The future of gas in Europe [NGW Magazine]

The claim made at the European Gas Conference (EGC) in Vienna was that gas will become the most important energy source in the EU before 2030. This is probably true: but for how long?

The EU climate change targets to 2030 -- and especially the target to remove carbon from energy by 2050 -- pose serious hurdles.

There was particular emphasis on the need for unambiguous and minimal regulatory frameworks. This is essential for developing the infrastructure needed for the energy transition.

Future of natural gas in Europe

In a keynote speech, Manfred Leitner, member of the executive board of Austrian OMV, said that political agendas often drive the European gas business, complicating what should be commercially-driven markets.

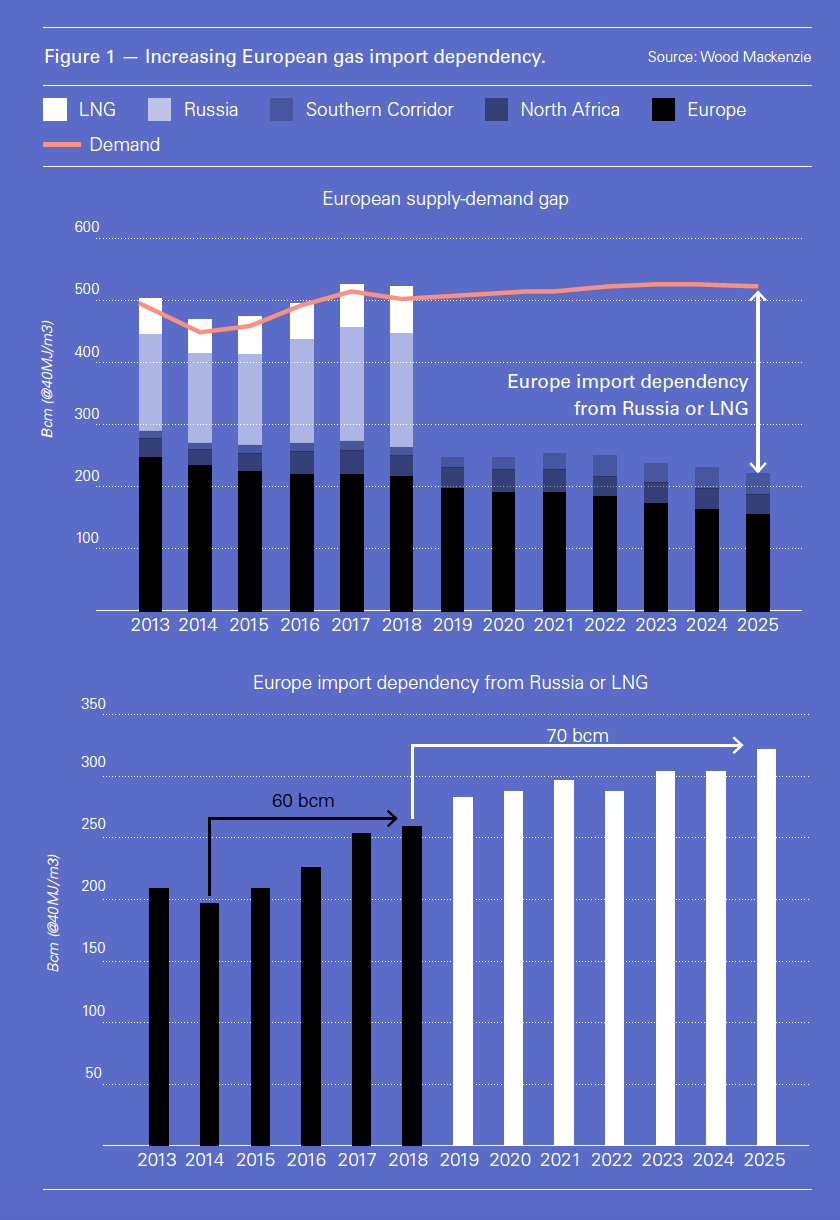

European gas production is declining faster than anticipated and Norwegian production is peaking and will start declining. This is happening at a time when climate change policies are driving coal demand down and gas demand, to replace coal, up. By 2035 Europe will need over 300bn m³/yr gas imports.

