Turkey’s gas hub aspirations [Gas in Transition]

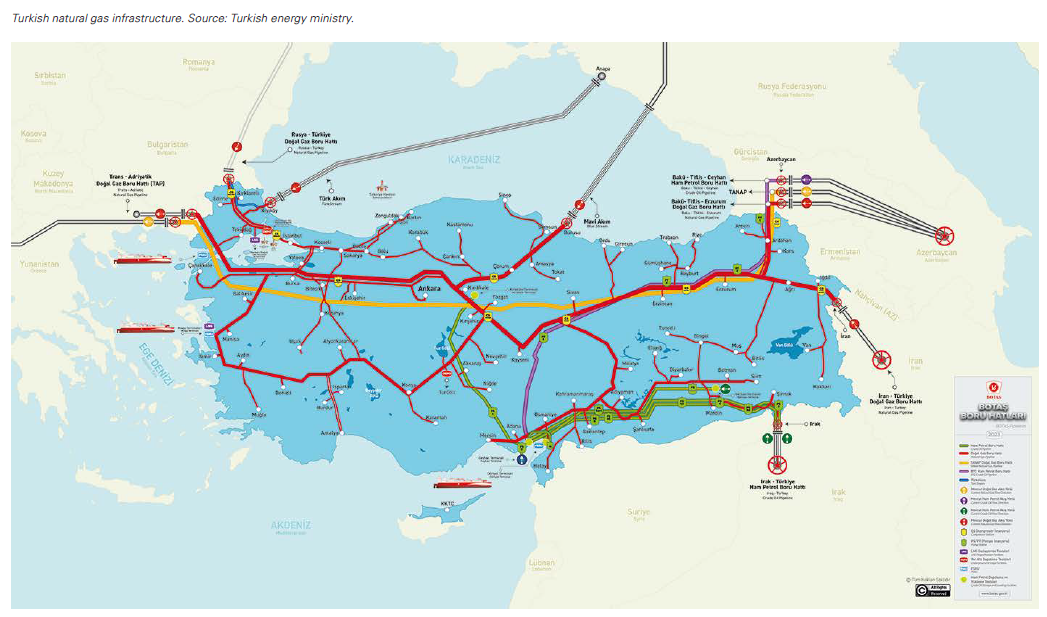

Turkey has for more than two decades sought to make itself an important player in the international energy industry. While it has little hydrocarbon resources of its own, the country is strategically located between major Western markets and major energy producers in the Middle East and Russia. Over the years an extensive pipeline system has taken shape in the country that imports oil and gas from Russia, the Caspian, Iran and Iraq, and distributes them to domestic power generation markets and refineries. Gas pipelines also extend into western Turkey from where they stretch into Greece and the Balkans, carrying Azeri and Russian gas.

Turkey is already taking steps towards the role of being a regional distributor. In the last month the Turkish pipeline company Botas has signed agreements to ship gas by pipeline to Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Moldova.

Turkey also has three LNG import terminals that import gas for domestic needs, but which can also be re-exported to European customers.

In the early 2000s, when considerable attention was being paid to the volumes of oil and gas that were expected to be produced in the former Soviet states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, Turkey was speaking of developing a “Rotterdam on the Med” that would be located at the East Mediterranean port of Ceyhan, where there was to be an oil and gas entrepot that would be the terminus of oil and gas pipelines from across the region and deliver feedstock to loading terminals, refineries and LNG export facilities.

That idea eventually faded as the vast quantities expected from the Caspian did not materialise and producers opted for export routes more simple and less costly. But two major projects involving Turkey did result from the Caspian resources: the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline (which does ship oil from Ceyhan) and the Southern Gas Corridor, which runs from the Azeri capital Baku, across Georgia, Turkey, Greece and Albania to Italy and which includes the long trans-Turkey section, the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP). The large exports of Kazakh oil found their way to Russia’s Novorossiysk port on the Black Sea.

There were other projects on the drawing board that involved Turkey, most notable was Russia’s South Stream gas pipeline, which proposed to transport gas from southern Russia across the Black Sea by subsea pipeline to Bulgaria, as the Blue Stream pipeline transports Russian gas to northern Turkey.

Moscow was forced to drop the project when its demand to override EU rules on pipeline operations was refused by the European Commission. Russian President Vladimir Putin then announced TurkStream, which is now operational and delivers gas to the European side of Turkey, from where it can be extended into Southeast Europe. Dual pipelines make up TurkStream, one that delivers 15.75bn m3/year to Turkey, and a second, which can deliver the same amount to Europe.

New Russian route to Europe

Convinced that Russian gas will someday have a post-Ukraine war future in Europe, Putin has encouraged Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to pursue the idea of creating an international gas hub with the intent of Russian gas playing a major role. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resulted in the EU losing most of its Russian pipeline gas, on the Kremlin’s behest. But in any case, the EU is striving to eliminate all remaining imports within the next few years. Furthermore, the unexplained bombing of the Nord Stream gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea last year has for now sealed the fate of Russian gas to Europe via a northern route – without major reconstruction work and investment.

