Spain’s entanglement in Morocco-Algeria dispute highlights the limits of European gas integration [Gas in Transition]

The EU has gone to considerable lengths to integrate the energy markets of its 27 member states, and its efforts have had no small measure of success.

With respect to natural gas, for example, the EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) noted in a report released in mid-July of 2021 that the process of integration was well advanced within the union. “Markets representing three quarters of EU gas consumption are assessed today as well functioning and sufficiently integrated,” it wrote. “Other jurisdictions with some of the historically less developed hubs are also showing promising signs of progress.”

This is an impressive achievement, considering the amount of gas involved. Altogether, the EU’s 27 member-states consume more than 400bn m3/year of gas.

Nevertheless, integration is not the same thing as invulnerability. Since the release of the ACER report, the EU has begun experiencing a gas supply crisis. The two most obvious reasons for the crunch are the resurgence in global demand for gas, which plummeted last year as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, and moves by Russia, the EU’s largest outside supplier of gas, to limit deliveries.

These developments are affecting every part of the EU, not least because of the success of integration measures. In some EU member states, however, there are regional factors in play that make the supply challenges even more complicated.

Another source of supply pressure

Consider, for example, the case of Spain.

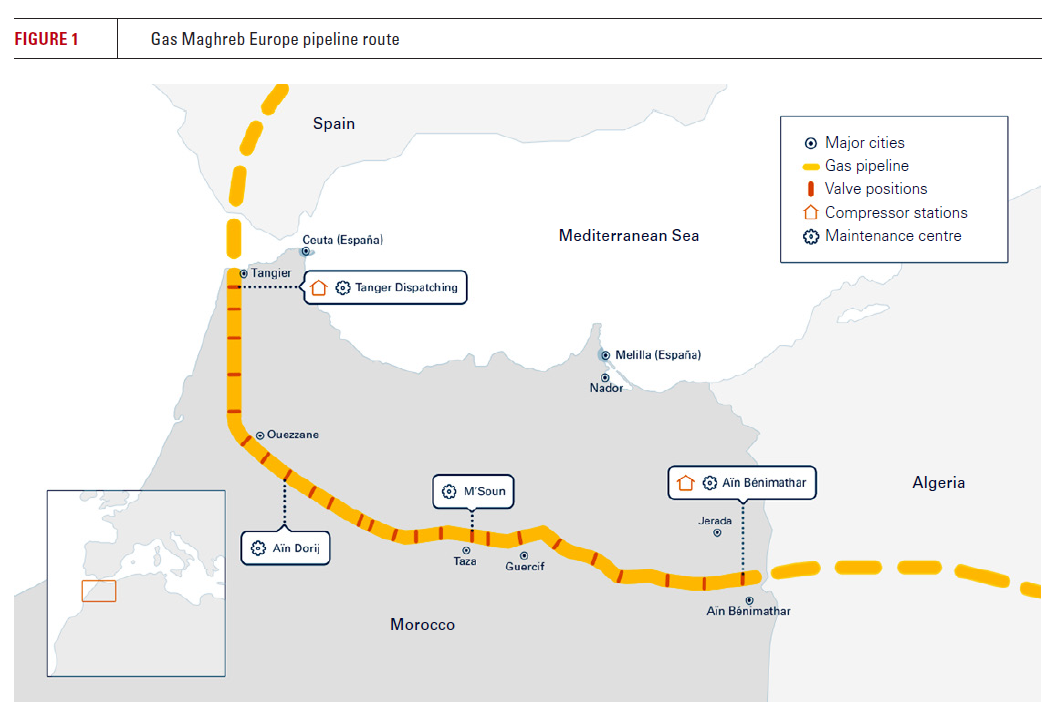

At first glance, the country seems relatively less vulnerable to Russian supply restrictions than many other EU countries. It does import some gas from Russia in the form of LNG, but its largest foreign supplier is Algeria, which delivers gas via two subsea pipelines across the Mediterranean – the 12bn m3/yr Gas Maghreb Europe (GME) link and the 8bn m3/yr Medgaz link. Both pipes originate at Hassi R’Mel, a gas field in Algeria’s Laghouat province. GME passes through Moroccan territory on its way to Spain, where it makes landfall near Gibraltar. Medgaz, meanwhile, passes only through Algerian territory and includes a longer underwater section that runs from Beni Saf to Almeria.