Owing to its high cost, LNG alone cannot meet the increase in demand. Experience in recent years shows that, with the tendency to be diverted to where prices are highest, LNG is less predictable in Europe with wide fluctuations depending on circumstances elsewhere in the world.

Leitner stressed that over the years Gazprom has proved to be a liable and dependable partner. Nord Stream 2 (NS2) is a market-driven project bringing gas to Europe and it is now essential to cover this growing demand. Leitner does not think that there is a credible alternative the NS 2 to meet Europe’s future gas demand reliably.

Romania can also help with recently discovered Black Sea gas. But it needs a stable and reliable regulatory and fiscal regime to achieve that and so far it does not have one. Privately-owned Black Sea Oil & Gas made that clear enough when announcing its provisional final investment decision on the Midias block.

Romania is not alone in following its narrow, national interests. He identified Ukraine and to some extent Poland as countries with their own agenda, but Europe needs a stable relationship with Russia, as the government’s energy spokesman Michael Losch agreed. The head of the internal energy market unit in the EC’s directorate-general of energy, Florian Ermacora, also said that even though there is closer co-operation between EU transmission system operators, southeast Europe does not have a good record in implementing European rules over national interests.

Gazprom board member Victor Zubkov and Elena Burmistrova, director-general Gazprom Export, presented the Russian view, noting that 2019 is the 50th anniversary of Gazprom’s deliveries to Austria.

Burmistrova confirmed that exporting over 200bn m³ to Europe and Turkey was a breakthrough and represents a new reality for Russian gas exports. Austria, Italy, Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Denmark, Bulgaria, Greece and a number of other countries had all taken more in the first 15 days of this year than they did in the same period of 2018, she said. “The breadth of this geography again stresses the demand for modern and effective gas transport systems which Gazprom is now building with its partners,” she said, referring to NS 2 and TS 2.

She went on to say that over the next few years she does not expect supply to be any lower. She also added that Gazprom piped gas will always be cheaper than US LNG.

And with Europe gradually removing coal from its power mix, gas provides an ideal solution to replace it. But with Groningen gas production being phased out, by 2040 the EU’s indigenous gas production will decline from 132bn m³/yr today to 45bn m³/yr, increasing gas import needs.

Even with increasing LNG cargoes arriving in Europe, the IEA forecasts that Russia will keep its position as the single biggest supplier to Europe, where gas will remain as the only fossil fuel in more demand than it is today.

Burmistrova said: “Many assume LNG deliveries will play a role in meeting demand... In the medium term perspective one can see additional cargoes reaching Europe, but first of all it is Asian markets that will keep their attractiveness, given their size and rate of growth.”

Nord Stream saw record gas flows in 2018 – 58.8bn m³. That was appreciably more than the nameplate capacity of 55bn m³/yr and also 15% up on the year before and the most since the line started up.

Gazprom expects to complete NS 2, TS 2 and Power of Siberia in 2019.

Uniper acting CEO Keith Martin said NS 2 is a commercial project providing Europe with gas at a competitive price and adding to security of supplies. Piped gas prices will determine how much LNG arrives in Europe. But Uniper is hedging its bets, and is developing an LNG import facility based on positioning an floating storage and regasification unit at Wilhelmshaven, the only German deep-water port.

The FSRU capacity will be 10bn m³/yr and it is expected to become operational by 2022. In support of this, Uniper has already entered into a provisional agreement with ExxonMobil for a significant part of the capacity. The US major will be exporting LNG from the US Golden Pass facility following final investment decision last month; and probably from Mozambique as well from Rovuma LNG. It already delivers LNG to Europe from Qatar.

A senior gas analyst International Energy Agency (IEA), Jean-Baptiste Dubreuil, said that the IEA is positive about the future of gas in any form. EU’s gas import demand will increase but it is still very sensitive. Challenges include gas price competitiveness and market reforms, as well as curbing methane leaks. It also needs to prove its contribution to a cleaner, more sustainable energy environment. BP European Gas & Power COO Jason Tate added that in Europe energy efficiency gains will be another factor determining longer-term gas demand.

