The tie that binds Russia and China [NGW Magazine]

Even for a company as large and as capable as Gazprom, the Power of Siberia pipeline has been a formidable challenge. So it was no mean achievement when – on 2 December, some three weeks ahead of the original schedule – the presidents of Russia and China, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, and the heads of Gazprom and the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC), Alexei Miller and Wang Yilin, took part in a video conferencing ceremony to laud the start of gas flow.

Gazprom describes Power of Siberia, its first pipeline connection with China, as “the most ambitious investment project in the global gas industry.” Including field development and compressor stations, it has cost it trillions of roubles – it was all sourced internally – and the steel has to withstand ambient temperatures from -60 °C to +40 °C.

Filling the gap

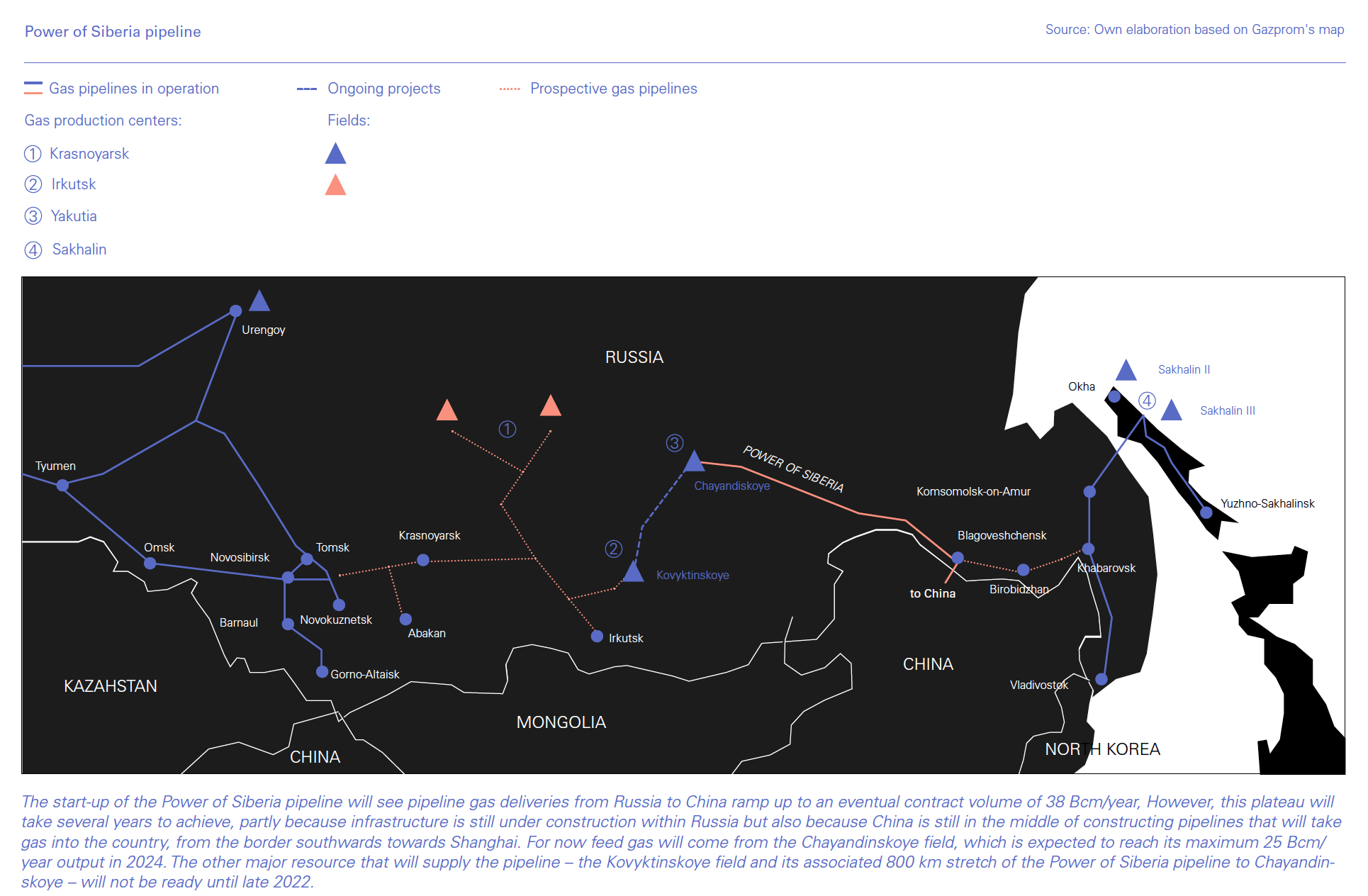

The section that has started up stretches 2,200 kilometres from the Chayandinskoye gas field in Yakutia to north-eastern China, crossing the River Amur. It is bringing gas to regions beyond the economic reach of pipelines from the coast that are desperate for more supply.

The Chayandinskoye field is due to ramp up to its design output of 25bn m³/yr by 2024. Meanwhile, another 800-km stretch of pipeline is under construction from “the most prolific field in eastern Russia” – Kovyktinskoye in Irkutsk – to Chayandinskoye (see map above).

Production at Kovyktinskoye is due to begin in late 2022, and by around the middle of the next decade, the two fields will be supplying the 38bn m³/year that China and Russia signed up to in 2014 – in a contract that at the time was reckoned to be worth some $400bn, with no calculations for this figure produced. To put that in context, China’s gas imports in 2018, when it became the world’s largest importer, were 124bn m³. So when Power of Siberia reaches plateau it will be a major and fixed contribution to Chinese supply.

