Turkey’s difficult balancing act [NGW Magazine]

The commissioning in January of the twin strings of Russia's TurkStream gas export line through Turkey was supposed to serve both countries. It would prevent Ukraine from taking gas destined for the Balkans and Turkey and allow Moscow to pressure Kiev, while also cementing the alliance forged between Moscow and Ankara in the wake of the failed Turkish military coup of 2016.

However as recent events in Syria have confirmed, relations are far from smooth and the two remains at serious loggerheads over a number of issues, not least over Russia's natural gas exports to Turkey – or more accurately, Turkey’s failure to buy the contracted volumes.

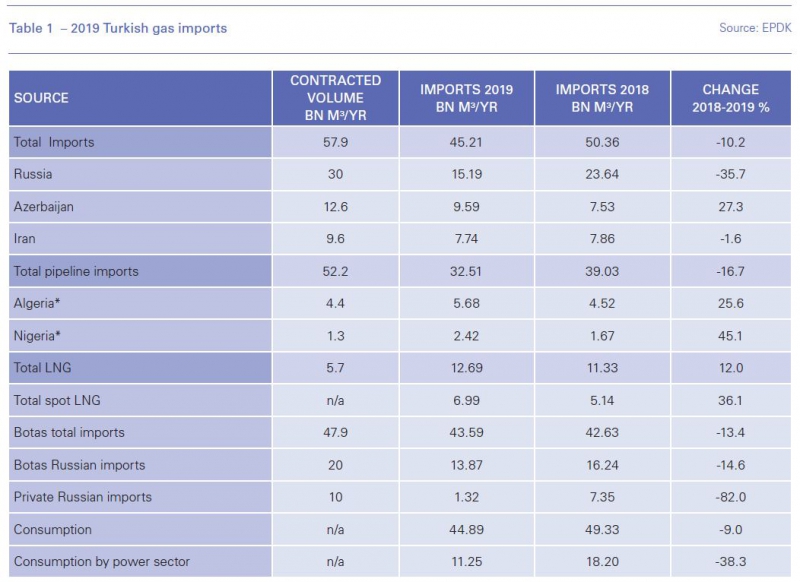

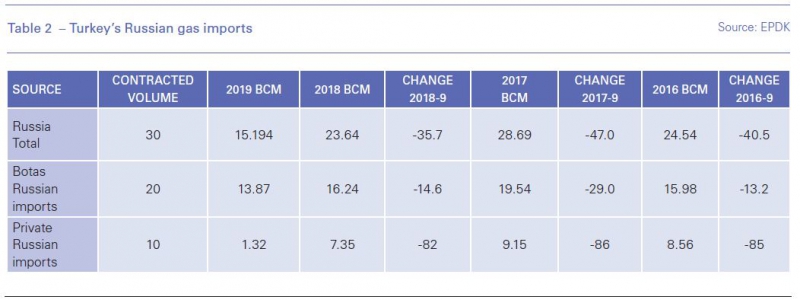

According to official Turkish data published last month, Turkey's Russian imports last year totalled only 15.194bn m³, a little over half the contracted volumes, down 35.7 % on 2018, and down 47% on 2017. Of this, the 13.87bn m³ imported by state Botas was only 69% of what had been contracted; while the 1.32bn m³ imported by the seven private importers represented only 13.2% of their take or pay contracts.

This is despite Turkey's total imports last year dropping by only 10.2%. Excluding a slight fall in Iranian pipeline volumes, imports from Turkey's other suppliers, Azerbaijan, Algeria and Nigeria, all rose. Indeed, volumes from Algeria and Nigeria were both well above contracted levels. Low prices would have made LNG more attractive and deliveries were up 36.1% on 2018. Accounting for 15.5% of total imports, they were only marginally less than Russian volumes.

With the sharp rise in Azeri volumes reflects the ongoing ramp up in imports through the TransAnatolian Pipeline (Tanap) pipeline commissioned in 2018, the picture is clearly one of Turkey meeting its take or pay commitments to all long term suppliers with the exception of Russia and supplementing any shortfall with spot LNG, almost all of it imported by state gas importer Botas.

Growing problem

The problem is not new. Turkey's Russian imports have been falling since Q2 2018 when a faltering economy compounded by a major spat with the US hit the lira hard. Turkey's current account deficit spiralled downwards and pushed Ankara to double down on efforts to reduce dollar-denominated gas consumption.

Ankara hiked by 49.5% the price state importer Botas charged gas plants for power, a tactic it could allow itself as it high levels in Turkey's main hydro dams and successive mild winters left it with spare capacity. Power prices on Turkey's EPIAS power market fell sharply, leaving the operators of combined-cycle gas turbines unable to generate at a profit.

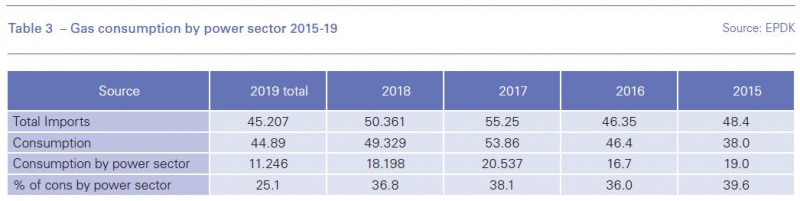

As a result the percentage of gas consumption by the Turkish power sector fell from 38.1% in 2017 to only 25.1% last year, with the fall being borne almost exclusively by the fall in Russian imports.

