Turkey: Dispelling Unhelpful Myths

Last December’s announcement of Turkish Stream, a proposed 63 billion cubic metre pipeline that aims to bring Russian gas across the Black Sea into Turkey has elicited great interest from academics, analysts and journalists who felt impelled to propound opinions, or guess from the scant available information its odds of success.

Some of the views put forward suggested the deal would benefit Turkey, enhancing its leverage in Moscow and guaranteeing extra sources of gas at a time when Turkey’s gas demand is increasing.

The arguments may sound plausible to unsuspecting readers, but fail to square up with the reality. In fact, they are part of a wider web of myths that has been spun in recent years regarding Turkey’s ambitions as an energy hub and which, rather than help the country to act on its vision, is causing holding it back.

Myth and reality

A first myth depicts Turkey as a gas-hungry country.

While this may have been true between 1992-2012 when Turkey’s natural gas demand soared from 4.5billion cubic metres per year to 45.92bcm/year, thanks to the expansion of the gas distribution grid and economic growth, this is not the case now when consumption has been slowing down since 2012. [1]

As far as consumption forecasts go, although the incumbent BOTAS predicts an overall increase of 19 billion cubic metres on the current 50bcm/year annual consumption until 2020, Turkish gas distribution companies say this increase is more likely to be around 8bcm over the same period, driven by household demand. [2]

The slowdown in gas consumption mirrors a slowdown in GDP growth, which although reaching headline-grabbing levels of 9.2% in 2010 and 8.8% in 2011 has been on a sharp downward trend on the combined effect of weaker economic performance in the EU, its largest trading partner, and the exhaustion of growth avenues domestically.

Furthermore, the electricity sector, so far a driver of growth in natural gas demand since the beginning of the 2000s, is now one of the least likely to absorb volumes because of an increase in renewable capacity and a slowing economy, among others.

According to latest data from the Turkish regulator, EPDK, natural gas demand from the electricity sector saw a year-on-year increase of 0.84% in February this year, although winter months are typically the most critical in terms of gas consumption growth. [3]

A surge in renewable production (mostly hydro) has depressed the spot electricity price to such a level this year, that efficient gas-fired generation has been lying dormant, eerily mirroring the experience of Germany where gas-fired production has become an unprofitable business.

Ironically, despite suggestions in a recent article in Forbes that a widespread blackout at the end of March this year was caused by demand outstripping supply [4], the shutdown was triggered by a supply overhang in the east, which could not be cleared by evacuating the excess energy to the west where most gas-fired generation was switched off. [5]

Although demand figures are publicly available, very few commentators have proved perceptive enough to question the discrepancy between facts and the public discourse.

Even Elena Burmistrova, director general of Gazprom Export, the Gazprom subsidiary responsible for gas sales to Turkey, claims in the company’s May newsletter that Turkey’s natural gas demand would surge to 81bcm/year by the beginning of the next decade, stressing the need for increased volumes during the peak winter season. [6]

A presumed growth in Turkish gas demand would, of course, justify the need to bring in more volumes into the country from various regional sources, including Russia via Turkish Stream.

Based on her reading of the figures, Ms Burmistrova concludes that the building of Turkish Stream would be ‘not only desirable, but imperative for its [Turkey’s] energy security and the well-functioning of its energy-intensive economy.’ [7]

Less than a year since its announcement, Turkish Stream has already spawned vast quantities of literature, equaled perhaps only by those linked to its predecessor, South Stream which died an ignominious death at the hands of the EU keen to stymie Gazprom’s further forays in its eastern flank.

Turkish Stream myths

Three ‘sub-myths’ have already caught root regarding Turkish Stream.

Firstly, Ms Burmistrova, and other commentators argue that Turkish Stream is the response to Turkey’s gas demand growth.

A Gazprom press release of 7 May suggests that Turkish gas demand has increased over the past ten years, with Russian volumes pumped via Blue Stream, a pipeline across the Black Sea increasing by 4% in the first four months of 2014 compared to the same period last year. [8] The press release omits to mention that Russian flows into Turkey via the Trans-Balkan pipeline dropped year-on-year by 20% over the same period. [9]

The press release uses the gas demand data to justify the need for Turkish Stream whose first string is expected to be completed by the end of December 2016 and aims to bring 15.75bcm/year to the domestic market.

Of the 15.75bcm/year, only 1.75bcm/year will be in addition to what Turkey already gets via the Trans-Balkan pipeline annually. The remaining 14bcm/year transiting Ukraine, Romania and Bulgaria will be simply diverted through Turkish Stream.

