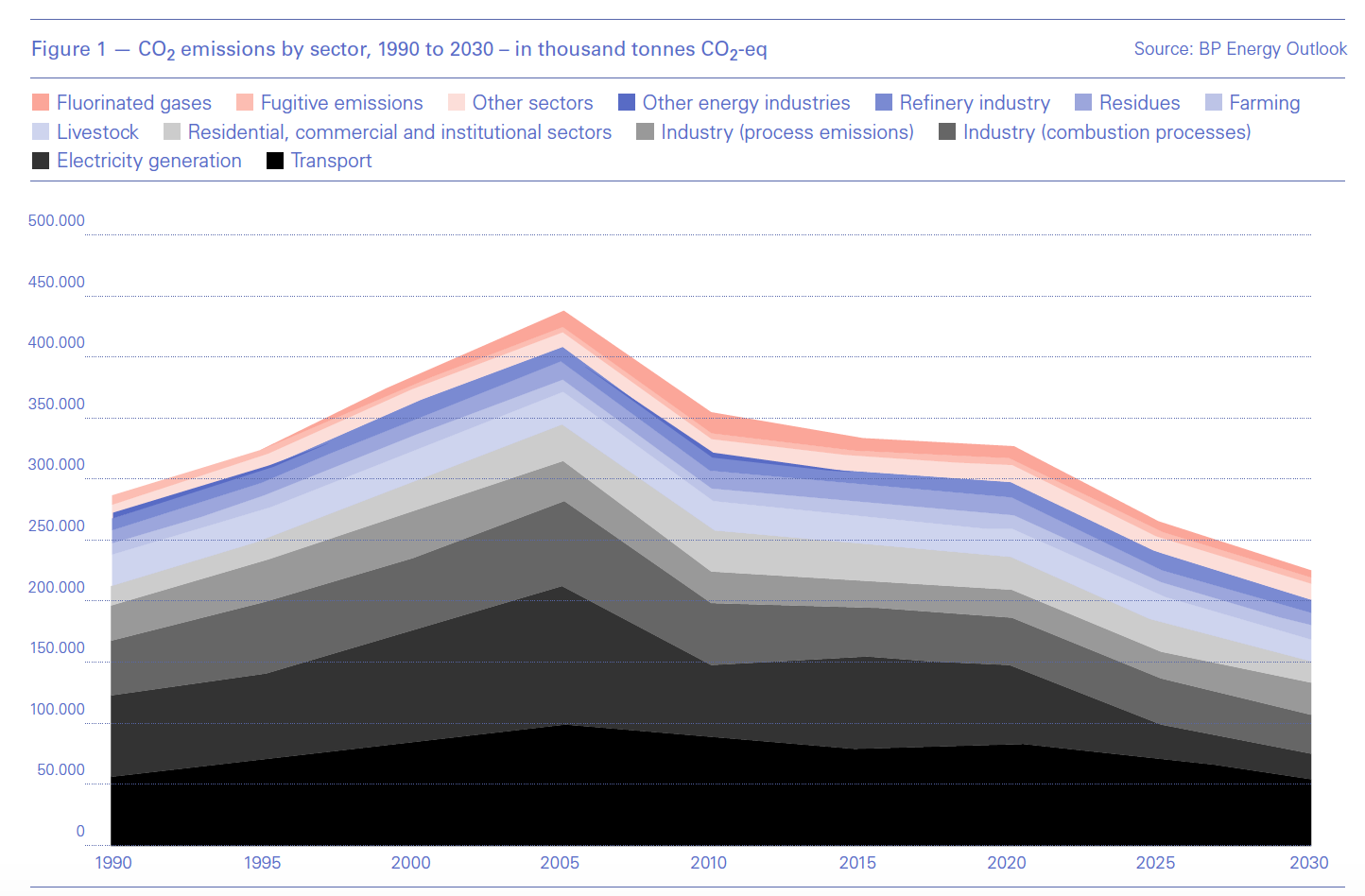

The plan states that since about three-quarters of GHG emissions originate from energy use, decarbonisation is one pillar on which to develop the transition and the other is energy efficiency.

Most reductions of GHG emissions are expected to come from the power generation sector, targeting 44%, and mobility and transport with 28% (Figure 1).

