Trade wars threaten gas market outlook [NGW Magazine]

This year’s BP Energy Outlook considers what might happen if global trade disputes escalate. It’s a prospect that threatens to heighten energy security concerns and push countries to produce more and import less – China being a case in point, with its higher coal burn.

The key points drawn by BP are:

- International trade has an important influence on the global energy system: it underpins economic growth and also allows countries to diversify their sources of energy.

- If the recent trade disputes escalate they could have a significant impact on the energy outlook.

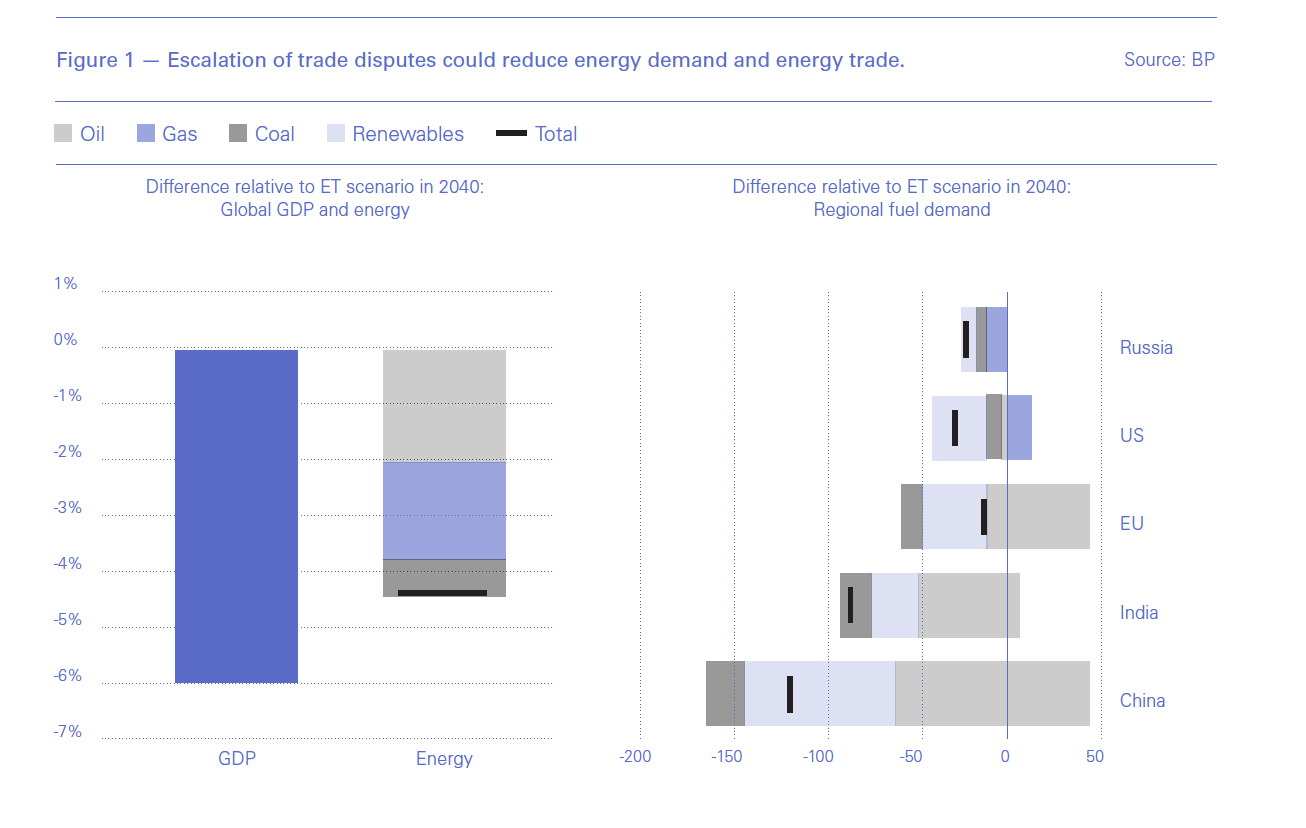

- A slower GDP growth trend would reduce the level of world GDP in 2040 relative to BP’s Energy Transition (ET) scenario by 6%, and energy demand by over 4%. Those falls would be concentrated in countries and regions most exposed to foreign trade and in fuels, oil, gas and coal (Figure 1).