The fact that Russia will supply less than 2bcm/year in addition to what it already does, suggests that Gazprom has fully understood the realities of the Turkish gas sector. Other arguments mooted last autumn that Russia would increase by 3bcm/year the capacity of Blue Stream, a 16bcm/year pipeline also carrying gas to Turkey across the Black Sea, have meanwhile fallen silent.

Secondly, Ms Burmistrova like many western journalists and researchers before her suggest Turkish Stream will not only enhance Turkey’s energy security, but also eliminate transit risks. [10]

They base their assumption on the fact that Turkey will be the first rather than the last recipient of gas along the transit route, averting geopolitical risks associated with the transit as seen since the Ukraine-Russia standoff.

Gas flow data preceding the announcement of Turkish Stream do not appear to back up those claims.

At the end of September 2014, Gazprom flows through Ukraine started to decrease on the transit pipelines heading west into Europe via Slovakia and south to Turkey via Romania and Bulgaria.

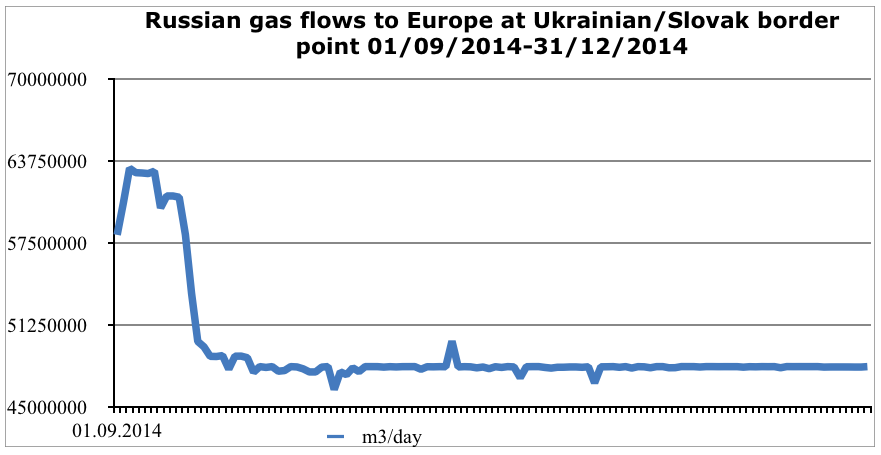

As shown in the two graphs below flows at the Velke Kapusany interconnection point between Ukraine and Slovakia fell from mid September and remained reduced until the end of 2014.

Source: Eurstream

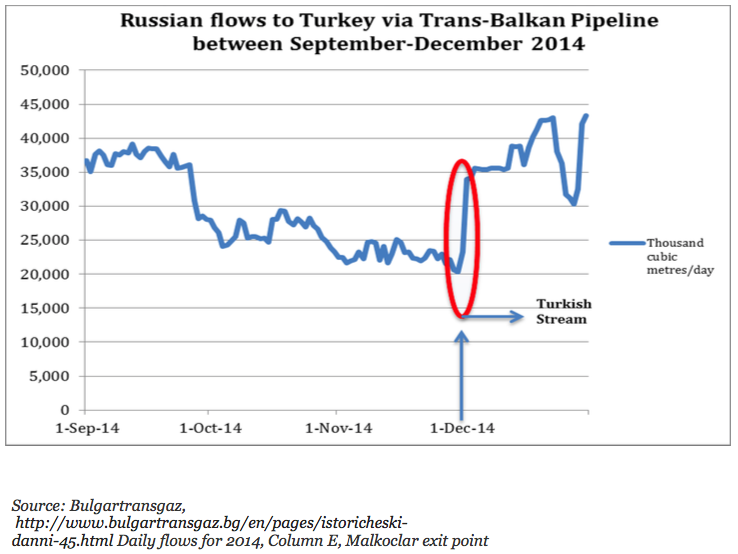

Flows on the Trans-Balkan pipeline to Turkey decreased from the beginning of October, dropped by nearly half by the end of November, only to surge back to normal contractual volumes within the first days of December.

Gazprom said at the time that the reductions in both pipelines, which peel off from the Soyuz trunk line in eastern Ukraine close to the city of Kharkiv, were linked and of a technical nature.

No further details were given. However if the flow reduction in both pipelines was linked, how come exports to Turkey surged back to near normal levels within the first three days of President Putin’s visit to Ankara and his announcement of the Turkish Stream project while those on the transit line heading to Slovakia continued to stay low?