Slow burn

For now, however, Power of Siberia’s impact on China’s gas supply/demand balance will be modest. Along with the constraints that exist on the Russian side, there are constraints within China, which is still in the middle of constructing pipelines that will take gas deep into the country, from the border southwards towards Shanghai. In 2020, the pipeline is expected to supply less than 5bn m³, rising to around 10bn m³ in 2021.

Moreover, most of this gas will be going to regions where there are supply shortages and so will help with an ongoing switch from coal to gas in residential, commercial and industrial sectors in areas far inland and starved of gas by infrastructure constraints.

Since 2015 China has been by far the world’s fastest growing gas market, but over the past year its previously spectacular rate of growth has slowed significantly. Between 2015 and 2018 demand grew from 195bn m³/year to 280bn m³/year, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.8%.

A report recently published by the National Energy Administration, the State Council and the Ministry of Natural Resources – the China Natural Gas Development Report 2019 (CNGDR 2019) – expects consumption in 2019 to be “around 310bn m³, an increase of around 10% year-on-year.”

This is partly because of a slow-down in economic growth to around 6%/year and partly because demand has grown so rapidly that import and delivery infrastructure has been overwhelmed – despite huge programmes to construct new LNG import terminals, pipelines and storage facilities, and government pressure on producers to ramp up domestic output.