- This general pattern is also evident in individual countries: lower energy demand and a shift in the fuel mix towards domestically-produced sources of energy.

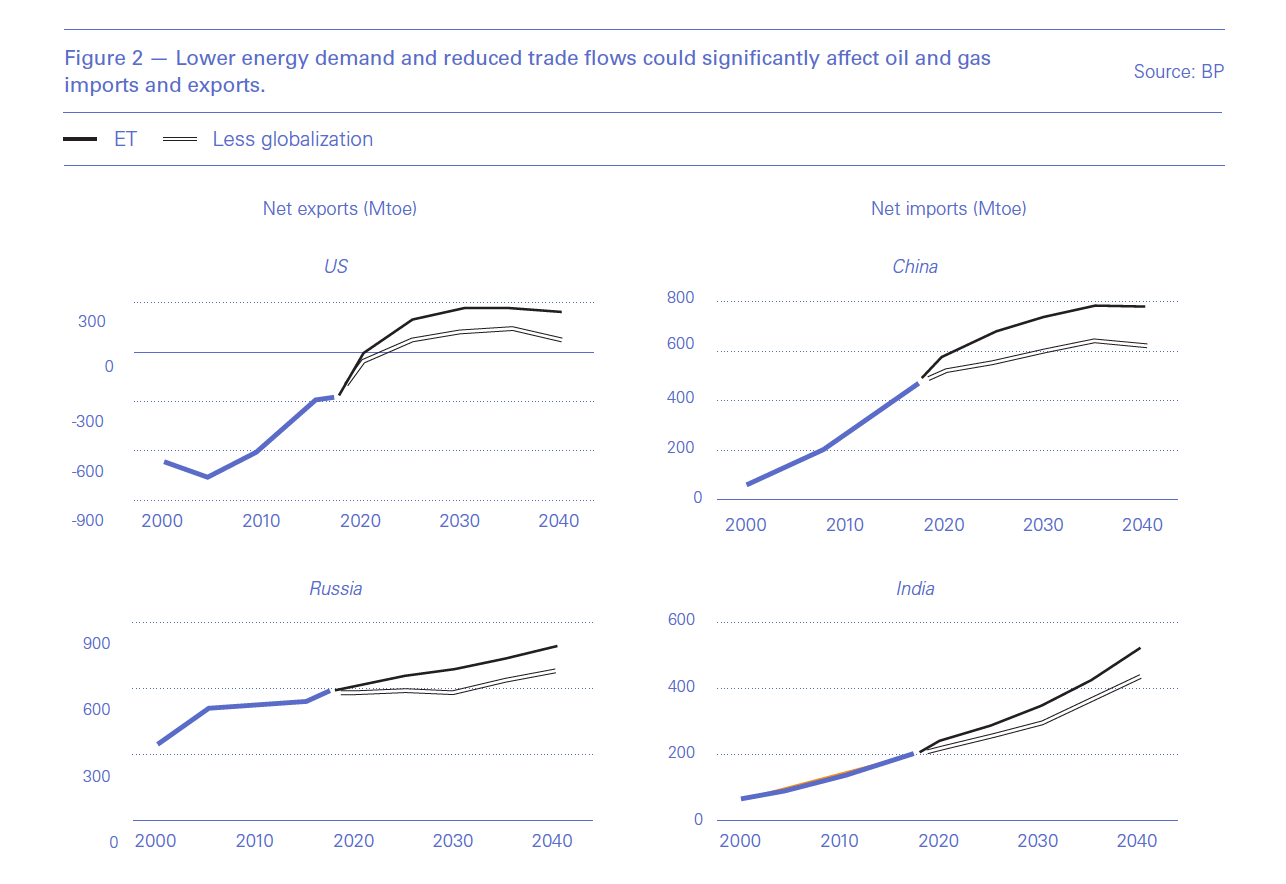

The lower level of energy demand, together with the increased concerns about energy security, would lead to a sharp reduction in energy trade, as overall demand would fall and countries revert to domestically-produced sources of energy, leading to less globalisation. This in turn would impact the largest exporters of oil and gas, such as Russia and the US (Figure 2), quite significantly.

The outlook points out that in terms of imports, the energy deficits of major importers of oil and gas, such as China and India, are smaller than in the ET scenario. China’s imports of oil and gas in the ‘Less globalization’ scenario are, respectively, 12% and 40% lower than in the ET scenario, with gas suffering more. This may provide some explanation about developing trends.

As BP’s group chief economist, Spencer Dale, said when presenting the outlook, such shifts can have lasting effects. The shock of the oil embargo instituted by Arab oil producers on the US in 1973, followed by the Iranian revolution in 1979, alerted oil consuming countries to the dangers of relying heavily on oil imports. This led to measures curbing dependence on oil, which subsequently became permanent.

With the US becoming increasingly willing to use its control of global financial systems, trade wars and sanctions as tools to protect what it sees as its vital interests, what would be the effect on global oil and gas markets?

US trade wars

In August 2017, President Trump ordered an investigation into Chinese trade policies and has been steadily imposing tariffs on Chinese goods since.