To grasp the meaning of the gas flow reduction to Turkey in the two months preceding the Turkish Stream announcement, it is important to understand its impact on the wider Turkish gas sector.

Under normal circumstances Turkey receives an average 42 million cubic metres (mcm)/day of Russian gas via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline at its western entry point of Malkoclar on the Bulgarian border.

However, by the last day of November, imports had dropped to 20.3mcm/day, having induced confusion and panic among Turkey’s government and private natural gas companies who feared extensive blackouts during the winter months. Their fears were entirely justified.

Although nearly two-thirds of Turkey’s energy consumption is concentrated in the north-western Marmara region, the area is heavily dependent on Russian gas shipped via the Trans-Balkan pipeline.

Additional sources come from Turkey’s sole storage facility located in this area and two receiving terminals for liquefied natural gas (LNG). These sources complement the Russian pipeline volumes, but are not sufficient to replace them in case of Russian curtailments.

Any further volumes from Iran and Azerbaijan or from Russia via Blue Stream cannot move easily from east to west because of technical constraints in the Turkish transmission system.

In a nutshell, without Russian gas via the Trans-Balkan pipeline to the north-western region, Turkey’s energy security and, implicitly, its economy are at risk.

When Russian volumes started to drop dramatically in October and November, the Turkish government and private energy companies feared that Turkey was heading towards a crisis, particularly as winter was approaching and there were not enough supplies to cover peak demand.

Despite indications that the government had sought to buy more LNG than last year, ramp up hydro production to compensate for expected drops in thermal generation, or store more gas, they were hamstrung by the technical limitations of the system.

By the 1st December 2015 when Vladimir Putin arrived in Ankara, Turkey’s private and public gas companies were already on high alert.

However, within two days of Mr Putin’s visit to Turkey and Ankara’s decision to partner up in the Turkish Stream project, Russian exports to the Marmara region increased by 13mcm/day and by mid December reached their normal daily average of 42mcm/day.

There is no evidence to suggest that Gazprom had deliberately reduced the flows into Turkey in order to pressure the Turkish government into signing the Turkish Stream Memorandum of Understanding (MoU).

However, whatever the political maneuvering behind the Turkish Stream announcement, it is clear that the Turkish government could not take the risk of any major energy shutdowns just months away from parliamentary elections in June.

Greater leverage

A third sub-myth linked to Turkish Stream and regularly quoted by Turkish and western journalists argues that Turkey’s partnership in the project will give it greater leverage in Moscow. [11]

Few actually realise the pain that BOTAS and private importers have been going through over the last four months when Russia refused to grant discounts on import prices.

Gazprom has quoted a price to private importers that was more than $70.00/1000sm3 higher than the regulated tariff, pushing the entire sector on the verge of bankruptcy. A compromise was eventually reached, but only after four months of intense bargaining.

Meanwhile, the much-touted 10.25% discount on the oil-indexed import price offered to BOTAS was still not accepted by the latter at the end of April. Discussions have also dragged on over the application of the discount on the coefficient that modifies the oil formula or on the overall import price, which would not be as attractive to Turkey. [12]

Claims that Turkey’s security of supply is greatly enhanced once the Ukraine political risk is eliminated when gas flows are diverted across the Black Sea presuppose a smooth relationship between Ankara and Moscow.

Although Ankara’s reaction regarding Russia’s annexation of Crimea, or the 2008 war in Georgia was muted in the aftermath of the events, [13] Turkey has in recent weeks stepped up its criticism of Russia particularly following Moscow’s recognition of a so-called Turkish ‘genocide’ against Armenia.

In a very strongly-worded statement, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs said: ‘Taking into account the mass atrocities and exiles in Caucasus, in the Central Asia and Eastern Europe committed by Russia for a century; collective punishment methods such as Holodomor [also known as the Famine Genocide against Ukraine in 1932-1933] as well as inhumane practices especially against Turkish and Muslim people in Russia’s own history, we consider that Russia is best-suited to know what exactly ‘genocide’ and its legal dimensions are.” [14]

It is hard to believe that such accusations will contribute to the win-win relations mentioned by Ms Burmistrova in her May newsletter comment and ultimately guarantee the smooth flow of Russian gas exports to Turkey now and in the future.

The energy hub

The third myth relates to Turkey’s ambition of becoming an energy hub. The concept has been bandied about in the Turkish and foreign press and specialist literature, without any clear definitions of what it actually means or how it will be achieved. The notion is interchangeably used either to describe Turkey as an energy corridor or as a traded hub. [15]

Ms Burmistrova maintains that Turkish Stream will help Turkey to ‘evolve into a regional hub’, turning Turkey into a global crossroads for gas supplies.

