The greatest threat to human health [NGW Magazine]

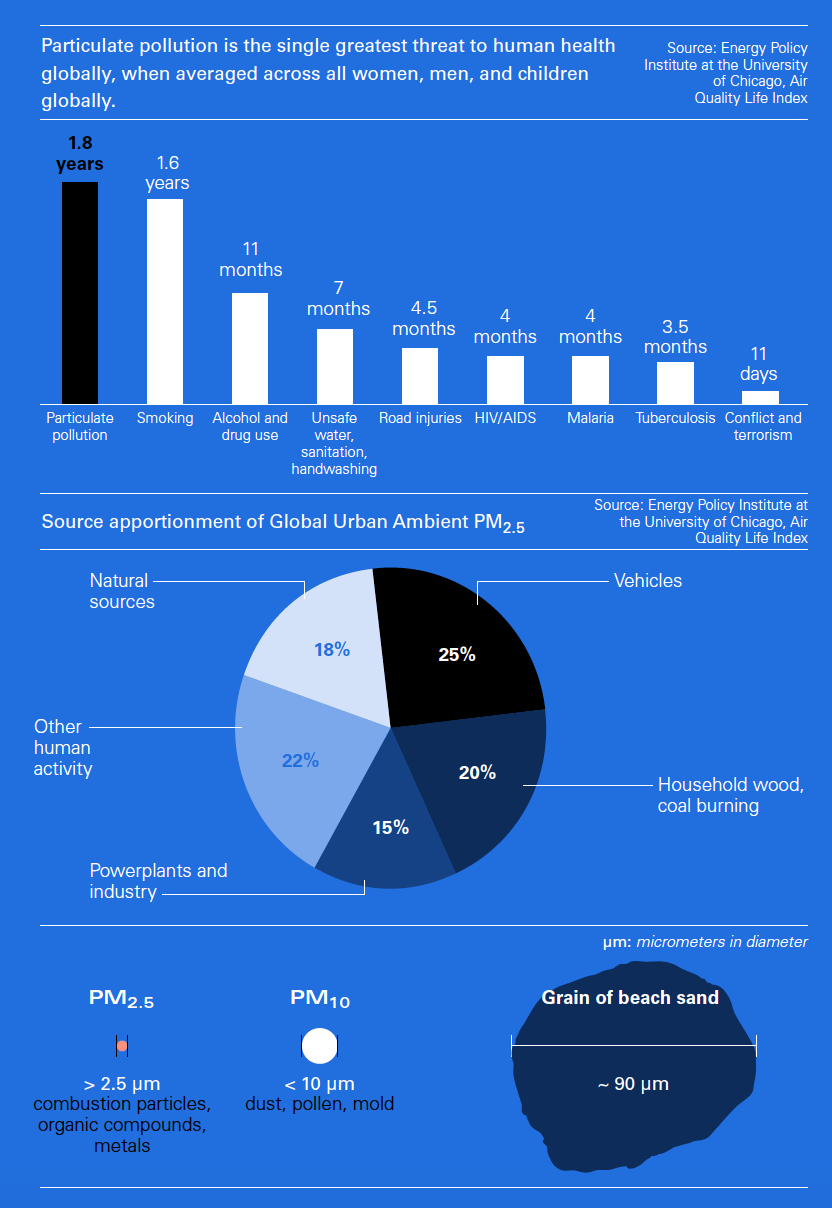

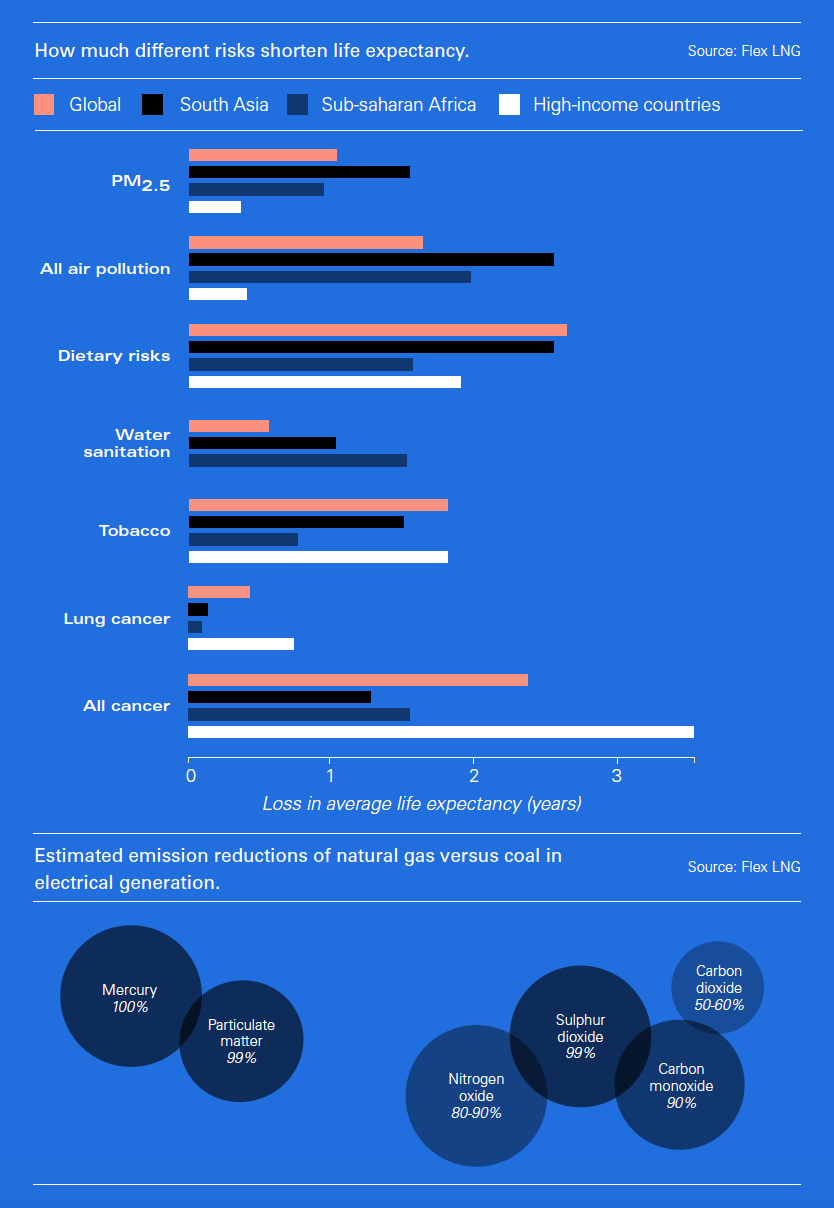

Air pollution reduces global life expectancy by nearly two years globally. So while carbon dioxide emissions have captured the headlines where medium-term doom is concerned, it is particulates that we need to worry about today, according to a new pollution index and accompanying report.

Published by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (Epic) November 19, its Air Quality Life Index (AQLI) establishes particulate pollution as the single greatest threat to human health globally, with its effect on life expectancy exceeding that of devastating diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, behavioural killers such as cigarette smoking, and even war.

Three out of four people on this planet – 5.5bn – live in areas where particulate pollution exceeds the UN World Health Organisation’s guideline of 10 micrograms (μg)/m³ of air

“Around the world today, people are breathing air that represents a serious risk to their health,” says Michael Greenstone, who co-wrote the report with Qing (Claire) Fan, a fellow at Epic.

They calculate that the average loss in life expectancy caused by particulate pollution worldwide has increased from one year in 1998 to almost two years in 2016.

This is not spread evenly around the world. For example, in the US where there is less pollution, life expectancy is cut short by just 0.1 years relative to the WHO guideline. Nonetheless a third of the US population lives in areas that do not meet the WHO guideline.

In China and India, where there are much greater levels of pollution and which together account for 36% of the world’s population, bringing particulate concentrations down to the WHO guideline would increase average life expectancy by 2.9 and 4.3 years respectively. Those two nations alone account for 73% of all the years of life lost to particulate pollution, the AQLI reveals.