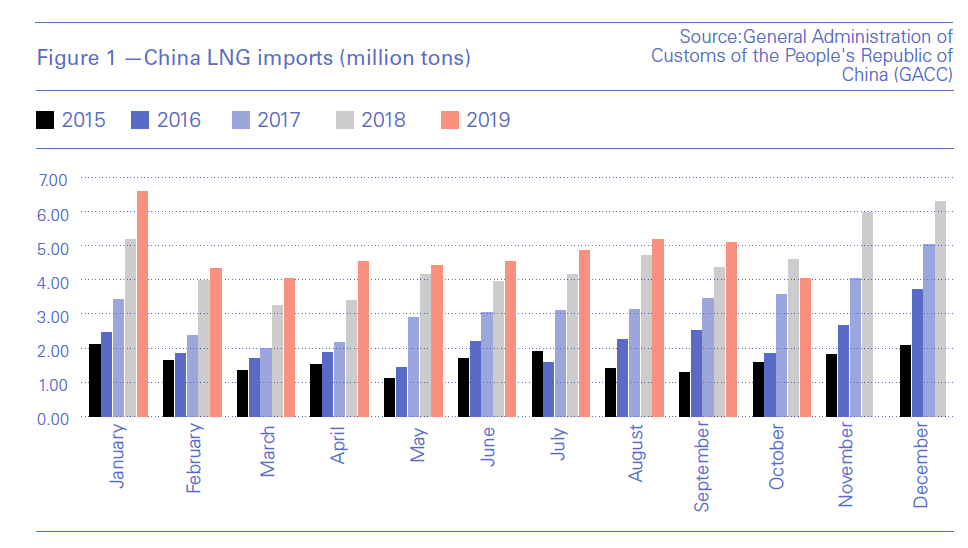

This has led to a marked slow-down in the growth of imports by pipeline and in the form of LNG.

The charts below are based on statistics published by the General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China (GACC). They show that in October of this year LNG imports were lower than they were in October 2018, the first year-on-year monthly drop since July 2016. Imports in the 12 months ending October 2019 were 18% higher than in the 12 months ending October 2018. While still a relatively robust rate of growth, it compares with a 46% rise between 2016 and 2017.

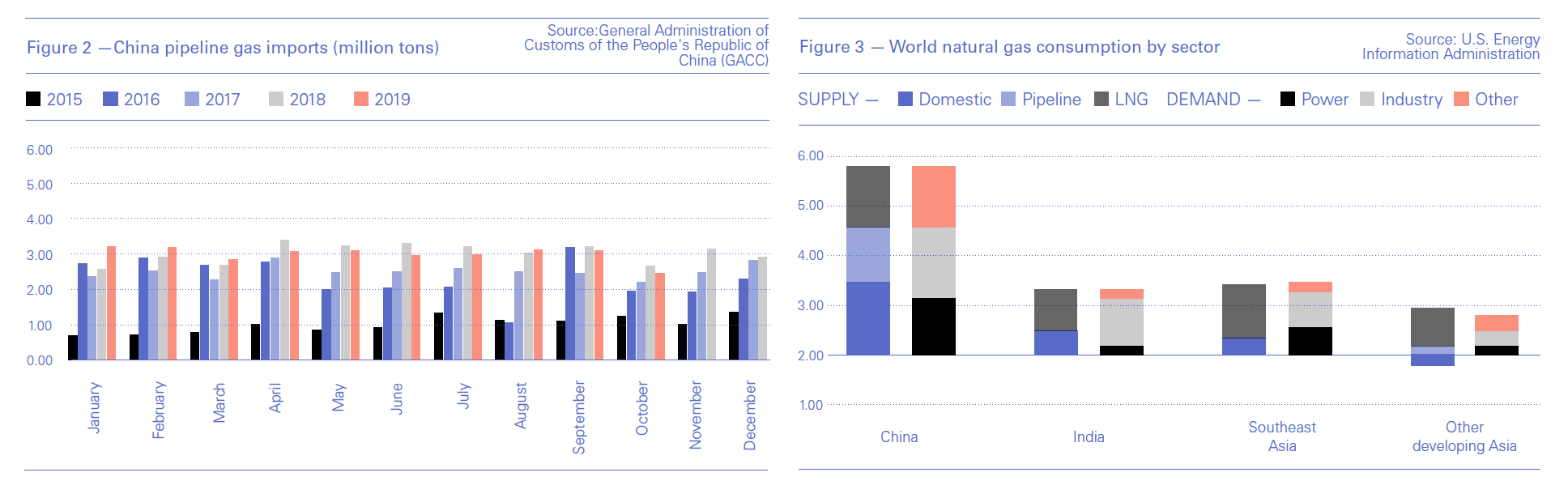

Meanwhile, pipeline gas imports – mainly from Turkmenistan – have flat-lined, with imports during the 12 months ending in October 2019 just 1.5% higher than in the 12 months ending in October 2018. This compares with growth of 124% between 2015 and 2016.

Various media reports have suggested that there has been a shift away from China’s policy to switch where possible from coal to gas – especially in the residential, commercial and industrial sectors – to ameliorate air pollution in major cities.

