UK producers prepare to take a pounding [NGW Magazine]

No sooner had the UK upstream industry recovered from the last precipitous drop in prices and become familiar with the phrase ‘lower for longer’, than another, much bloodier, one comes along.

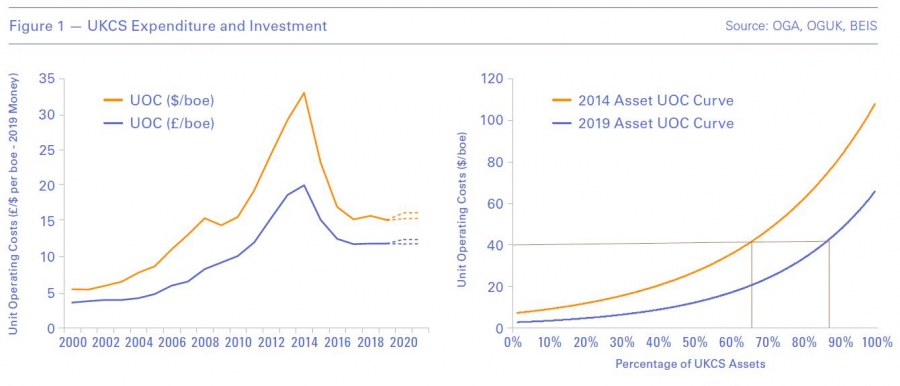

Across the UKCS overall, unit operating costs (UOCs) averaged $15.20/boe (£12.50) in 2019. This compares with 2014 when average UOCs were $32/boe (£20/boe). The upstream industry group Oil & Gas UK (OGUK) estimates that around 85% of assets which produced at least 1mn boe last year have UOCs under $40/boe, compared with two-thirds in 2014 (Figure 1).

The improved cost profile has been achieved through reductions in operating expenditure and increased production: last year the UK industry produced 20% more, and at a 30% lower cost than in 2014. The highest-cost asset in this group is now around $64/boe, compared with more than $100/boe in 2014, OGUK said in its Business Outlook 2020, published in March.

But this time the drop is not only lower and sharper; it is also accompanied by an infectious and possibly fatal illness that risks making close-quarters work on rigs and so on all but impossible. Several partial evacuations have taken place, slowing down work programmes unpredictably.

Private equity which poured into the basin over the last five years to snap up missed opportunities to create Chrysaor, Siccar Point, Zennor, Neptune and others will now be wondering what their exit strategy is to be, recalling the joke that a long-term investment is just a short-term investment that somehow went wrong. The original horizon had been about five-seven years to acquire, operate, build and exit.

According to Wood Mackenzie, the last round of cost-cutting means that 95% of onstream production is ‘in the money’ at $30/b. "But close to a quarter of fields will run at a loss in this price environment. The major concern here is not volumes. Early shut-ins would accelerate $20bn in decommissioning spend."

The complex web of offshore pipelines has to be kept intact if one party’s platform decommissioning is not to trigger a domino effect of premature closures at platforms further upstream, trapping billions of dollars of value.

Militating against that nationally strategic priority are individual companies’ needs to slash operational expenditure in the short term. But over the longer term they will need to keep investing in order to ramp up production and reduce unit costs, WoodMac said. "If the industry goes into harvest mode, a premature end is inevitable," it said.

However, short-cycle, strategic tie-backs are still likely to go ahead. About 3bn of the 6bn barrels of economically viable resources break even below $50/b; further cost reductions or a price recovery could quickly make them viable again, it said.

The outlook is more positive in Norway, where more than 60% of investment comes from locally-focused players with strong balance sheets, WoodMac noted. But the recent wave of FIDs cover projects which need Brent at $40/b to generate positive cash flow.

But in both jurisdictions where governments could intervene, there is the counteracting pressure from social groups who are keen to stop subsidies for oil and gas production.

"At a time when there is public pressure to move towards more a 'greener' energy mix, it’s hard to see governments easing the fiscal terms," said Wood Mackenzie. "Long term, the energy transition needs to accelerate but there’s a risk of short-term stagnation. For the companies that survive, they will need to adapt to a greener future."

