This is not a drill: key lessons from GB power price spikes

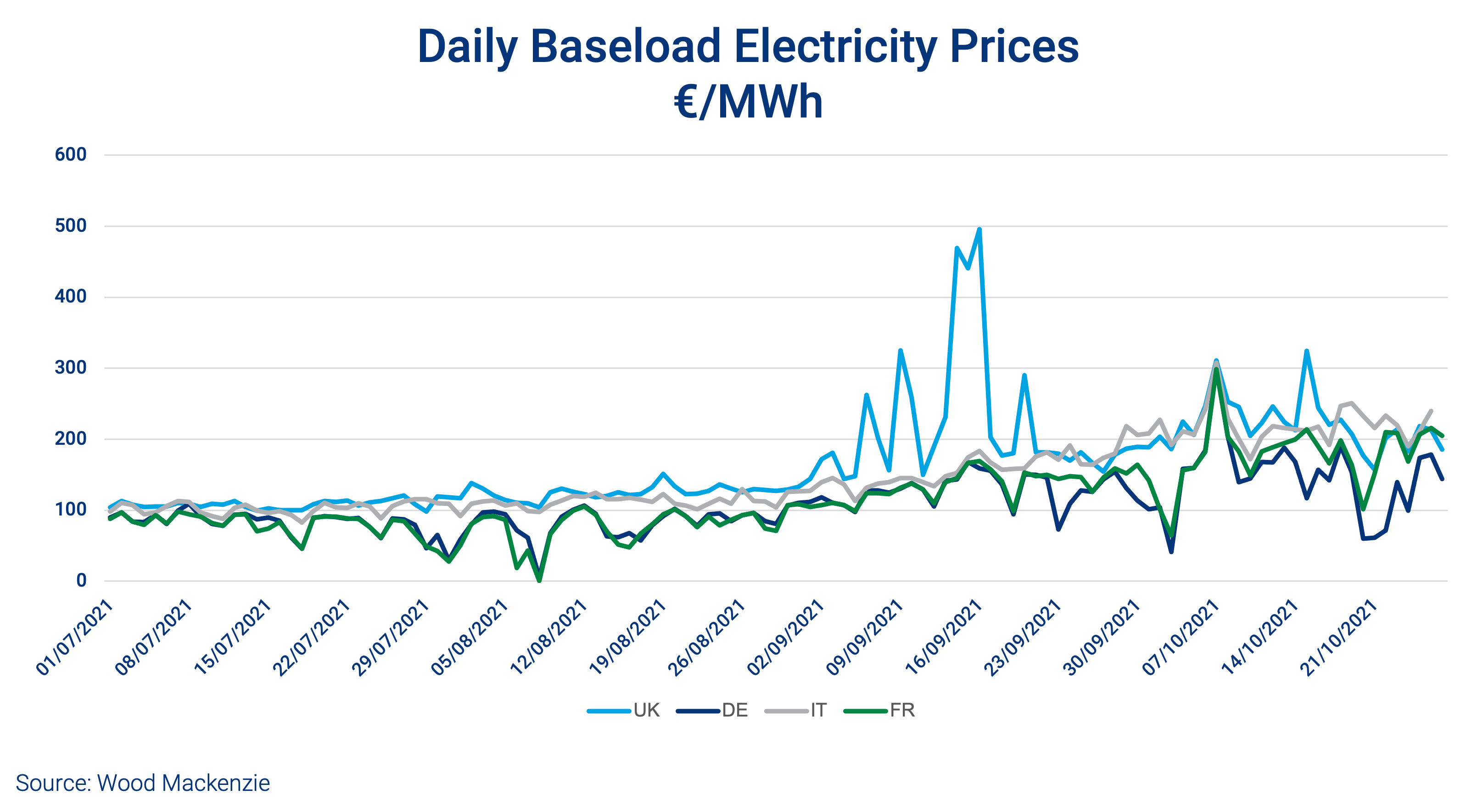

As almost everyone is aware, power prices have spiked significantly across Europe in recent months. In Britain, the market has suffered from a painful combination of high commodity prices, pre-winter levels of availability and low wind output. Now, more than a month on from the initial spikes, high prices are still a feature across the region. With limited liquified natural gas (LNG) available to European buyers and high rates of storage injection necessary through the summer, to replenish stocks used during winter 2020/21, gas prices have climbed to record highs. And as gas prices rose so did coal and carbon, trading at up to $172/t and EUR 63/tCO2 respectively in September.