The plan expects that the European Union’s emissions trading scheme will price carbon at €35/metric ton and that advances in energy storage combined with renewables will help phase out coal in power generation. Total storage capacity is expected to reach 6 GW by 2030.

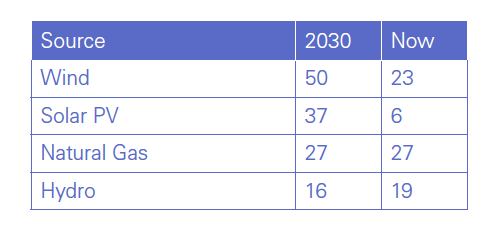

The resulting contribution to total installed power is expected to be 32% wind, 24% solar, 17% natural gas, 10% hydro and the reminder by other energy sources, but not coal.

By 2030 total installed power-generating capacity will be 157 GW, comprising:

In order to achieve this, Spain is committing to installing at least 3 GW of wind and solar power capacity every year in the next 10 years. Expected installed capacity of renewable technologies by 2030 is shown in Figure 2.

The plan aims to achieve a 39.6% improvement in energy efficiency by 2030, leading to a reduction in primary energy use of 1.9%/yr. And this is while GDP increases by 1.7%/yr over the same period. This is equivalent to an improvement in primary energy intensity of 3.6%/year.

Energy security

Given the changes in the energy mix that the plan proposes, there could be important challenges and technological difficulties, which will need to be addressed from an energy security viewpoint:

- Reduction of dependence, especially on the import of fossil fuels;

- Diversification of energy sources and supply;

- Preparation for possible limitations or supply interruptions; and

- More flexibility in the national energy system.

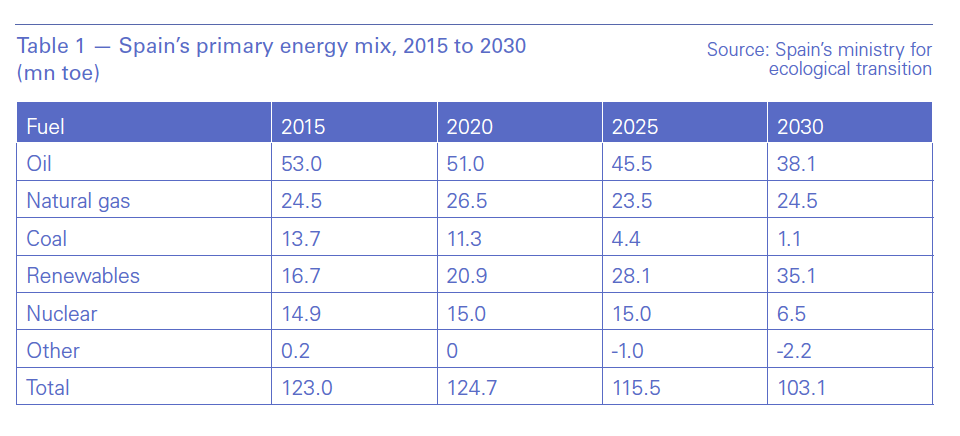

Primary energy demand in 2017 was 123mn toe, of which 99mn toe was from fossil fuels, almost all imported. By 2030 it is expected that the plan will lead to a reduction in primary energy down to 103mn toe, of which fossil fuels will provide 63mn toe (Table 1).

Spain has already closed most of its coal mines. So phasing out coal from its energy mix will not cause any pain. Spain will also stop issuing oil and gas exploration licences, ban hydraulic fracturing, stop drilling completely by 2040; and scrap new fossil fuel subsidies, with existing investments up for review. In addition, a fifth of the state budget will be reserved to have a positive impact on measures that can mitigate climate change.

As a result, renewables and energy efficiency will cut import dependence from 74% in 2017 to 59% in 2030. This will have a very favourable impact on Spain’s trade balance and improve energy security.

Other measures planned to be taken to improve energy security include:

- Increase electrical interconnection, which will contribute to reduce possible negative impacts that are due to supply limitations or interruptions;

- Optimise the use of existing capacity by reducing barriers to exchange of electricity;

- Deepen preparation for contingencies which is already very advanced;

- Adopt the new European regulation on preparedness against risks in the electricity sector; and

- Improve preventative and emergency plans in the supply of electricity, gas and petroleum derivatives.

