Ukraine at the Crossroads

There is great potential still in the country’s gas sector, but Kiev must be bold if it wants to attract the investment – and players – it so desperately needs, argues Philip Vorobyov*

IN AUGUST 2014, Ukraine’s government more than dou- bled its taxes on gas production for private companies as part of a broader effort to shore up its embattled budget.

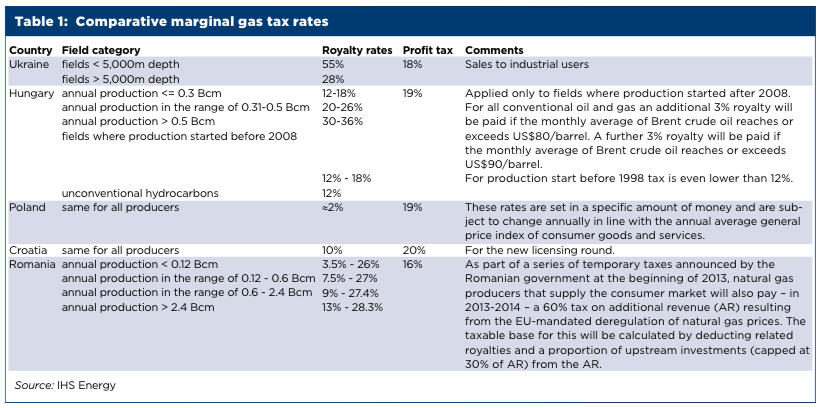

The result is a combined marginal tax rate of close to 70%, putting Ukraine on a par with hydrocarbon exporting countries such as Norway, Russia and Kazakhstan.

But Ukraine is not an exporter of hydrocarbons. Not any more. It is a country in the midst of a desperate gas shortage, as it continues to negotiate with Russia over gas supplies needed to cover demand for the winter.

The tax increase, originally introduced as a temporary measure running until the end of the year, could now be extended indefinitely. This move, while understandable in the current political circumstances, could cripple – if not kill – private gas production, which has started to increase rapidly during the past year.

This would be a costly mistake, because small, private gas companies – still living on the margins of the industry – could prove to be one of the pillars of the energy inde- pendence Ukraine so desperately wants.

After all, it was small exploration and production (E&P) companies, not the majors, which launched and sustain the E&P revolution that will soon turn North America from the world’s biggest importer to an exporter of hydrocar- bons. To make something similar possible in Ukraine, great change – and thus great humility – will be required from a country that used to be a natural gas power.

Looking back

Ukraine was once the cradle of the Soviet gas industry. The development of Ukraine’s major gasfields – notably the Shebelinka field in 1950s – resulted in a production boom that saw Ukraine’s gas output briefly rise to almost 70 billion cubic metres a year (cm/y). In fact, the first big gas pipelines built in the Soviet Union were designed to carry gas west to east, rather than east to west, as they do today. Ukraine’s economy was built on cheap, plentiful gas and its gas professionals became the backbone of the Soviet gas industry.

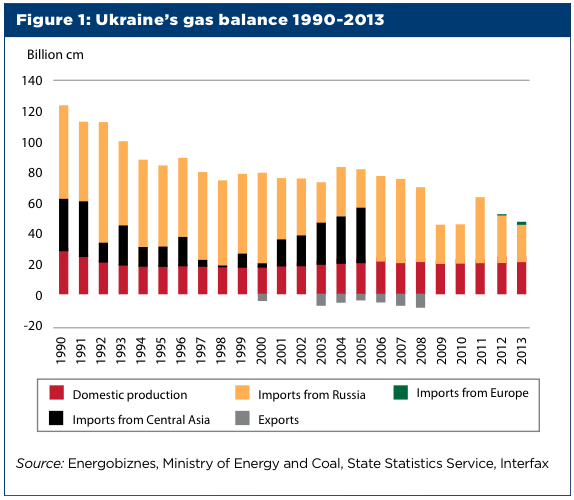

However, the natural depletion of Ukraine’s largest fields, coupled with major discoveries in Turkmenistan and West Siberia, saw Soviet planners shift their focus and Ukraine’s output stagnate. But Ukraine’s economy and population continued to depend heavily on natural gas, which by the late 1980s was mostly drawn from the Siberian and Central Asian supergiant fields, turning Ukraine into a gas bridge from Eurasia to Europe. As a result, Ukraine entered the post-Soviet period as a major importer and transit artery for gas from Russia.

