[GGP] The Azeri Exception

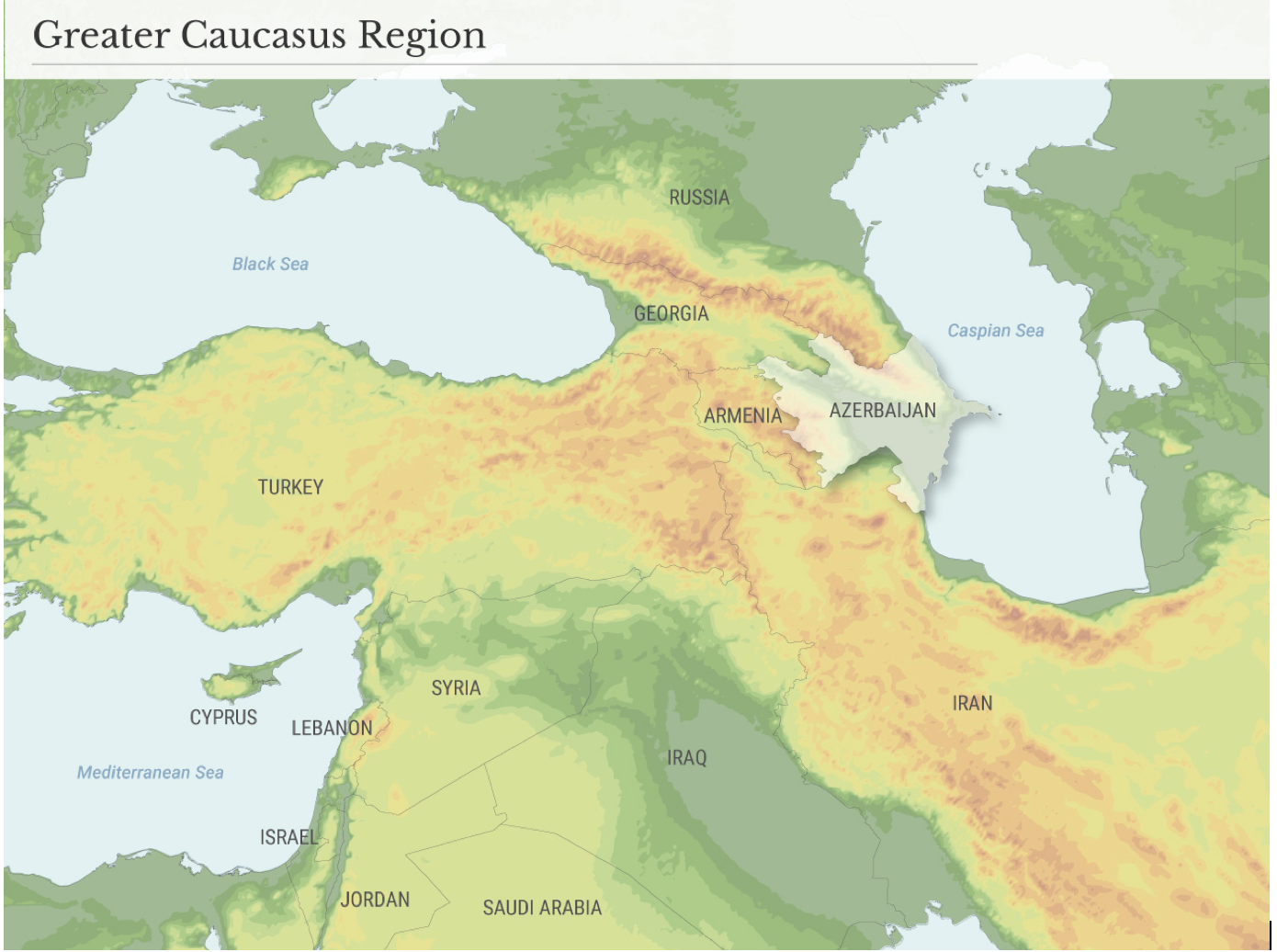

The last week of August was busy for international affairs in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. The White House national-security adviser John Bolton visited Ukraine on Aug. 24. The German Chancellor visited Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan the same week, between Aug. 23-26. The media focused on the diplomatic ties between the West and the countries in the region. Bolton and Merkel were quoted to have made various promises to the leaders of these countries to help them fight the Russian threat. But there is one thing that ties the visits together: energy geopolitics. Azerbaijan has risen in importance for both the U.S. and Germany.