China considers itself to be a leading member of the developing world, but the chairman of Sinochem, one of China’s largest chemicals groups, said at Davos that trade tensions with the US have left the Chinese questioning their standing. China was shocked by the US trade war and sanctions, and the wider implications, becoming acutely aware of the potential dangers to its energy security.

Problems last year on gas pipelines linking the country to Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, which were due to equipment failures and cold weather, have added to these concerns.

As China has become the largest energy consumer in the world its energy import dependence has increased rapidly. It reached 45.3% last year, making it particularly vulnerable to such external threats.

China has been caught unprepared, having previously paid insufficient attention to such threats. This prompted China’s president Xi Jinping to call for a boost in national energy security in August, by reducing energy import dependence and increasing domestic energy output. The core of China's new energy strategy is to give a high priority to domestic supply and connectivity, develop diverse energy resources, and rely on energy efficiency and conservation.

In response to Xi’s call, China’s oil and gas majors, PetroChina, Cnooc and SinOpec embarked on an expansion programme this year, with a focus on natural gas production, including shale. This is leading to an 18% year on year increase in capital expenditure in 2019 to a record $77bn, the highest level of investment since 2014.

Launching PetroChina’s programme, CEO Wang Yilin went as far as to say: “We shall carry through resolutely the state council’s call on stepping up domestic exploration and development and launch an offensive war.”