The last time Europe experienced conditions similar to now – increased gas/LNG supplies and mild weather – was 2010-2011. It led to increased liquidity, a very competitive environment and low prices.

The European Commission and gas

The EU emission targets for 2030, and especially the target to achieve an 80% reduction by 2050, will impact the future of gas in Europe. Key issues are decarbonisation and the reduction of methane emissions – 3% leakage has been calculated to be enough to wipe out all benefits of coal-to-gas switching.

EU’s 2030 emission reduction targets and ETS encourage coal-to-gas switching, but also renewables. In this respect, the EC considers the reform of ETS last year to have been successful and sees CO2 targets becoming achievable through ETS.

In the longer-term use of gas will need carbon capture and use (CCU) and carbon capture and storage (CCS). The EC is funding some projects in their early stages through the Connecting Europe Facility, such as UK Pale Blue Dot’s Acorn project was one beneficiary. The EU wants to find places to inject industrial carbon emissions and CO2 may be compressed or liquefied and shipped to a beach terminal such as St Fergus, in Scotland, for injection offshore.

Another longer-term option is green gas produced by using surplus renewable electricity. But is it commercial at large scale? The business case has not been made yet.

Two key priorities for the EC are:

- LNG regulations

- Transmission system tariffs

New regulations are to be in place by 2022, but there will be a new commission in place by year end, following elections in April.

Other regulatory issues being considered by the EC include: tariffs for power-to-gas installations; new infrastructure for green gas, as well as its quality; hydrogen; the role of existing distribution systems; and methane leakage.

The EC is examining these by performing and supporting studies and research to assist in developing forward-looking strategies, including power-to-gas, but the EC has lately taken a back seat, announcing it is not its role to decide on what are going to be the technologies of the future, other than helping ensure a level playing field. It is for the market to decide which technologies are implemented and go forward.

Pipelines need clear rules

The senior vice-president of OMV’s international gas transport division Reinhard Mitschek summed up the European energy scene, highlighting that CO2 prices are up, LNG prices are down, European gas production is down and gas imports are up. He said that Europe needs a reliable, dependable and non-discriminatory gas transportation system. European industry needs freedom where to buy its gas and how to transport it. Policy should only specify the regulatory framework and avoid over-regulation.

Given the increasing gap between demand and domestic gas supplies, and the high cost of LNG, Europe may need more gas pipelines – not just Nord Stream 1 and 2 and TurkStream 1 and 2.

The CFO of NS 2, Paul Corcoran, told the conference that European indigenous gas production is declining fast, with the gap between demand and supply widening faster than anticipated.

Last year, when the ‘beast from the east’ brought temperatures in Europe down to very low levels, Gazprom pipeline gas stepped up at short notice, with a ten-day record set. This helped Europe ensure that the gas needed to respond to the abnormally cold weather became readily available.

The EU gas market works well. Legislators should allow the market to decide on implementation of policies and regulations.

The controversial subject of gas transit through Ukraine was addressed by Danila Bochkarev, senior fellow East-West Institute. The forthcoming presidential elections in March and parliamentary elections later in 2019 in Ukraine, as well as European elections in May, are likely to delay the Gazprom-Naftogaz negotiations. Much depends on the results of these elections, and particularly of the presidential elections in Ukraine. In any case, the mandate to negotiate an agreement is slipping away as the elections are approaching.

The preferred outcome is for the two countries to reach agreement and keep the transit route open, but given election timing this may not be possible until next year.

Faster than expected decline of gas production in Europe may require this route to remain open in the longer-term. But its longer-term reliability requires the rehabilitation of the transit system.

Role of gas in energy transition

The case for the role of gas in a low carbon future was made by Peder Bjorland, vice-president natural gas Equinor. He said that CO2 reduction is key, impacting the role gas will play in future. Gas is a cost-efficient enabler to a future carbon-neutral energy system. It is best for integrating with renewables, and it is flexible and affordable.