With commodity prices up, GB power prices were further affected by unseasonably low wind output. In fact, during the first half of September, wind production was down 55% on the same period in 2020 and 45% lower than the 5-year average.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

These low wind speeds added to the pressures of higher commodity costs and availability issues, pushing power prices up and highlighting the increasingly important role of flexibility in power systems.

Going into winter, wind’s contribution should increase, easing the pressure on the market balance. The UK plans for wind to contribute 52% of the country’s power supply by 2030 – up from 22% in 2020 (and now the Government’s latest plans are aligned to net-zero power by 2035). Power sector decarbonisation is firmly positioned centre-stage for the energy transition, but the auction-based procurement of so much new wind capacity will do little for security of supply or the flexibility needs of the system.

In early September, the GB power market balance began to tighten, with numerous generators and interconnector capacity undergoing planned maintenance ahead of winter – a typical situation during the autumn ‘shoulder-month’ period. A subsequent lull in wind production saw system margins fall. National Grid – whose primary role is to ensure the safe operation of the power system – called on 500 MW of coal-fired capacity from EDF’s West Burton A plant and balancing prices surged to over £3,000/MWh.

Then, in mid-month, a fire broke out at IFA 1’s Sellindge converter station, one of the two GB-FR interconnectors, forcing the removal of half of the 2 GW link’s capacity for the remainder of the winter. Day-ahead power prices, which had already spiked to £540/MWh before falling back to £385/MWh, rose to £480/MWh, while within-day prices hit a weekly peak of £1,675/MWh.

An imperfect storm

In isolation, none of these events – periods of temporary system tightness, plant and equipment outages – are particularly unusual. Power markets are complex systems with many moving parts and are exposed to many influences. Energy systems, gas as well as power, have always been exposed to such ‘shoulder-month’ events, when supply and system availability are below peak levels and there is increased uncertainty around demand. These events are usually short-lived.

This time around, though, the challenge of maintaining market balance is complicated by the retirement of coal-fired generators and the push towards decarbonising European power. Coal has historically been a key provider of flexibility and being unable to call on it as before, we’ve seen a reduced amount of flexibility available to support the increasing volume of variable renewable supply.

While GB reserve margins are tighter than usual, they remain adequate, but every winter has its sensitivities. This winter, the availability of gas-fired capacity and low wind are the biggest potential threats to the security of supply.

How do European power markets overcome a yawning flexibility gap?

The challenges faced by the GB market are not exclusive to the UK. Island markets such GB and Ireland – and even partially “islanded” ones, such as Spain and Italy – risk being exposed to flexibility pressures ahead of more interconnected markets. But, across Europe, coal and nuclear phase-outs are accelerating the erosion of system flexibility, while variable supply volumes continue to grow. There’s a real and growing need for gas’ flexibility but the economics of existing operators are difficult, and unsupported new-build presents a substantial and unattractive risk.

In order to maintain security of supply, European power markets need effective mechanisms to deliver flexible plant. Various capacity market designs exist across the region, perhaps the answer lies in identifying the most effective model, to properly recognise the value of flexibility in a similar manner to the decarbonisation benefits of renewable power? It may not be the most popular development option, but gas-fired generation has a vital role to play in bridging the flexibility gap. Interconnection is another essential component of the response, complementing gas rather than replacing it, while the role of other flexible options, such as batteries, demand response and decarbonised thermal plants, develops.

The full report can be downloaded here.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.