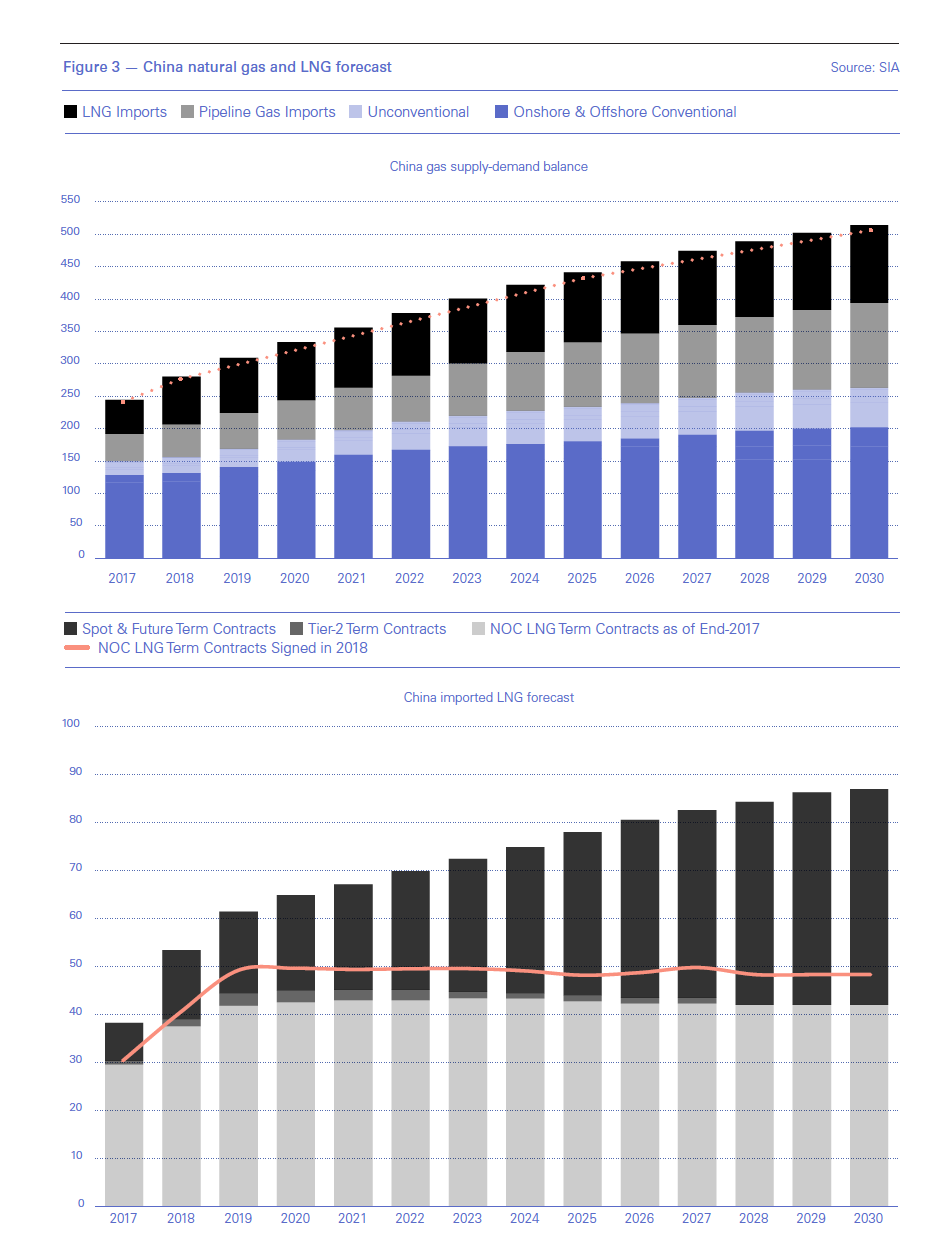

This renewed effort is expected to lead to an increase in natural gas production of 6-8%/yr to 2020. But this will not be enough to cover the expected increase in gas demand (Figure 3). Some of the shortfall is expected to be covered by increased pipeline imports from central Asia to China and the rest by LNG imports.

However, as a result of these developments, even though Chinese LNG demand is expected to continue rising in 2019, the pace of growth is expected to be slower, nearer 10%, down from a whopping 38% increase in 2018 and 50% in 2017. That’s still high, but not as high as during the previous two years, and does not yet reflect fully the impact of the trade war with the US and China’s slower economic growth.

Having woken-up to its gas import vulnerability, China is re-evaluating import dependence and energy security and reforms should be expected.

China has also developed a new energy security concept that calls for “mutually beneficial cooperation with other countries, diversified forms of development, and common energy security through co-ordination.”