In India, those extra 4.3 years would extend the average Indian’s life expectancy at birth from 69 to 73 years; but again this is not evenly spread: in the worst-affected cities the picture is much worse. AQLI shows that air quality in India’s capital Delhi is among the country’s most deadly, with particulate concentrations there in 2016 averaging 113 micrograms/m³ – thus reducing life expectancy by 10.2 years for the typical resident, compared with the longevity he might hope for if Delhi met the WHO guideline.

But several other cities in the northern region of Uttar Pradesh are as deadly: with life expectancy reduced by 11.1 years in Bulandshahr; 9.5 years in Lucknow; and by between 8 and 9 years in seven of the region’s other cities.

The report elaborates on 12 key facts associated with air pollution. Fact 1 describes particulates as “tiny and pernicious invaders of the cardio-respiratory system” that can lead to lung disease, cancer, strokes and heart attacks by penetrating deep into the lungs’ alveoli, entering and restricting blood vessels. Smaller than 2.5 μg, such particulates are even now being investigated as possible causes of lower cognitive function, and dementia.

Switching from coal to gas helped China

Fact 2 is that “energy production is the primary source of particulate pollution” and the report adds that, while some particulates arise from natural sources such as dust and wildfires, “most 2.5 μgpollution is human-induced.” More than four-fifths of such particulates are man-made.

Diesel engines, coal-fired power plants, and the burning of coal and wood for household fuel all involve “incomplete combustion.” Shutting coal-fired plants or converting them to natural gas have helped improve air quality in China since 2013, the report stresses and life expectancy has risen too.

Such ‘black carbon’, a component of this 2.5 μg pollutionis also “the second- or third-most important contributor to climate change after carbon dioxide and perhaps methane,” the report adds. So tackling particulates not only improves human health but also combats air pollution.

China indeed is ‘winning its war on pollution’ according to Epic report’s Fact 12. Such 2.5 μg pollution between 1998 and 2013 increased by nearly 75% on average across the country, the report notes, rising to more than four times the WHO safe level, with the northeast worst affected. At 2013 levels, particulates reduced life expectancy by 3.4 years for the typical Chinese citizen.