In Kiev, Bolton talked about the Ukrainian gas dependence on Russia. He pointed out, again, that Nord Stream 2 is not only a business project, but its construction influences the European – and, in extenso, to Western strategy towards the Eastern neighborhood. Bolton said that Ukraine could seek alternatives to Russian imports by working with international companies to drill in Ukraine itself. He also added: “there is also gas in Azerbaijan”. He clearly didn’t mean Azeri gas could be pumped into Ukraine soon. Instead, he was pointing to alternative energy sources for Europe.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Bolton had also brought up to the Europeans – more to Germany than to Ukraine, a recent decision that the U.S. made on Aug. 6: the exemption of Iranian companies contributing to the European Southern Corridor from sanctions imposed against Iran (In the text of executive order, the waiver refers to the “Natural Gas Project Exception” (Sec. 10)). The Southern Corridor is one of the EU backed strategic corridors meant to secure access to new sources of gas from the Caspian Sea, diluting the dependence on Russian energy supply. The National Iranian Oil Company holds a 10% share in the second phase of the development of the Azeri Shah Deniz natural gas field – that would potentially feed into the Southern Gas transport corridor, to deliver Caspian gas to European clients.

The U.S. support is not unexpected. It’s not new that Washington has been supporting the development of Azerbaijan into an alternative energy source for Europe. More, the existence of a functioning alignment between countries in the Black Sea and the Caspian would come to the American interest in the region. It would contain potential risks following Russian resurgence and also help securing an important trade route, from Asia into Europe. In the same time, considering that the U.S. seeks a way out from the Middle East for some time now, it also understands Iran can only play a more important role on the longer term. Russia and Turkey will need to come to terms with that.

Recently, we have already seen some indicators pointing to the raising importance of not only Iran, but also of Central Asia for the global energy geopolitics. On Aug. 12, the countries bordering the Caspian Sea reached an agreement on the body of water’s legal status. The status of the Caspian Sea has been debated ever since 1992, when the U.S.S.R disintegrated. A functional, relevant agreement would cover not only maritime borders to fishing rights but, more importantly, the use of the Caspian Sea’s energy resources. That was not settled yet. But the fact that the leaders of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan have come together with the goal of reaching an agreement is evidence that it may be time for them to make better use of their resources, considering the business and geopolitical opportunities for them all. Such goal may be ambitious, but it is founded on a stringent short-term need. These countries’ governments need to overcome pressing socio-economic challenges at home.

These countries have kept strong ties with Russia, something that hasn’t always played to their favor, considering the economic problems Russia has been facing during the last decade. In the same time, working with Iran at a strategic level has turned out to be increasingly necessary. Some of them – Azerbaijan and (more recently) Kazakhstan have invested in bettering their relations with the West, and in particular their ties to the EU. Azerbaijan’s national interest, due to its geographic position, is to maintain the balance between the world’s major powers as a measure for keeping its sovereignty. Azerbaijan is literally the place where Europe, Russia, Turkey, Iran and where all their interests meet the American interest.

Germany has an interest in keeping the European Union united – it needs the single market to continue for the German export-based economy. While Brussels sets the legal rules of the game, it is Germany who is the de facto leader of Europe. With Poland, Romania and some other EU member states talking against the Nord Stream 2 project (Berlin’s favorite), Germany needs to show support for alternative routes that will at least attempt to keep European energy dependence on Russia in check. In Azerbaijan, Merkel stated that it supports the Southern Corridor development. Before her trip to the region, an unnamed high official of her cabinet was quoted in Financial Times saying that the agreement between the Caspian Sea littoral states could be “first step” towards the realization of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline which would bring gas from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan, “helping diversify” Europe’s energy imports.

However, in shaping up the German policy towards the Caucasus and Central Asian countries, Merkel faces, again, the inherent contradiction in German strategy. Just like in dealing with Ukraine, Germany must take a complex stance. It needs to engage in realpolitik based relations on security and energy. In the same time, Germany needs to support the fight against illiberal regimes – because Germany's status as a liberal democracy is central to its post-war self-conception. The problem is that none of the states in the Caucasus or Central Asia that Germany seeks to work with on energy security are liberal democracies. More, Germany has supported pretty much all attempts to fight these regimes that Berlin, and the West in general, see to be dictatorial.

The German interest in the region is not new, either – what is new is that Germany has officially and publicly become more pragmatic over such matters. While this is read by most as a natural German reaction to the U.S. increasingly disengaging from European affairs, reality contradicts that perception. It is because the U.S. is currently engaged in the European neighborhood and because nationalism is growing in Europe, posing an increased political risk to the EU’s future, that Germany needs to take, again, a complex but pragmatic view over the issues emerging in the Eastern European neighborhood.

The American and the German pragmatisms first meet over Azerbaijan. The need to make an ally of Azerbaijan makes it an exception to the region – Turkey, Russia and even Iran share a similar need. In the meantime, Baku will continue its careful balance. Which makes Azerbaijan the exception to the rule in the region.

Antonia Colibasanu

This article was originally part of EnVal, an energy geopolitics newsletter. Published every two weeks, EnVal is available for free. Sign up HERE

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.