Russia is seen as a potential long-term stable and reliable source of oil and gas for China. The first Russian-Chinese energy business forum, held in November 2018 in Beijing, stressed the significance of joint energy projects for the socio-economic development of Russia and China, including the joint energy project portfolio.

The Power of Siberia gas pipeline is expected to start operations in December and China is already showing increasing interest in more Russian pipeline gas imports, probably as a result of concerns about energy security. Chinese companies are also participating in Russia’s Yamal LNG, already delivering LNG to the country, with Arctic LNG-2 about to follow – despite US sanctions.

China has also extended energy co-operation to include neighbours Myanmar and Philippines. Its energy security also involves investment in oil and gas fields abroad and diversification of its energy suppliers.

In addition to taking measures to improve security of oil and gas supplies, China is also pursuing greater use of renewables, nuclear power, and clean coal. It is also a global leader in the adoption of electric vehicles.

Given the above threats, coal has gained in importance in terms of energy security. China plans to add more coal to its energy mix, and annual capacity additions could grow to 400mn tons by 2020, or about a tenth of its capacity.

In addition, according to BP’s Energy Outlook, the pace of growth in renewables capacity in China is unprecedented. It increased by 12% last year and China is now the world’s biggest investor in renewable energy.

In addition to contributing to China’s war on pollution, nuclear is becoming an important component of the country’s energy security. After a two-year pause, China approved four new nuclear reactors earlier this year. These facilities will come on top of the 45 plants in operation in 2018, and additional 18 already under construction. Nuclear is targeted to provide 8-10% of Chinese electricity by 2030, compared to 3.6% now.

However, in an about-turn to the Paris Agreement, China’s energy focus exhibits less concern about international pressure regarding its environmental policies. This places priority on ensuring continuing economic growth and continuing use of all energy fuels, including coal, while maintaining efforts to clean up air pollution in cities.

The government has relaxed environmental policies, and now makes little mention of carbon emissions and climate change. A clear indication of these changed priorities is a rise of 5.2% in coal production in 2018, with more to come. Coal-fired power generation rose by 6% despite carbon emissions going up by 2.5%.

But fixing the trade war may not necessarily signal the end of US-China problems. These run deeper, involving next generation technologies, national security, global leadership, and threaten to challenge bilateral relations for years to come.

As a result, the actions being taken by China to reduce external dependency and secure its future energy resources, either domestically or through ‘mutually beneficial co-operation’ with neighbours, may become permanent at the expense of fossil fuel imports, including LNG, much as pointed out by Dale.

US sanctions

Use of sanctions by the US as foreign policy tool is escalating. Sanctions on Iran and more recently on Venezuela are the latest additions.

Overturning the landmark agreement to lift sanctions on Iran, which was engineered by the Obama administration in 2015 with the co-operation of the EU and Russia and the support of China, the Trump administration re-imposed sanctions in 2018. Through these the US has the power to stop other countries buying Iranian oil. Eight countries have been given six-month wavers to continue some purchases, but these may not be renewed after they expire in May.

Europe has been trying to sidestep the re-applied sanctions but so far unsuccessfully due to the central role of the US financial system in the world economy, including oil trading.

More recently, the US imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s national oil company PDVSA to raise pressure on the president Nicolas Maduro to resign. Similarly to the Iran sanctions, these measures prevent companies from using the US financial system to do business with PDVSA.

Their immediate impact has been to cut Venezuela’s crude oil exports by 40%, and the effect is still growing. On March 22 the US treasury imposed additional sanctions on Venezuela's state-owned bank Banco de Desarrollo Economico y Social de Venezuela and four related financial institutions.

These sanctions, and the uncertainties they introduce, are disrupting global oil trading and energy flows. It is another factor causing countries with large reliance on energy imports to seek ways to limit this by increasing domestic energy production, often relying on coal, but also by increasing investments on renewables.