The CNGDR 2019 report suggests otherwise. It is peppered with language from various official documents exhorting all the relevant entities to continue doing all they can to boost gas production and to build extra import, transportation and storage infrastructure. Storage has become a big issue because of the seasonality of China’s demand. In 2018 the daily peak exceeded 1bn m³ for the first time.

The shift that has taken place – largely because of the gas supply crisis of winter 2017/18 – is a move from over-enthusiastic application of coal-to-gas switching policy by local officials, attempting to meet targets set by the Central Committee of the Communist party, to a more pragmatic approach that takes account of the actual availability of gas supply and gas appliances such as boilers.

This shift helped to ensure that there was no such crisis during the winter of 2018/2019 and there have been no reports – as of early December – of any major supply problems this winter.

Challenging targets

In 2018, the proportion of primary energy supply met by natural gas was 7.8%, up 0.8% on the previous year, suggesting that the lower end of the 8.3-10% range for 2020 specified in the 13th National Five-Year Plan for Natural Gas Development, published by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in 2016, is likely to be achieved.

The upper limit – the level specified in China’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) climate pledge under the 2015 Paris Agreement – looks more of a challenge. As for the 15% target by 2030, it is too early to say.

Growth in domestic gas production continues to lag demand growth. According to the CNGDR 2019 report, output reached 160.3bn m³ in 2018, up 8.3% on the previous year. Of this, 10.9bn m³ were shale gas, 4.9bn m³ were coal-bed methane and 4.9bn m³ were synthetic gas produced from coal. Shale gas output in particular has failed to meet expectations.

A consequence of major concern to the Chinese government is that import dependence is rising fast, with all that this implies for supply security and price exposure. Data published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its recent World Energy Outlook shows import dependence in 2018 reached 43%. It is projected to rise to 53% by 2030.

In its central Stated Policy Scenario (SPS), the IEA projects that China’s gas demand will rise to 533bn m³ by 2030 and 655bn m³ by 2040. Even in its Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), which is consistent with the climate targets in the Paris Agreement, demand rises to 508bn m³ by 2030 but then declines to 497bn m³ by 2040 as the 2050 deadline for net-zero carbon emissions looms.

The chart below shows that in the SPS, between 2018 and 2040 China's gas demand increases by more than the rest of developing Asia combined – supplied by domestic production and imports of LNG and pipeline gas. Elsewhere in developing Asia, growth is underpinned by LNG imports.

The IEA is much less bullish about growth in domestic production. In the SPS, it projects growth from 160bn m³ in 2018 to 250bn m³ by 2030 and 306bn m³ by 2040.

It therefore comes as no surprise that the CNGDR 2019 report stresses that: “Enterprises are encouraged to ‘go abroad’ and actively participate in the exploitation and development of international gas resources and the investment and operation of international LNG liquefaction projects.”

Chinese companies are already participating in LNG liquefaction projects in Canada, Mozambique and Russia, with equity interests and offtake commitments. Further involvement therefore looks highly likely and it will be interesting to see what the involvement of Chinese companies may be in the massive expansion of LNG production capacity planned by Qatar.

Acquisition of more foreign LNG interests aligns well with Xi Jinping’s all-encompassing and controversial, “Belt and Road Initiative”.

China’s growth as a gas demand centre has re-ignited interest in a second Russia-China pipeline, via the so-called “western route”.

This proposal was formerly known as the Altai pipeline but the name has fallen out of favour and Gazprom now calls it “Power of Siberia 2”. Competitions have been organised to come up with a better name. For a while this pipeline disappeared from Gazprom's maps but talks with China have restarted. Previously, the idea was to route the pipeline via the short stretch of border between Kazakhstan and Mongolia, but it now looks likely that it may go into Mongolia and then into western China. The Mongolian government has said it favours that route, no doubt thinking about the transit fees.

It will take years for such a project to come to fruition. China and Russia have yet to agree a sales and purchase agreement for supplies by this route. It would then take several years to construct the pipeline and bring it on stream. Nevertheless, the bear and the dragon have shown that such projects can be done.