This year, unfortunately, Spain’s dependence on Algeria became a source of concern right around the same time that the rest of the EU began growing concerned about Russian gas deliveries. In August, Algeria cut off diplomatic relations with its western neighbor Morocco. Shortly thereafter, it indicated that this decision would have economic consequences – namely, the refusal to renew an agreement with Morocco on gas transit shipments through GME. (That agreement was due to expire on October 31, 2021.)

Diplomatic maneuvers

Algeria’s decision to sever relations with Morocco was not exactly surprising, given that the two states have been embroiled in diplomatic disputes over support for political movements challenging the status quo.

Algiers has accused Rabat of backing the Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylie, a Berber group seeking the right to self-governance in Kabylie province, while Rabat has accused Algiers of backing the Polisario Front, which is seeking to establish Western Sahara’s independence from Morocco. Tensions on this front have been aggravated by the US government’s decision to back Rabat’s claims in Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco’s normalization of relations with Israel.

The quarrels between Algiers and Rabat have been playing out for some time and are likely to remain a source of tension for years to come, according to Hamish Kinnear, a Middle East and North Africa analyst for Verisk Maplecroft. “Relations between Rabat and Algiers are likely to remain tense for the foreseeable future,” he tells NGW. “The key sticking point of Western Sahara is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, as Morocco feels that US recognition of its claims on the territory reduce the need for compromise.”

Kinnear continues: “The severing of the GME pipeline agreement cuts off one of the few remaining areas of cooperation between Algeria and Morocco. This is despite the clear economic benefits for both sides: cheaper gas for Morocco and increased access to the European market for Algeria. Geopolitics have therefore trumped economics. Rabat is reluctant to go cap in hand to Algiers to seek renewal of the deal, while Algiers believes it can cut Morocco out of the gas equation entirely.”

Spain’s response

This ongoing quarrel has now become Spain’s problem as well.

As noted above, after Algeria cut off relations with Morocco in August, it made clear that it would not be renewing its agreement with the latter on gas transits via GME. This move obviously had consequences for Spain, which has been receiving about 6bn m3/yr of gas via the pipeline. These consequences did not play out over time, however. Instead, they unfolded very quickly, with the gas transit agreement expiring as planned on October 31, 2021, and Algerian gas shipments via GME stopping the next day.

As a result, Spain found itself facing a supply crunch for which it had little time to prepare. Moreover, it had to confront this problem at a time when its resources were limited because of the gas supply crisis that was hitting the EU at large.

As a result, Spain found itself facing a supply crunch for which it had little time to prepare. Moreover, it had to confront this problem at a time when its resources were limited because of the gas supply crisis that was hitting the EU at large.

The Spanish government did try to head off the crisis. In early October, Spanish foreign minister Jose Albares traveled to Algiers to discuss the matter. After a meeting with his Algerian counterpart Ramtane Lamamra, he told reporters that he had been “reassured about the continuity of natural gas supplies” and mentioned Algeria’s willingness to increase the volumes delivered to Spain via the Medgaz pipeline.

Then in late October, Spain’s deputy prime minister for ecological transition, Teresa Ribera, went to Algiers for another round of discussions. After a meeting with Algeria’s minister for energy and mining Mohammad Arkab, she told the press that Algiers had pledged to keep the volume of gas supplied to the Spanish market steady by increasing shipments through the Medgaz pipe and, if necessary, delivering extra LNG by tanker. She also pointed out that Spain was not in immediate danger of running out of gas, since it had enough in storage to cover about 43 days of consumption.