At the same time Botas was able to import increased volumes of cheap spot LNG to subsidise sales to other consumers, undercutting the private importers, leaving them unable meet their take or pay commitments of their contracts with Gazprom.

Although the problem became clear from the monthly data published by Turkey's energy regulator EPDK, neither Ankara nor Moscow made any comment on the issue.

Rumours suggested both that Moscow was willing to let the issue slide in return for the January commissioning of both 15.75bn m³/yr strings of the TurkStream pipeline, but also that Moscow was pressing for Botas to take over some or all of the seven private importers and assume responsibility for their debts of which Ankara was offering to pay only a portion.

Public acknowledgement - changing market

Only since the commissioning of TurkStream in January has there been a significant comment on the problem, with deputy Turkish energy minister Alpaslan Bayraktar confirming in a conference by influential US think tank, The Atlantic Council, that Turkey is using the easy availability of cheap spot LNG to pressure its gas suppliers, including Russia, saying that "they have to be flexible".

Bayraktar confirmed that he was referring both to ongoing talks with Russia, over contracts for 8bn m³/yr; with Azerbaijan for 6.6bn m³/yr; and Nigeria for 1.3bn m³/yr of LNG all of which time out by the end of 2022.

But the message clearly applies also to contracts with Algeria for 4.4bn m³/yr of LNG which runs to 2024, with Russia for 16bn m³/yr through the Blue Stream pipeline which times out at the end of 2025 and with Iran for 9.6bn m³/yr of pipeline gas which runs to mid 2025.

However his comments also only serve to highlight that with the exception of a small reduction in gas from Iran, last year saw Turkey meet or exceed contracted volumes with all suppliers with the sole exception of Russia. This suggests that Ankara is employing radically different tactics in talks with Russia than it is with its other suppliers.

Given the nature of the spot LNG markets, negotiations with Algeria and Nigeria likely focus on volume and commitment rather than price, with both having last year supplied spot cargoes in addition to contracted volumes. The more so given that the Covid-19 crisis has already impacted Chinese demand and any wider global economic impact can only further dampen demand and further reduce prices.

Talks with Azerbaijan by contrast will likely start from the mantra of "one nation two states", employed by the leaders of both to indicate their deep-seated historical, cultural and linguistic ties. But they will also take into account the fact that Turkish upstream operator TPAO holds an 18.9% stake in the Shah Deniz gas field that provides most of Baku's export gas, while Botas holds a 30% stake in Tanap, through which Baku will transit its exports to Turkey and Europe.

Similarly, even some of Turkey's other spot LNG imports have a political dimension. Political ties have been close for some years with the Qatari royal family being major investors in the Turkish economy, and became closer after Saudi Arabia and UAE broke off diplomatic relations with Doha in 2017. This resulted in Ankara fast-tracking the establishment of a military base in Qatar.

Having become a major supplier of spot LNG through a series of unpublished purchase agreements, Qatar gas exports to Turkey have risen steadily, only falling last year following a brief suspension during talks on a new purchase agreement. All of which serves to highlight that while political relations may also impact Turkey's gas imports from other countries, they do so in a different manner to Turkey's Russian imports.

What now?

How long the current gas issue can continue unresolved is unclear. News in early March Gazprom had agreed to slash by the price it charges Bulgaria for gas by 40.3%, and to switch from oil indexed pricing to hub indexed – a key requirement of the anti-trust decision reached by the European Commission – should suggest that Moscow is willing to do the same for Turkey. Especially as Bulgaria is now receiving its gas via Turkey, through the TurkStream pipeline which Moscow delivered, as promised, on time.

Similarly news that Saudi Arabia is prepared to boost output and force down the crude prices against which Turkey's Russian gas imports are indexed should provide further incentive to Moscow to cut a deal. And at the same time the fact that contracts for 8bn m³/yr of Russian gas, out of the 14bn m³/yr delivered to Turkey via TurkStream will time out shortly, with another 16bn m³/yr ending in four years should provide some incentive for both sides to reach an agreement.

However given that the combined debts of Turkey's seven private importers are reckoned to total over $2bn, on top of any debts run up by Botas, any agreement is unlikely to be a simple matter of an agreed price reduction.

While Ankara has succeeded in boosting its LNG import capacity to the extent that it has been able to cope with lower Russian volumes so far, lowering Turkey's gas import bill by substituting LNG for all Russian volumes is not an option. A worst-case scenario of Russia suspending or cutting exports to Turkey to force its own terms would have a serious impact, especially if it coincided with one of the perennial drought years which cause Turkey's hydro power output to fall sharply.

Turkey's current generation over-capacity is expected to continue as new coal and renewables capacity comes online, but with electricity demand also expected to continue growing, this will not last forever. With considerable gas-fired turbines standing idle, gas for power is expected to make a come-back, the only question appearing to be the speed with which a new balance can be achieved that allows both importers and power plant operators to make a profit.

_f1920x300q80.jpg)