Although Ukraine’s gas consumption has declined by more than 50% since it gained independence in 1991, it still consumed 50 billion cubic metres (cm) in 2013, making it Europe’s fourth largest consumer after the UK, Germany and Italy. It also continues to rely heavily on gas flows from the east (see Figure 1).

Despite wholesale changes to its economy since independence in 1991, the state continued to play a dominant role in Ukraine’s gas sector, both directly and through extensive regulatory oversight. While most other industry was privatised, Ukraine’s hydrocarbon production has remained mostly in state hands. Ukraine’s gas industry is dominated by state-owned Naftogaz Ukrainy. Its main producing subsidiary, Ukrgazvydobuvannya accounted for 15 billion cm of the 21 billion cm Ukraine produced in 2013. A further 3.6 billion cm of gas was produced by Chernomorneftegaz, a 100% Naftogaz production subsidiary responsible for production in the south of the country (mostly offshore Crimea) and Ukrnafta – an oil company in which Naftogaz holds 51%. The remaining 2.35 billion cm was produced by independent companies. Thus, in total, state-controlled companies accounted for 89% of gas production in Ukraine in 2013. By contrast, Gazprom controls 70-75% of gas production in Russia.

Since 1991, Naftogaz’s central role has been two- fold: to operate Soviet legacy gas fields, delivering this “cheap inheritance” to Ukraine’s population at low prices; and to manage Russian imports to cover the rest of the economy’s gas needs.

The government sets gas prices for the residential and utility sectors at what it believes to be the cost of producing and transporting the fuel (although in reality they tend to be far below real costs). Ukraine’s industrial needs are met mainly through imports, but also from private gas production.

The government sets a maximum limit on industrial prices based on the price of imported gas at the border plus transportation costs. Privately produced gas is delivered at negotiated prices that are kept below the maximum established price level.

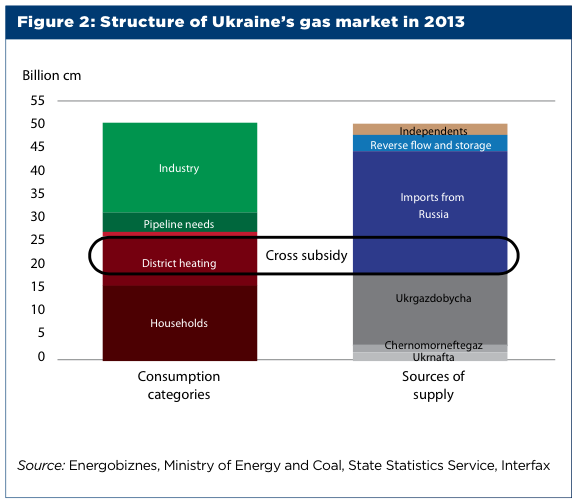

There is a complication – domestic residential and utility demand is not met by domestic production (see Figure 2). While Naftogaz produces just enough gas to cover direct residential consumption (17 billion cm in 2013), gas for heating (10 billion cm in 2013) is imported at prices, which are generally higher than the regulated price. The cost of this subsidy is supposed to be covered by fees from transiting Russian gas to Europe.