Bjorland described a 3-stage process to deliver a carbon-free system:

- By 2020: Gas displacing more carbon-intense fuels in transport, heating and power, reducing CO2 emissions by 20%

- Between 2020 and 2030: A combination of gas and renewables reducing gas emissions by 40% - in line with EU targets

- Between 2030 and 2050: Hydrogen and renewable electricity smartly integrated, reducing CO2 emissions by 90%.

This can be done by decarbonising gas as hydrogen, which can then be used in power generation, in heating and in transport. An example is the H21 project launched by Equinor in the north of England to decarbonize residential heating.

Conversion of gas to hydrogen, combined with CCS, will be needed to achieve 2050 targets. Supportive climate and energy policies by the EU will be essential to bring about this change.

OMV’s vice president for innovation and advocacy Michael Woltran also sees gas as part of the solution during energy transition.

Gas can keep coal out - with a 40% to 50% reduction in emissions in comparison to coal - and with a huge impact on climate change. It can also contribute to greening mobility, through the use of CNG or LNG in heavy-duty vehicles (HDV) and LNG in shipping.

An HDV requires a metric ton of diesel or LNG where an electric HDV needs 15 mt of lithium batteries. Even if the technology evolves it will still need 6 mt solid-state batteries. Substituting diesel with LNG brings emissions down by 20%. This also applies to shipping.

Burmistrova agreed that the gas industry can offer an intelligent and elegant solution for a low carbon future that allows a significant use of existing gas pipelines. This is hydrogen. Gazprom thinks that using a mix of methane and hydrogen in electricity and transport could cut emissions by 25 to 35% and thereby achieve the EC climate target for 2030.

Defining the new business model

So what is the gas business model in a low carbon world? Gas can be decarbonised using surplus renewable electricity through various processes, such as steam methane reforming (SMR) or pyrolysis. Through such methods gas can become the stream – not just the bridge – in a decarbonised world.

RWE Supply & Trading’s CCO Andree Stracke said that the agreement to phase out coal in Germany by 2038 was ground-breaking (no pun intended). In fact coal demand may be reduced by as much as two-thirds by 2022 with early retirement of about 18GW coal-fired power generation. Germany is also in the process of phasing-out nuclear, planning to shut-down 6GW nuclear generation. This provides opportunities for gas.

But without decarbonisation, the danger is that coat-to-gas switching may be limited, overtaken by renewables.

Looking into the longer-term Stracke sounded a warning note. Over-regulation does not help the industry. Rigid rules kill development.

The policy officer for climate action and decarbonisation Pierre Dechamps, in the EC directorate-general for research and innovation, talked about the EU low carbon strategy to 2050. The role of gas during transition depends on its ability to replace coal and nuclear. But if not greened, gas may be pushed out of Europe’s future energy mix within 10 to 20 years.

There is a need for R&D to make decarbonisation of gas practical and affordable and to raise awareness and address the social impact of change. CCS is a key priority within EU R&D framework programmes. Natural gas infrastructure will also need to evolve to allow its future use to transport and store hydrogen. These developments are essential to maintain a role for gas both during the transition and in the longer-term. The objective is clear – deep decarbonisation consistent with EU’s 2050 strategy.

CAM muddies the waters

A senior research fellow Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), Katja Yafimava said the complexity and lack of clarity on the future of the EU’s regulatory framework suggests very few gas pipelines -- except for those already under way (Figure 1) -- will get built. This tilts the playing-field in favour of LNG for which no such considerations exist.

Eight years after the third energy package (TEP) was adopted, the capacity allocation mechanisms (CAM) were established only in March 2017. But these did not fully resolve the regulatory treatment of additional capacity.

Many new pipelines, which were initiated under TEP, were developed based on TEP exemptions, open season procedures, and inter-governmental agreements. This meant that new pipeline capacity was allocated and contracted under different regulatory regimes from the regulatory framework established by CAM.

These problems have been made more difficult by the ongoing politicisation of EU gas regulation, particularly in respect of Russian gas and NS 2, with the EC now trying to launch new legislation. This is creating uncertainty and will undermine the construction of new pipelines, without adding to security of supplies, she said. The recommendation was that projects initiated prior to the CAM network codes entry into force should proceed under the rules which were in place at the time of their initiation.