These will be addressed through developing the National Security Strategy, through the recently-created Committee for Specialised Energy Security.

The degree of interconnection of the Iberian power system with the rest of Europe is inadequate, as its interconnection ratio is less than 5% of the installed generation capacity. By 2020, even with the planned interconnections, Spain will be the only EU country below the target of 10%, so it will be necessary to continue developing new interconnections with Portugal and France.

Through the plan, Spain also intends to promote research, innovation and competitiveness, as well as economic support, for projects in: renewable technology, flexibility of the electrical system, energy storage, carbon capture and storage.

Investments

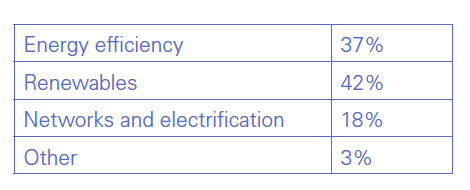

The total investments estimated to be needed between 2021 and 2030 to achieve the objectives of the plan are about €236bn.

The expected distribution of these investments is as follows:

According to the plan, four-fifths of the investment will be made by the private sector and the rest from the public sector.

Important, it is claimed that the plan will generate a rise in GDP between €19bn/yr and €25bn/yr – equivalent to 1.8% of GDP in 2030. This positive impact comes from the economic boost expected to be generated by investments in renewables, savings and efficiency improvements and a reduction in the country's energy bill.

The plan is also expected to lead to the creation of an additional 250,000 to 364,000 jobs by 2030. It also pays special attention to the alleviation of energy poverty.

There will also be benefits to Spain’s trade balance, owing to cumulative savings from reduced imports of fossil fuels between 2021 and 2030, estimated to be about €75bn.

Natural gas

In 2017 60% of Spain’s natural gas imports were through gas pipelines, compared with 40% as LNG.

The most important import gas pipelines are the Maghreb (Maghreb-Europe), the Medgaz (Algeria-Almeria) and the interconnections with France and Portugal.

The breakdown by country of origin of imports of natural gas in 2017 was as follows (%):

Even though Spain considers import of natural gas from Algeria as a possible risk, this is offset by the large volume of LNG imports from a wide range of countries of origin. As a result, Spain has one of the highest levels of diversification of suppliers of gas in Europe.

As can be seen from Table 1, Spain’s natural gas demand is expected to remain more or less steady over the period covered by the plan (2021-30), at about 24.5mn toe/yr – providing close to 24% of total primary energy in 2030 – even though total primary energy demand is expected to decline by 17% over this period. As a result, along with renewables, natural gas is expected to gain in importance.

In order to ensure secure and flexible supplies of natural gas, the plan proposes to integrate Spain’s gas market as follows:

- Establishment of the logistic model of regasification plants to maximise flexibility of the system by allowing the purchase and sale of LNG without distinction of plant in which it arrives physically;

- Implementation of measures to promote liquidity; and

- Exploitation of the storage capacity of LNG plants, as well as their regasification capacity, in order to create physical hubs for both natural gas and renewable gas or hydrogen.

However, citing European energy policy objectives, “with a special regard to the European strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” the energy regulators of Spain and France rejected in January an investment request to build the central section of the planned Midi-Catalonia gas pipeline linking the two countries. This could spell the end of the entire project, especially since the regulators concluded that the pipeline “fails to comply with market needs,” perhaps reflecting Spain’s already high level of gas supply diversification.

Implications

The plan has been welcomed by Spain’s largest utility, one of the world’s largest renewable energy producers. Iberdrola CEO Ignacio Galan said: “It is a breath of fresh air… For almost 20 years, this country has been living without an energy plan.”

No doubt this was in response to the priority that the plan places on renewables, unlocking significant opportunities for investments in clean power in the country. The plan is also providing much needed clarity regarding future use of renewables, lacking in the past.

Ribera said: "The plan is in line with the 2016 Paris Agreement on climate change, and will have positive effects in rural areas, on the environment and in matters of health and social justice." The plan will now begin a period of public information.

However, given that Spain’s greenhouse gas emissions are about 17% above 1990 levels, and the plan requires these to be reduced by 21% below 1990 levels, the actual cut is 38% – a more challenging proposition.

The challenge to the plan is that Spain will be holding a new general election in April, with no real clarity as to who will be forming the next government and how the plan will be implemented.