Conditions

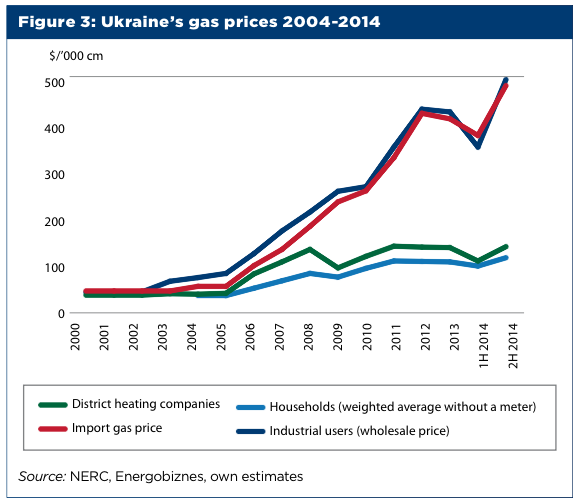

This complex system worked as long as two conditions were met: that plentiful and relatively cheap Russian gas was available; and that the existing portfolio of Naftogaz’s producing assets required minimal investment. But the status quo’s commercial underpinnings are breaking down. The surge in prices for imported Russian gas during the last decade has put increasing pressure on the Ukrainian budget and Naftogaz’s bottom line. While import prices increased, the Ukrainian government has been reluctant to raise gas prices for the population. As a result, the burden of the cross-subsidy has also increased (see Figure 2).

Meanwhile, revenues from gas transit fees – meant to plug the financial gap – have not increased proportionally as the volume of Russian gas transiting Ukraine has been gradually falling (from 128 billion cm in 2006 to 86 billion cm in 2013). This is due to the commissioning of the Nord Stream pipeline, which carries Russian gas directly to Germany, and an increase in gas transit through the Yamal-Europe pipeline via Belarus and Poland. On top of that, non-payments, especially from the heating sector, have also increased. At the end of 2013, Naftogaz’s financial losses, including non-payments, stood at roughly $4 billion.

As a result, Naftogaz has been experiencing difficul- ties funding even the minimal needs of its upstream assets, resulting in stagnating production. Since 2011 its capital investment and drilling has dropped 30%. This, coupled with the loss of control over Crimea-based Chernomorneftegaz earlier this year, will likely result in continued production declines for Naftogaz as a whole for the next few years.

While the Ukrainian government has made commit- ments to the European Union and the IMF to gradually unwind cross-subsidies by raising domestic gas prices, restructuring Naftogaz and eventually privatising its upstream assets, this process will likely take many years due to its highly politically and socially sensitive nature. Naftogaz is thus unlikely to channel large-scale invest- ments into gas production any time soon.

But a potential alternative source of investment and gas production growth is starting to emerge: private gas producers.

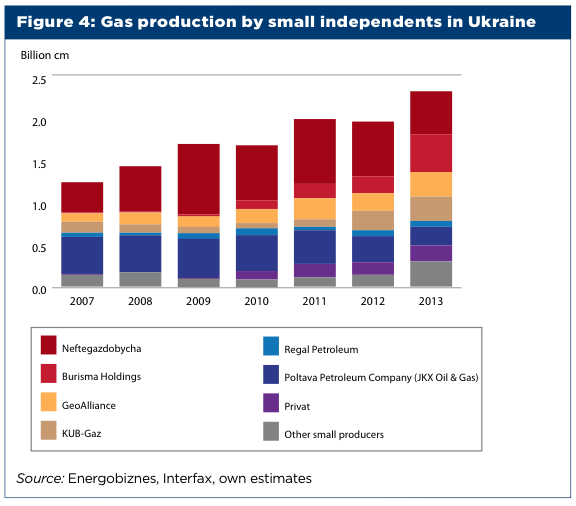

Ukraine’s independent E&P sector emerged shortly after independence. For a variety of reasons, including low gas prices, non-payments for gas and extremely chal- lenging operating environment, few dared to invest in gas production during the first post-Soviet decade. But rising prices for imported gas since 2004 and the ability to sell gas at high prices to industry have started to attract inves- tors – mostly Ukrainian, some foreign – into the sector. Since 2007, independent gas production in Ukraine has almost doubled (see Figure 4).

In first half of 2014, independent production growth grew markedly – even as war broke out in Eastern Ukraine – increasing by over 30% compared to the same period in 2013.

Today there are 22 registered gas producers in Ukraine, while more than 50 entities hold exploration and production licences. The combined gas reserves held in private hands now totals almost 100 billion cm. A large chunk of both production and reserves lie in the Dnepr-Donetsk basin and is controlled by seven groups of companies: Neftegazdobycha, KUB-Gaz, Burisma, GeoAlliance, Privat, Regal Petroleum and JKX Oil & Gas. Of the seven, London-listed JKX Oil & Gas and its Ukrainian subsidiary Poltava Petroleum Company (PPC) have the longest track record.

