Sub-Saharan Africa’s LNG prospects could be derailed by western oil majors’ shifting course [Gas in Transition]

Sub-Saharan Africa entered the LNG market with the construction in 1999 of the first two trains of Nigeria’s LNG’s complex on Bonny Island in the Niger Delta. Further trains were added between 2002 and 2007 bringing total capacity up to 18.6mn metric tons/year. Plants followed in Equatorial Guinea in 2008 and Angola in 2013, while the region’s first floating LNG facility (FLNG), the Hilli Episeyo, came online offshore Cameroon in 2018.

In 2019, Sub-Saharan African countries exported 29.3mn mt of LNG, slightly above nameplate capacity, representing just over 8% of global LNG exports.

Plants under construction, if completed on schedule, should nearly double that capacity over the next three to five years, bringing much needed investment. Mozambique’s Coral South FLNG is expected on-stream in 2022 and the first phase of Mauritania’s Tortue/Ahmeyim FLNG in 2023. These should be followed by the much larger Mozambique LNG Trains 1 and 2, although the project is currently suspended, and Nigeria LNG Train 7 coming online in 2024/25.

But whether Sub-Saharan Africa’s second flush of LNG development will be followed by a third now appears to hang heavily in the balance.

Net zero pathway

When the International Energy Agency (IEA) published its Net Zero by 2050 report in May it envisaged not the gradual withering away of oil and gas consumption, but a sharp and immediate fall in the former, followed by a similar but later peak and decline in demand for the latter. Its most startling finding was that on a net zero pathway no new oil and gas developments were needed from today beyond those for which commitments have already been made.

However, rather than represent what will happen, the IEA’s net zero scenario highlights the massive challenges faced in delivering net zero carbon by 2050. The most likely scenario, in reality, is partial success. The likelihood that there will be no new oil and gas development decisions is low. This suggests that the world will have to cope with the climatic changes produced by some degree of global warming above pre-industrial levels, a future for which Sub-Saharan Africa is least well placed to cope, given its weak economic and institutional capabilities.

Nonetheless, the direction of travel, if not the speed, seems certain and some of the trends outlined by the IEA report are likely to emerge, in particular the gradual concentration of oil and gas production in the lowest-cost producing countries. For oil, this means the Middle East and Russia, and for gas, countries like Russia, Qatar and the US.

This would appear to leave little room for the smaller African gas producing countries.

It also highlights the importance of LNG in monetising African gas assets, given the heightened uncertainty of demand created by net zero carbon policies in gas-importing countries.

Grandiose projects such as the Trans-Saharan gas pipeline, which aimed to bring Nigerian gas to European markets by pipeline via Algeria, while always borderline in commercial terms, depended fundamentally on strong and growing gas demand in Europe coupled with the exhaustion of that continent’s indigenous production.

Such projects are now dead in the water. To reach consumer markets, most likely in Asia rather than Europe, African gas producers must invest in LNG.

Yet, as consultants Wood Mackenzie wrote in their review of 2020, the year was “brutal” for Sub-Sahara Africa. Upstream oil and gas investment fell 40% and pre-financial investment decision (FID) projects were deferred and downgraded. Exploration drilling was the lowest since the 1950s with just one commercial discovery.

Oil major dependency

Sub-Saharan African LNG is heavily dependent on investment from foreign oil companies, particularly the oil majors. African national oil companies lack the capital and expertise to compensate for downturns in investment levels.

The prime movers behind Nigeria LNG were Shell, Total and Eni, while Marathon Oil developed Equatorial Guinea’s LNG plant and a consortium of Chevron, BP, Eni and Total were responsible for Angola LNG.

Along with partners from mainly Asian LNG consuming nations, Sub-Saharan Africa’s second phase of development is again being led by the majors: Eni, ExxonMobil and Total in Mozambique, BP in Mauritania/Senegal and Shell and Total in Nigeria.

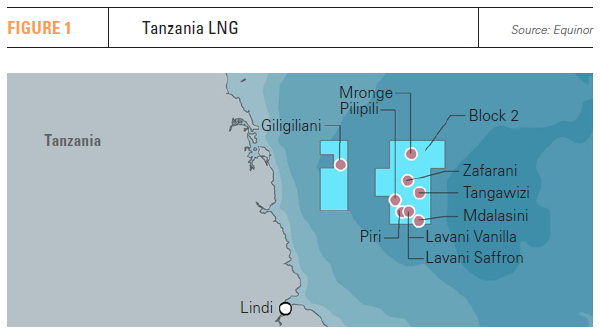

Further investments – such as the expansion of Tortue/Ahmeyim, an FID on the Rovuma Mozambique project or LNG developments in Tanzania – hang on the decisions made in western oil majors’ boardrooms.