Potential US action against Opec

The US house judiciary committee passed the ‘No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels’, or NOpec, Act in February. This will now go for a vote before the full house of representatives. The intention of the bill is to make it illegal for foreign nations to work together to limit fossil fuel supplies and set prices and it is directed against Opec and its associates – chiefly Russia.

This is not new. The bill has been introduced in every Congress over the past 20 years. But given Trump’s criticism of Opec’s control over oil prices there is renewed momentum to get it passed, and it has bipartisan support.

Analysts at Barclays have said that the passage of the bill could make the oil market more unstable. “Overall, we believe that if such legislation moved forward, it would threaten the sustainability of the Opec and Opec+ grouping, add more volatility to the market, and make the perceived floor under prices even more fragile,” they warned.

Ironically, Opec's moderating role in maintaining stable oil prices is what has allowed the US oil sector to thrive, helping it to become a major oil and gas exporter. This prompted Opec secretary general Mohammed Barkindo to warn Congress: "The legislation as it stands would not serve the interests of the US.” Indeed, removing this role could lead to a ‘free-for-all’ situation bringing back oil surpluses and prices down to 2016 levels.

Given the close linkage between LNG and crude oil prices, any disruption is bound to affect global LNG supply and demand, particularly where the floor is removed from under oil pricing.

Energy security concerns

Clearly, global trade disputes, sanctions and threats – and uncertainties whether these will be imposed or once imposed will be lifted - increase concerns about energy security, causing countries to consider ways to reduce energy imports, favouring domestically-produced energy.

Even Japan’s 2030 Energy Plan is driven by energy security. It states that Japan needs to secure stable energy supplies to support economic activity and national security. It targets diversification of energy supplies and cutting the dependence on imports to a bare minimum.

Ever since the 1973 oil embargo, Japan has been very conscious of its vulnerability to energy import dependence and the importance of energy security. In addition, neighbouring China’s increasing strength and thirst for energy means Japan needs to limit risks to its energy supply.

That means diversification and limiting dependence on fossil fuel imports. This includes LNG imports, which are targeted to fall from 88.5mn mt/yr in 2015 to 62mn mt/yr by 2030. LNG imports last year fell to 82.8mn mt, the lowest since 2011. In LNG’s place, Japan is prioritising a return to nuclear energy, increasing renewable energy supplies – expected to provide up to 24% of the country’s energy mix by 2030 – and continued reliance on coal.

India has its own energy security concerns caused by China’s aggressive quest for energy in the south Asia region. Any external interruption of India’s energy supplies could threaten national security. Rapidly increasing energy prices are a threat to India’s economic and energy security.

As a result, India is looking to maximise domestic energy resources such as coal and renewables. Coupled with infrastructure limitations, these concerns are limiting growth in natural gas imports.

Following the downing of the Russian fighter plane in 2015 and concerns that Russia might cut-off natural gas supplies, Turkey’s 2030 Strategic Plan prioritises making greater use of domestic energy resources such as hydro, renewables and lignite in an effort to limit dependence on energy imports, such as natural gas.

These are just a few examples where threats to national energy security have led to policies, often enshrined in state energy strategies to become more self-reliant where energy is concerned.

Implications for natural gas

With Chinese economic growth slowing and the world economy following suite, protracted trade disputes may further undermine global demand for oil and gas. Opec’s Barkindo recently observed: “Any measures that may impact or constrain trade may likely impact on growth and by extension on demand for energy.”

As Figure 2 shows, the impact of ‘less globalisation’ resulting from trade disputes would be stronger on US oil and gas exports, which would be two-thirds lower than in the main BP Outlook ‘evolving transition’ scenario.