PPC began operations in 1994 at the Novonikolayevskiy cluster of licences, also known as Novonik, in the Poltava region – the heart of Ukraine’s hydrocarbon production. Since then the company has invested close to $500 million in its operations. PPC is involved in developing a broad range of assets and businesses that could be replicated by new entrants in the future. This includes “sweating” legacy assets, such as the Ignatovsoye, NovoNikolayevskoye and Molchanovskoye licences in the Novonik cluster, through infill drilling and well workovers. A waterflood of the Molchanovskoye oilfield is also in the advanced plan- ning stage. The Elizavetovskoye field has recently been brought on stream via two wells, while a third has been drilled to test deeper reservoirs. On top of this, PPC has been exploring the Zaplavskoye licence. In August 2013 the company completed Ukraine’s first and one of Europe’s largest multi-stage well fracture of horizontal well R103 at the Rudenkovskoye field – the first serious attempt to develop Ukraine’s tight gas potential.

But what has been done so far by independents could just be the tip of the iceberg. Ukraine could still hold a wealth of opportunities for E&P investors with an appetite for risk.

End of the line

After more than a century of gas production, Ukraine’s main hydrocarbon-bearing regions – the Carpathian basin in the west and the Dnepr-Donetsk basin in the east – are very mature. The remaining easy-to-produce gas from large and relatively shallow fields operated by Naftogaz is running out. The future appears to lie in the country’s vast unconventional hydrocarbon resource, mostly in tight gas accumulations in the east and shale gas in the west. These hold estimated poten- tial resources of between 7 trillion and 16 trillion cm. Ukraine’s Energy Strategy to 2030 predicts a gradual decline of production from conventional fields, with all new growth coming from unconventional sources.

.png)

As part of this strategy, the Ukrainian government introduced a number of important changes to legislation and last year signed its first two production sharing agreements (PSAs) to develop unconventional gas with Shell and Chevron. The new PSAs are an important mile- stone for Ukraine’s gas industry. However, the lead times on these projects are almost certain to be long, given the lack of understanding of the geology and economics of unconventional gas in Ukraine.

The fact that no country outside of North America has yet successfully commercialised its unconventional resources is also problematic. The recent exit of several international companies from neighbouring Poland due to a combination of poor early well results and high costs is a reminder that Ukraine’s unconventional future is far from secure.

Meanwhile, despite its long history as a gas producer, Ukraine still appears to have significant conventional potential, which, under the right circumstances, could be tapped relatively quickly.

Additional investment

Ukraine’s official gas reserves stand at around 1 trillion cm. Given today’s production rates of 20 billion cm/y, this gives Ukraine a reserves-to-production (R/P) ratio of more than 50 years. By comparison, according to the Energy Delta Institute, the R/P ratio for the European Union aver- ages 14 years. This suggests that there is a great deal of scope for accelerating production through additional investment across a number of areas.

Firstly, firms could look at existing producing fields.

Efficiency was not one of the strengths of Soviet-era development. Many fields in production in Ukraine have ample opportunities for enhanced recovery through well workovers, appraisal of bypassed zones, recompression, hydraulic fracturing and other techniques. Recently, Ukrgazvydobuvannya – Naftogaz’s main production subsidiary – stated that of its 674 billion cm of booked reserves, 384 billion cm is not fully in production and requires additional investment in modern production techniques.

Small fields too offer scope to increase production. Approximately a third of Ukraine’s gas reserves today are found in small fields, with reserves of under 5 billion cm each. Of Ukraine’s 380 or so discovered gas fields 100 – all of them small – are not in production.

Finally, an increasing share of Ukraine’s reserves are locked in fields that have tight or extremely variable res- ervoirs at greater depth (5,000-6,500 metres) and much higher pressure. Their appraisal and development is much costlier and requires top-notch technical expertise.

Despite its maturity, Ukraine retains large conventional exploration potential (25 billion barrels of resources, not including the southern region). But again, most of these undiscovered reserves will be found at greater depth and in increasingly smaller concentrations in more complex geological conditions.