|

A tale of two minnows Small companies, relatively speaking, such as Independent Oil & Gas (IOG) working in the southern basin and where there is an old gas pipeline to shore already in place, might be safe for now. Its share price at press time was little changed from where it had been January 1: £0.136/share compared with £0.156. But cashflow is still to come. On the other hand, new entrants such as RockRose, which picked up assets such as Marathon’s Brae fields, were designed to work in a low-price environment when it listed on the stock exchange four years ago. In an unusually perky note late March, it said it was "well positioned, despite current oil market uncertainties" to cope with the present market situation. Its oil and gas output hedged, it has no debt and it has £287mn ($340mn) of cash. It had tried to buy IOG last year but the target sorted out its finances in time. Brent crude traded below $30/b when RockRose was set up and it says it has remained focused on being able to operate in a low oil price environment. It expects unit operating costs of around $30/barrel of oil equivalent (boe) this year. RockRose hedged 455,000 barrels of oil at $65.70/b for Q1 2020 and 63mn therms of gas at 49p/therm for calendar 2020, both at prices well above the forward curve: the next three quarters of this year are assessed at about 25 p/therm. Looking further ahead, an additional 54mn therms have been hedged in each of 2021 and 2022 at 38p and 42p respectively. Its capital expenditure for this year was to have been about $200mn, with much of that earmarked for the development of the Shell-operated Arran gas/condensate field. However, other discretionary spending is being reviewed and it is anticipated that at least $50mn of this capital expenditure will be deferred, a drop of 25% and in line with other businesses, it said. |

|

Tide of takeovers? A partner at energy law firm Bracewell UK, Alastair Young, is expecting a mixture of outcomes: some deals will be halted but others will be accelerated, depending on each set of circumstances. He told NGW: “The combination of the ‘black-swan’ event of the coronavirus pandemic and the collapse in the oil price will put the brakes on some deals in the UKCS. Low and volatile oil prices and other uncertainties can widen bid/ask spreads between buyers and seller making it hard to close deals.” However, experience shows that even here, imaginative solutions can be made to work: one approach that he suggested would make a come-back was the post-completion contingent payment kicker that is linked to a future oil price recovery. “This is a way to bridge the price expectation gap between buyers and sellers,” he said. But there could also be some distressed takeovers in the UKCS as hedges roll off and the low oil price starts to bite less well-capitalised oil companies. “There are deals to be done in the UKCS and buyers with access to capital who are willing to look through the current downturn could emerge as winners,” he said. One deal that no longer looks quite as good as before, on the present terms, is Premier Oil’s proposed $870mn purchase of upstream assets from BP and Dana Petroleum. The cash would come from a $500mn equity raise, a $300mn loan and its own cash. Even before the present crash, one major creditor, the hedge fund Asia Research and Capital Management, had resisted the deal, saying it would over-burden Premier with debt. Premier put the matter before a judge to decide if the fund could block it. The fund had been a lone voice against the deal; but a positive legal judgement would not mean that the deal will proceed, an industry source close to the deal told NGW. While the judge made up her mind, the buyer could also reconsider the merits of the deal, he said. |

Interview with Oil & Gas UK: ‘This time it’s different’

The oil and gas industry had been making a cautious come-back since the last crash in 2014-5, but now the atmosphere is distinctly chillier. With the low-hanging fruit long gone, the upstream has fewer options for survival as the benchmark Brent crude price plunges below $25/b.

Oil & Gas UK (OGUK), representing contractors and producers, told NGW late March that this crash is different. Market intelligence manager Ross Dornan said the decline in prices this time was “almost immediate. There are also questions about the price Saudi Aramco is selling at, and how long Russia and Saudi Arabia can sustain prices of $30 or $40/b. Is today’s price the result of competition between producers, or is it dumping?” Dornan asked.

OGUK’s Efficiency Task force was set up after the last crisis in 2015 and Dornan told NGW: “It has made really good progress. Costs have come down a third, of which a third is from cost deflation; but the rest is sustainable.

“This is a really challenging period, and for some companies it is a question of survival for the E&P companies and their suppliers. There will be more insolvencies, more consolidation. Companies will no longer be able to protect their dividend and will keep cash. But the oil and gas will still be there, even if another company ends up producing it.”

The government has been helpful to the sector: including the offshore on the list of key workers who have to be able to move around the UK to do their essential work as restrictions increased was a “very important step, as our industry is vital to the country’s economy,” Dornan said. “What is going on in the global economy underlines the importance of our own domestic production.”

A lot of work is being done to understand who is eligible to benefit from the government’s resilience package of £350bn. Companies can access essentially interest-free loans worth up to £5mn if their turnover is under £45mn/yr.

There is also the Covid Corporate Finance Facility for companies that can demonstrate that they make a material contribution to the national economy. Those funds are disbursed on a case by case basis. And there is the guarantee that the government will pay anyone who is laid off the lower of 80% of salary or £2,500/month, he said.

“These schemes only opened March 23 and we are working with our members to see if there are any gaps in the financing. Most oil and gas companies are large but a lot of our members have turnover under £1mn and some upstream companies have not yet achieved cashflow. Those that do have cashflow will see less of it in the low-price regime and they also face the risk of disruption to their operations. This is a perfect storm for contractors: deferred operations at a time when companies are already in a very difficult position.”