Algeria’s capabilities

It remains to be seen whether Algiers can actually uphold the pledge made to Ribera.

As previously mentioned, Spain has been receiving about 6 bcm per year of gas via the GME pipeline and about 8bn m3/year via Medgaz. Algeria’s national oil company (NOC) Sonatrach has said it is ready to increase Medgaz’s throughput to 10.0-10. bn m3/year (27.4-28.8mn m3/day) by January 2022, but that will only make up for 33-42% of the fuel that is usually supplied by GME.

The question, then, is whether Sonatrach can deliver enough LNG to make up for the remaining volumes that Medgaz cannot handle. This amounts to about 3.5-4.0bn m3/year (9.6-11.0mn m3/day) of gas.

Platts Analytics has suggested that the Algerian NOC will be able to meet this need. In early November, it noted that Sonatrach was currently exporting the equivalent of 44mn m3/day (16.06bn m3/year) of gas. Since it is only delivering 31mn m3/day (11.315bn m3/year), or about 70.5% of the total, under contractual commitments, it can make up to 13mn m3/day (4.745bn m3/year) available to other buyers.

In other words, Sonatrach should theoretically be able to divert enough of its own LNG to Spain to compensate for the loss of GME shipments. It remains to be seen, though, whether this remains true in practice. Algeria exports LNG via the Arzew and Skikda terminals, the latter of which spent more than half of last year offline because of technical problems. Skikda LNG also went off line for 45 days in the summer of 2021 to repair a damaged turbine, with Sonatrach saying it had decided to fix the unit rather than replace it, since a replacement might force the facility to suspend production for around 18 months.

Under these circumstances, it would be hardly be surprising if Skikda LNG were to experience another breakdown or more technical problems before the end of the current heating season. If so, Algeria will have difficulty upholding its pledge to keep gas deliveries to Spain steady, and Spain will have to mount another search for gas – and do so at a time when the rest of the EU will still be under significant supply pressure. Under those circumstances, it would probably have to buy LNG on the global market at a high price. This would, in turn, push domestic electricity prices up in Spain, thereby irritating consumers and straining the Spanish economy.

Looking for FSRUs

It might also lead Spanish gas buyers to explore other options for increasing the country’s import capacity, such as the renting of floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs). Since such vessels are in short supply, though, this plan would be costly to execute – especially in the short term, given that global gas demand is set to remain strong through the end of the Northern Hemisphere’s heating season.

If Spanish buyers pursue this option over the longer term, though, they might face stiff competition closer to home, since Morocco is looking into the possibility of using FSRUs to augment its own gas supplies. Martin Sherriff, head of the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) group at Welligence Energy Analytics, draws attention to the plans that UK-listed Predator Oil & Gas is making for future imports. “Predator has submitted a bid to build a floating LNG regasification terminal with an initial capacity of 110mn ft3/day by 2025, rising to 170mn ft3/day in 2030 and 300mn ft3/day,” he tells NGW.

Kinnear also indicates that he saw FSRUs as a possible solution for Morocco. “Longer term, Morocco could construct LNG terminals or bring in floating storage [and] regasification units (FSRU) to import gas normally supplied through GME,” he says.

According to Sherriff, Predator’s initiative might serve to help Morocco make up for any gas supply shortages in the long term. Kinnear also expressed some optimism on this front, pointing to Moroccan minister of energy transition and sustainable development Leila Benali’s statements on November 8 about preparing the country’s ports to handle incoming LNG shipments. “Tangier may be a possible location for an FSRU,” he commented.

It’s worth noting, however, that these are long-term prospects that are not likely to have much short-term impact. (Notably, Benali did not give a timeline for the execution of such a project. She said only that the Moroccan government was figuring out the technical and financial details for an FSRU plan.)

In other words, there are real limits to the amount of short-term relief that may be available to the Spanish and Moroccan gas markets during the 2021/2022 heating season. As such, both countries ought to start planning now for the 2022/2023 heating season.