Changing course

These boardrooms are facing new pressures and changes in their investment strategies are already evident as they increase their spend on clean energy technologies.

According to the IEA’s World Energy Investment 2021 report, published in June, “as the majors downsize their portfolios and mid-size independents struggle to access capital, smaller resource-holding countries – especially those in developing economies – are left with a smaller potential pool of investors and operators.”

According to the IEA’s World Energy Investment 2021 report, published in June, “as the majors downsize their portfolios and mid-size independents struggle to access capital, smaller resource-holding countries – especially those in developing economies – are left with a smaller potential pool of investors and operators.”

The pressure to take a more pro-active approach to climate change and come into line with 2050 decarbonisation goals is growing fast as evidenced by the decision by a Dutch court in May to order Shell to cut its greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) 45% by 2030, the first court decision to compel a company to take such measures. Although Shell has outlined a net zero strategy and has said it will appeal, the decision may push the company to act faster than it plans.

Whatever the outcome, the legal ruling is unquestionably a landmark decision in terms of environmental litigation, and one almost certain to impact strategic planning across the oil and gas sector.

At the same time, US oil major ExxonMobil has experienced a shareholder revolt, which has placed at least two new independent and environmentally-minded directors on the board. The vote reflected shareholder frustration not just with the company’s focus on oil and gas production, and its limited engagement with the energy transition, but the poor returns to shareholders which this strategy has delivered.

Oil major Chevron also faced a revolt with shareholders winning a vote calling for the company to cut its GHG emissions, including those of its customers.

The European majors were already shifting course. Shell, BP and Total have all taken a step into the offshore wind market, indicating a readiness to deploy capital which would once have been used for oil and gas exploration and development.

The sea change in investor sentiment suggests that international oil companies’ value will in future be less driven by their reserve base and replacement ratios and more by their ability to create new non-oil and gas revenue streams. This will reduce their appetite for developing marginal fields designed to shore up existing production from established producers and their interest in frontier exploration, both of which will again impact Sub-Saharan Africa.

The often difficult operating environments of Sub-Saharan countries, whether as a result of armed conflict, corruption, weak legal protections or other factors, suggest they will struggle to attract new capital investment at the same time that the oil and gas majors are re-evaluating their propensity to supply it for all but the most attractive, low-cost reserves.

State-driven strategies

In contrast, no such ambiguity exists in Russia or Qatar. Both have substantial LNG expansion plans and can forge ahead backed by privately-held companies with significant state support, like Novatek, and state-owned LNG mammoth Qatargas.

Not only are the gas resources larger in Russia and Qatar than in Sub-Saharan Africa, but so too is the financial and technical ability of indigenous companies to exploit it, while increasing LNG production remains central to state economic strategies.

Russia, led by Novatek, hopes to raise its LNG capacity from about 31mn mt/yr in 2020 to almost 140mn mt/yr by 2035. The expansion will be led by developments in the Arctic and the country’s Far East. Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 6.6mn mt/yr Train 1 is expected on stream in 2024 to be followed by two further trains of the same size in 2025 for total capacity of 19.8mn mt/yr.

Qatar’s plans are no less ambitious. It has already embarked on development of the $28.75bn North Field East project, which will raise national LNG production capacity from around 80mn mt/yr to 110mn mt/yr in 2025/26. A further 16mn mt/yr could result, if Qatar pursues development of North Field South.

In Russia, the government is supporting the development of a full LNG supply chain to cement its ability to expand its domestic LNG equipment and technology sector, in part a strategic decision to reduce the impact of US sanctions, while, in Qatar, the authorities also believe they have the experience to handle the North Field expansion alone, although they have not ruled out foreign partners.

In its net zero carbon pathway, the IEA predicted that OPEC’s share of the oil market could rise to an unprecedented 52%, although the agency hypothesised that this would not increase the organisation’s market power.

A similar trend in the concentration of LNG capacity, with hard-to-predict market impacts, appears likely as Sub-Saharan Africa loses out on oil and gas investment, and, owing to weak economies, limited innovation and governmental capabilities, struggles to find a productive role in the energy transition.

|

Independent aims to develop Nigeria’s first FLNG plant Nigeria’s UTM Offshore hopes to develop the country’s first FLNG facility. The company plans to liquefy gas produced from the Yoho field, which lies in the shallow water OML104 block, operated by ExxonMobil. The 1.2mn mt/yr plant could be up and running in 2025, depending on study results. Nigeria's department of petroleum resources issued a licence for the plant in February. UTM has two years to make a final investment decision. In May, US-based engineering firm KBR announced that it had received a contract from UTM to review the pre-front end engineering design work now underway at Japanese engineering company JGC. UTM is a privately-held company incorporated in 2012 to trade crude oil and provide a range of offshore services. |