Equally serious is the need to retain the people with the skills and resources as a means of ensuring security of supply and enabling the transition to a net zero carbon economy, as set out in Roadmap 2035, which was developed by OGUK with input from over 5,000 people across the industry. “A lot of companies will be crucial to our ambitions if we are to do the transition in a cost-efficient way,” he said.

There has not been any change in the statute of the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA), the upstream regulator: its objective is still to enable the delivery of the maximum economic recovery (MER) of the UKCS, he said. He said that MER was “compatible with the energy transition and the lower carbon footprint. But it will need behavioural change and some will require capital to do that: electrification needs money.”

And he said the OGA has taken a “pragmatic approach to the crisis.” For example, he cited the letter from its CEO Andy Samuel which mentions the possibility of licence commitments for the 32nd round, which bidders made in a very different market environment from today’s. “The OGA’s approach has always been to encourage co-operation and to regulate as a last resort,” he said.

Samuel, in his letter, said: “In the midst of the serious threats facing the sector, we have not lost sight of the importance of achieving the UK’s net zero ambitions. We are continuing our programme to integrate net zero considerations into our work because we know that the oil and gas industry can play a significant and leading role in helping the UK achieve this. However, sensitive to the other immediate priorities facing the industry, we will implement this important net zero programme in a way which is both considerate and flexible.”

|

UK in figures UK gas demand fell by 2bn m³ year on year in 2019 – a decrease of 3.9% – and is now 22% lower than ten years ago. This trend is the result of various factors, primarily improved energy efficiency and changing energy use patterns, according to the OGUK’s Business Outlook 2020, published early March.

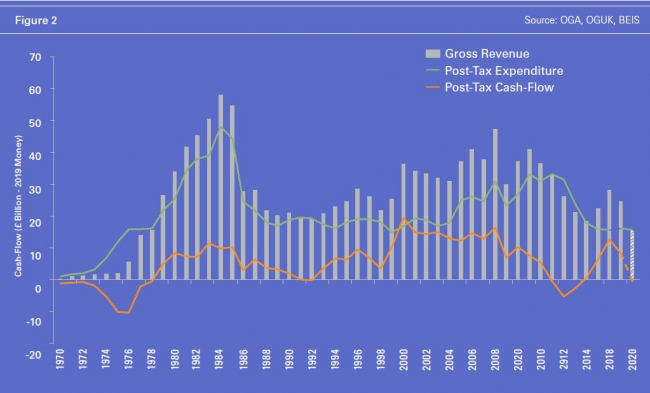

Renewable output grew by 13% in 2019 and is now more than four times greater than in 2010. The UK benefits from a strong and increasingly diversified gas supply, including volumes flowing from domestic production, interconnectors with continental Europe and increasing LNG shipments from around the world. The increasingly physical linkages and exposure to other international gas price markers are applying significant downward pressure. In the short term, given ample volumes of continental gas and LNG imports, it is likely that the UK market will continue to be oversupplied, which will act to keep prices relatively low. Some offshore jobs have already been cut as operators rein in spending, and OGUK is contemplating a return to the dismal drilling figures of 2015. The supply chain has already done what it can to keep operating unit costs down, following the last crash in 2014. So it is now "paper-thin," says OGUK CEO Deirdre Michie. The report says that the investments of almost £5.5bn ($6.2bn) in the last three years would struggle to reach £4.5bn this year. OGUK had expected the number of wells drilled to be in a similar range as in 2019; however based on recent experience, it is conceivable that this could be down more than a third, repeating the cuts seen in 2015-16 when activity slumped to a record low. This drilling reduction will also impact future production and revenue growth in the short term as projects are allowed to stagnate. The UK produced almost 1.7mn barrels of oil equivalent/day last year, a fifth more than in 2014. This was 51% of gas demand and 74% of demand for oil products. But OGUK estimates that UKCS production revenue, which exceeded £28bn in 2018, could be half that this year for the same output. The UKCS could operate at a loss this year; for revenues to equal expenditures – cash-flow neutral – oil would have to cost at least $40/barrel and gas 25 p/therm (Figure 2). But that is unlikely. Large companies could possibly hedge their exposure to oil and gas by moving into other energy sectors but the smaller ones will need to find innovative solutions if they are to survive. “Partnerships and meaningful collaboration will be required to help as many as possible to weather the storm,” said OGUK. |

.JPG)

Following a significant increase in gas demand for electricity generation in 2016 to offset declines in the use of coal, last year electricity generated from gas decreased by 2% and is a tenth lower than 2016.

Following a significant increase in gas demand for electricity generation in 2016 to offset declines in the use of coal, last year electricity generated from gas decreased by 2% and is a tenth lower than 2016.