A year ago, when the actions taken against Russian oil and gas by the West began to bite, Putin suggested to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan that Turkey be the location of a natural gas hub, an ideal that fits well with Erdogan’s own ambitions. The idea went back and forth, but during a recent gathering in Ankara of the ruling AKP party, Erdogan said he and Putin have agreed on moving forward with the gas hub. By agreeing with Putin to create a gas hub, Erdogan said, Turkey had secured a vital opportunity.

“European countries are currently searching to find where to get natural gas supplies," he said. "Thank God Turkey does not have such a problem. Hopefully, we will soon become a hub for natural gas.”

The idea sits well for Russia too. With gas entering Turkey from a number of sources, the hub would not be able to distinguish the origin of the gas, thus enabling Moscow to move its methane molecules into EU markets that are trying to avoid Russia energy supplies.

Vital Russian supplies

Energy relations with Russia are considered to be vitally important for Turkey. The country must import about 90% of its energy needs and it is estimated that it gets a third of its oil and petroleum products from Russia, while the total capacity of Blue Stream and TurkStream amount to about 45bn m3/yr. With a surplus of gas, Russia is keen to sell more gas to Turkey that could ultimately be moved into Europe and thus circumvent EU plans to boycott Russian gas and eventually end its import altogether.

“First of all, we are talking about creating an electronic platform for gas trading to the European continent,” Putin stated in Moscow recently. “Everyone is interested in this: both our Turkish friends and us, but also everyone who wants to buy our resources on the European continent.”

The Russian leader insisted that there are European states looking to purchase Russian gas, saying that Russia continues to supply them through the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines.

The Russian leader insisted that there are European states looking to purchase Russian gas, saying that Russia continues to supply them through the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines.

“[Those gas pipelines] are working efficiently, fully filled,” Putin said. “In principle, we have ideas to expand these opportunities. But I repeat: the first stage is the creation of an electronic trading platform. We do not see any big problems in its creation: Turkey is interested, we are also interested,” he said, adding that Russian and Turkish ally Azerbaijan may get involved in the project.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak stated recently that Russian state-owned gas company Gazprom and Botas had outlined a roadmap for the project and that the governments of both states are now studying it.

“Establishing an electronic trading platform would be suitable, especially for Europe and Southeast Europe, to determine gas prices based on the volumes to be sold there,” he said, adding that the two countries are expected to approve the plan soon so that implementation could begin.

During the recent ADIPEC energy conference in Abu Dhabi, Turkish Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar noted that the gas shipments now going from Turkey to the European states of Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Moldova, Turkey is “becoming more and more of a hub for natural gas.”

Gathering the region

Turkey receives a steady flow of gas from Russia and Azerbaijan and from LNG terminals at Marmara Ereglisi onshore, and at FSRUs at Aliaga and Dortyol. A pipeline delivers gas from Iran, but shipments can be sporadic, and while Turkey has discussed gas deliveries from the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq, they are not expected to begin soon.

President Erdogan, who has been in a reconciliatory mood since his reelection in May, spoke recently with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu about energy cooperation between the two states in the East Mediterranean. The Turkish energy minister was making plans to visit Israel to make the rapprochement official, but the attack by Hamas on southern Israel has interrupted those plans.

Turkey has for the last decade been keen to have Israeli gas piped to Turkey with the promise that it would be shipped on to Europe. Israel, which just last year began to export small volumes of gas to Egypt, has entertained this proposal before, but never committed. Currently, Israel is deep in energy cooperation with Cyprus and Greece, and the war with Hamas will have to be over before any further talks on the export of East Mediterranean gas goes further.

Indeed, Turkey occupies a strategic location that could be beneficial for gas shipment logistics, but it has become clear since the war in Ukraine that Europe is reluctant about obtaining too much gas from one source, as a hub in Turkey might become. Furthermore, Turkey’s main partner in this endeavour is a country that is working to subvert European guidelines and take over an independent European country.

All in all, Turkey may succeed in setting up a platform to trade ‘Turkish’ gas, but the project will certainly gain the attention of the EU, and even those countries that are receiving gas through Turkey now, may eventually find the deal not all that attractive.

In mid-October, Bulgaria, which does not buy Russian gas, imposed a transit tax of some €10 for every MWh of Russian gas that is transported through the Bulgaria gas network to Serbia and Hungary.

According to a report in European Views, Bulgaria is not trying to make gas prices higher for Serbia and Hungary, it just wants to make it less profitable for Gazprom to transit gas through Bulgaria. The Russian gas is transported through TurkStream to western Turkey and then to the Bulgarian border and on to Serbia and Hungary.

The two countries were reported to be alarmed by Bulgaria’s decision, which as one commentator said is designed to make Serbia and Hungary look elsewhere for gas supplies. The new rules call for fines of between $10,750 and $54,000 for firms that do not pay the tax by the end of each month.

Such a situation poses the question of whether this duty will be factored into prices quoted on the planned trading platform.