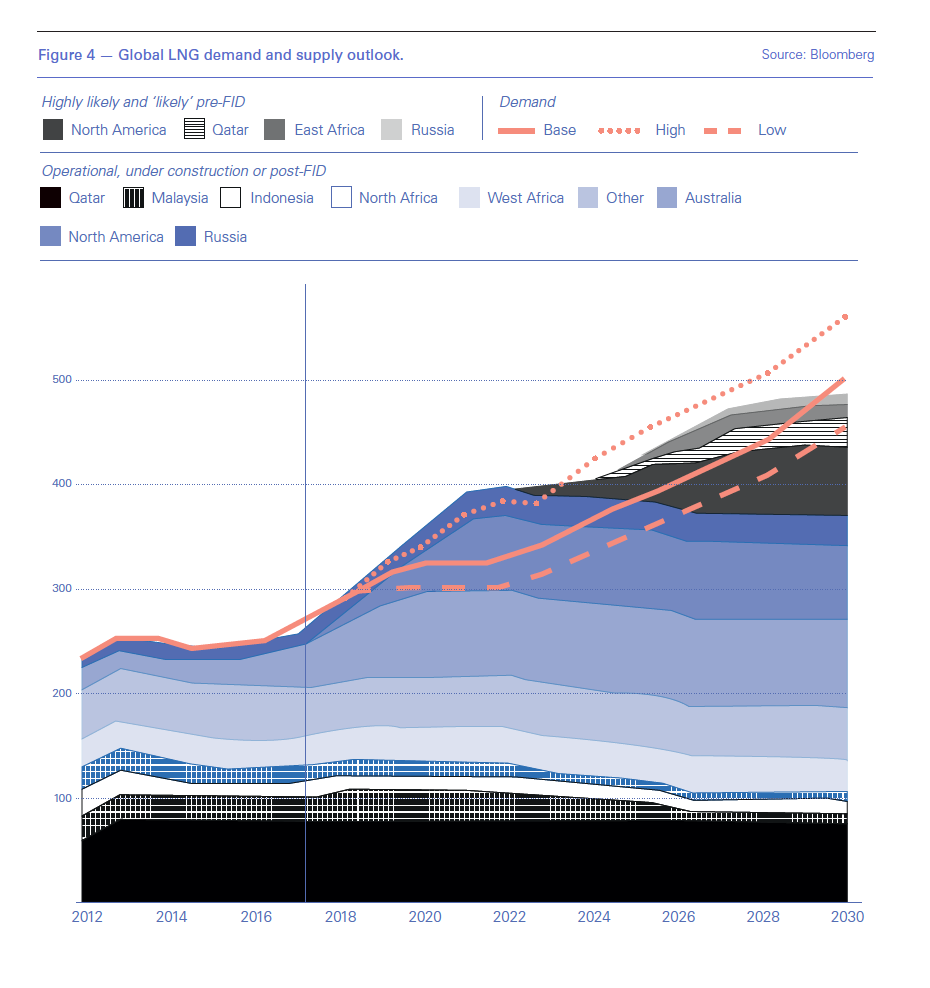

Once measures or deals are put in place, especially pipeline deals, as a result of trade wars or sanctions, the likelihood is that this effect will endure even after these threats are lifted. And this at a time when record new production of LNG is coming into the market and a substantial number of new projects are lining up for final investment decisions (FIDs) (Figure 4). LNG prices are already down owing to this and mild weather, and are expected to stay low well into 2019 and likely next year.

These trade disputes are already making it harder for US LNG exporters to beat Qatari and Russian gas sales to China. In fact CNPC has concluded that ongoing trade disputes are forcing China to move away from US LNG to other sources.

The result of prolonged disputes is that some of the proposed US LNG export terminals may struggle to secure sufficient sales to attract financing and may not proceed to FID.

There is a view that by early-2020s global demand for LNG will exceed supplies and prices will go up. But this assumes that demand growth will continue unabated, following recent trends (Figure 4).

This may prove to be optimistic should countries such as China, Japan, India and Turkey turn inwards and put in place long-term measures to maximize domestic production of energy in an effort to improve energy security. The outcome then could be that future demand is nearer the ‘base’ or even ‘low’ estimates in Figure 4, with a huge impact on future LNG projects and prices.