Firstly, it is not even clear whether Turkish Stream will have any Turkish involvement.

In fact, press reports suggest that the Italian firm Saipem is building the offshore section. It is not known who will be building the shorter onshore section. [16] However, it is hard to imagine that Turkey would have considerable weight in a project that will carry exclusively Russian gas, the greatest part of the infrastructure, if not all, will be built by non-Turkish companies and the pricing of volumes would arguably mirror Russian interests.

If, however, Ms Burmistrova meant that Turkey would be a corridor for the transit of multiple gas sources, then, of course, she merely reiterates a geographical fact, which, in her own words, places ‘Turkey on the edge of both Europe and Asia.’

A stream of words

Repeating a series of myths about Turkey’s natural gas sector in total disregard of facts and figures that tell a different story will not only obfuscate the reality, but also misguide any decisions and policies that will be taken in the future.

Gutta cavat lapidem, non vi, sed saepe cadendo – a water drop hollows a stone not by force, but by falling often. Ovid’s words are as true in this context as they were 2,000 years ago.

There is an acute need for fresh thinking in Turkey. The country should be encouraged to pursue its energy hub ambitions in a way that not only recognises its centrality within a nexus of transit routes from east to west, but also enhances that position through a series of policies that break the grip of any one supplier onto its market. Turkey’s energy hub ambitions square up with its political vision to expand its influence regionally. However, such a project needs to be unencumbered by regional political diktats.

Turkey has to face up to its economic realities and adapt to emerging challenges. Its falling gas demand at a time when more natural gas volumes are expected to come from the Caspian Sea and northern Iraq should be seen as an opportunity to finally open up its borders and encourage the trading of the gas surplus that is likely to build up.

Finally, those who truly care about Turkey will know that only a cold-headed vision based on facts and figures and a healthy dose of honesty will help it to achieve its ambitions.

Aura Sabadus specializes in Turkey’s energy sector

[1] Winrow G., (2013) “The Southern Gas Corridor and Turkey’s Role as an Energy Transit State and Energy Hub,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 15 Nr 1

[2] Interviews conducted by author with Gazbir, the Turkish gas distribution association

[3] EPDK February 2015 report (last accessed 17 May 2015) http://www.epdk.org.tr/index.php/dogalgaz-piyasasi/yayinlar-raporlar/12-icerik/dogalgaz-icerik/1817-ddb-aylik-yayinlar-raporlar

[4] ‘From Russia with love: The Moscow-Ankara energy affair” (last accessed 15 May 2015) http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2015/05/13/from-russia-with-love-the-moscow-ankara-energy-affair/

[5] Author’s interview with the grid operator TEIAS, April 2015

[6] Gazprom Export May newsletter (last accessed 15 May 2015) http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/presscenter/publications/

[7] Ibid.

[8] Gazprom Export http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/presscenter/

[9] Bulgartransgaz, current daily flows information (Column E, Malkoclar) http://www.bulgartransgaz.bg/en/pages/kapacitet1-98.html

[10] Stern J., Pirani S., Yafimava K., “Does the cancellation of South Stream signal a fundamental change in Russia’s gas export policy? Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (OIES), January 2015 http://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Does-cancellation-of-South-Stream-signal-a-fundamental-reorientation-of-Russian-gas-export-policy-GPC-5.pdf (last accessed 30 April 2015) see also Buckley, N., ‘Turkish pipeline a sign of Gazprom getting real with EU partners’ Financial Times, 18 February 2015 http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/eedfa430-b764-11e4-8807-00144feab7de.html#axzz3aPOb1gDX (last accessed 30 April 2015)

[11] OIES op.cit. for example

[12] According to interviews conducted by the author

[13] Cagaptay S., Jeffrey J., ‘Turkey’s muted reaction to the Crimean crisis’ 4 March 2014 http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/turkeys-muted-reaction-to-the-crimean-crisis

[14] ‘Press release regarding the approach of the Russian Federation on the 1915 events, MFA Turkey, 24 April 2015 http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-129_-24-april-2015_-press-release-regarding-the-approach-of-the-russian-federation-on-the-1915-events.en.mfa (last accessed 17 May 2015)

[15] Gazprom Export newsletter

[16] ‘Saipem in pole position to win Turkish Stream contracts – sources ‘http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/04/14/saipem-gazprom-turkishstream-idUKL5N0XB3DD20150414