But prime minister Li Keqiang’s ‘war on pollution’ – setting out air improvement targets by end-2017, among which were restricting cars in big cities and prohibiting new coal-fired plants in some regions and requiring some existing ones to switch to natural gas – has been positive.

Beijing residents in 2016 were exposed to 6% less particulate pollution than in 2013, equating to a 0.4 year gain in life expectancy. In Henan, the province that saw the largest pollution reduction, residents are exposed to a fifth less particulate pollution than in 2013, equating to a 1.3-year gain in average life expectancy. And Tianjin, one of China’s three most-polluted cities in 2013, saw 14% less particulate pollution in 2016. If this can be sustained, Tianjin’s 13mn residents can expect to live 1.2 years longer on average than they could at 2013 levels.

The report does not mention this, but it is clear that new gas infrastructure at Tianjin has facilitated this improvement. CNPC hired a new floating LNG terminal (FSRU) from Engie starting late 2013 for five years to enable the city’s energy mix to be cleaned up. In February 2018, Sinopec opened a new 4bn m³/yr onshore import terminal there replacing the original FSRU, and it was supplemented by a newer FSRU chartered from Hoegh LNG to CNPC which started up November 2018 and which has capacity to regasify 7.75bn m³/yr.

China’s particulate pollution overall has declined by 12% in just three years, resulting in a gain in life expectancy of 0.5 years, the AQLI report says. But based on 2016 levels, that still means the average person in China would live 2.9 years longer if particulate pollution nationwide met the WHO guideline of 10 μg/m³. And it is the same in key cities: residents of Beijing could expect to live an extra 5.7 years; those of Tianjin an extra 6.1 years; and five other large northeast cities between six and seven years longer if the air met the same WHO guideline.

Proving the link, and mapping with satellites

The report says that studies going back over 60 years or more have linked particulate pollution to health, but have often left two questions unanswered: how many years of life were lost across the population because of particulates; and what are the long-term impacts of sustained exposure? It says more recent evidence over the past five years from China establishes a causal relationship between higher mortality rates in certain areas and particulate exposure, finding from 2017 research by Avraham Ebenstein and others in 2017 that “an additional 10 μg/m³ of 2.5-μg matterreduces life expectancy by 0.98 years.”

The AQLI has also used hyper-localised satellite pollution measurements, plus simulations, that have been cross-validated and interpolated using available ground-based monitoring data, which has enabled it to generate a dataset for 100 km² – so down to one-eighth the size of New York City and a fortieth the size of Beijing – for each year from 1998 to 2016.

Among other populous countries where achieving the WHO guideline for particulates could significantly increase life expectancy are Bangladesh (4.2 years) and Pakistan (2.7 years) in both of which more gas is now being introduced by the government. Perhaps more surprising is the inclusion of Nepal (4.4 years), Congo-Brazzaville (2.3 years) and Thailand (2.1 years).

In contrast, particulate pollution in the US declined by 62% between 1970 and 2016, increasing life expectancy for the average American over that period by 1.5years – just as it has been decreasing over that period in places like China, India and Bangladesh.

The report concludes that London, Osaka and Los Angeles in their day were known as highly polluted cities, but are now rich and vibrant having cleaned up their air through the application of “forceful policies” – evidence, the report urges, that today’s pollution does not need to be tomorrow’s fate.

World Bank sees Huge Scope to Invest in Asian Cities

With 1.2bn more people expected to live in Asian cities in 35 years’ time, the region’s cities have the potential to attract more than $20 trillion in climate-related investments in six key sectors by 2030, according to a new report by International Finance Corporation, part of the World Bank.

Climate Investment Opportunities in Cities analyses cities’ climate-related targets and action plans in six regions, identifying opportunities in priority sectors such as green buildings, public transportation, electric vehicles, waste, water, and renewable energy. It highlights innovative approaches that cities are already using to attract private capital and build urban resilience, citing for instance how biogas from landfill is being developed in the city of Mandalay in Myanmar (Burma).

Asia-Pacific has the highest climate smart investment potential of any region in the world, with by far the biggest opportunity in green buildings, alone estimated at $17.8 trillion by 2030, the report adds.

With more than half of the world’s population today living in urban areas, cities consume over two-thirds of the world’s energy and account for more than 70% of global CO2 emissions. How cities address climate change will be critical to efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 °Celsius, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“There’s a great urgency to address climate change – we must take meaningful action now,” said IFC CEO Philippe Le Houerou. Pointing to an opportunity for a low-carbon transition in cities, IFC’s regional director for East Asia and the Pacific Vivek Pathak singled out Indonesian capital “Jakarta where there’s about $30bn investment opportunity, particularly in green buildings, electric vehicles and renewable energy. The report shows megacities in Asia also have significant potential for investments that yield emission reductions.”

In Asia Pacific, the report estimates the investment potential in green buildings is $17.8 trillion; in waste $104bn; public transport $352bn; renewable energy $407bn; climate-smart water $571bn and electric vehicles $783bn.