Even after 100 years as a hydrocarbon producer, Ukraine retains enormous conventional gas potential. But this will also be much costlier to realise, with more heterogeneous reserves requiring focus and tailor-made solutions. To realise this potential, Ukraine will have to nurture the independent E&P sector. The most critical indicator for E&P investors is the upstream tax regime where both tax rates and predictability play equally important roles.

As part of an effort to reduce its fiscal deficit, the Ukrainian government introduced a sharp increase in gas taxation for private producers in August 2014. This entails raising gas royalty – known as a subsoil fee – from 28% to 55% of gross revenue for gas produced from reservoirs shallower than 5,000 metres, and from 14% to 28% for gas produced at a depth of more than 5,000 metres.

Tax rises

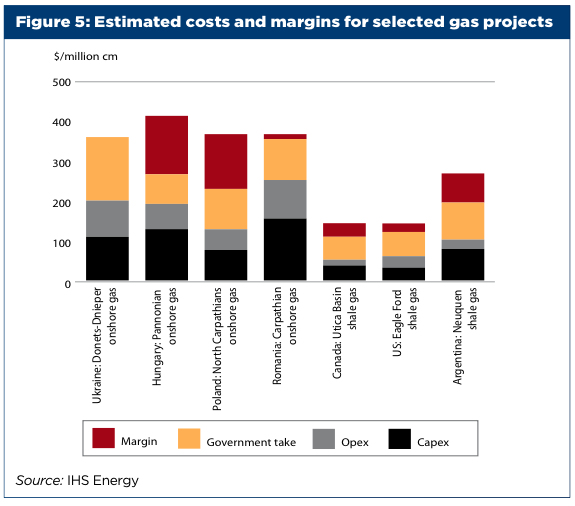

This was the second tax increase announced in 2014, and the fifth in the past four years. As a result, Ukraine now has one of the heaviest tax regimes in Europe. Its combined marginal tax rate (around 70%) is now much closer to those imposed by major hydrocarbon exporters such as Norway, Russia and Kazakhstan rather than its peers in Eastern Europe, such as Poland, Romania and Hungary (see Table 1).

The Ukrainian finance ministry justified the tax increases, saying private gas producers were enjoying super-normal profits thanks to high gas prices on the one hand and low production costs on the other. Ministry officials revealed that they based their calculation on one key assumption: the costs of independent producers are close to those of Naftogaz and its production subsidiaries, for which the government sets upstream transfer prices at $20-30 per 1,000 cm. But there are flaws in this reasoning.

First of all, Naftogaz’s portfolio consists of Ukraine’s largest and best-quality fields. Even so, officials from Naftogaz’s main production subsidiaries have repeat- edly stated that prices set by government regulators do not fully meet their operating costs, let alone capital investment for exploring and developing new fields. Most recently, an advisor to the president of Naftogaz stated that full-cycle costs of production for the company are close to $200/’000 cm. A recent report by interna- tional consultancy IHS reveals that after the recent tax increases, exploration for and development of new fields in Ukraine has become economically unattractive both in absolute and relative terms (see Figure 5).

Secondly, independent producers are involved in developing a variety of assets, all with very different risk profiles and costs. A tax regime with a heavy royalty component will increase the tax take in the short term, but could sink projects involving high geological and technical risk.

International experience has shown that regions with mature resource bases in the latter stage of development require flexible tax regimes. Such tax frameworks can accommodate a variety of investment needs and risk profiles for projects ranging from reviving depleted fields to wildcat exploration of previously bypassed prospects. The switch away from a royalty-based to a profit-based tax regime in the UK North Sea in the 1980s, a move followed by Norway in the 1990s, saw a revival in that mature petroleum province.

An alternative to profit taxation could be a more flexible royalty regime, with different rates set depending on the degree of project difficulty. Such a system has recently been implemented in Russia for both oil and gas projects.

At present, Ukraine’s royalty regime only allows for differentiation depending on whether producing horizons are shallower or deeper than 5,000 metres. This is not flexible enough.

For example, many independent projects target fields that are in the 4,000-5,000 metre range. While the differ- ence in capital outlays with projects below 5,000 metres can be negligible, the tax rate would be significantly higher. Finally, other variables such as reservoir quality, degree of depletion and size of deposit can seriously affect costs and will need to be taken into account. While the new tax legislation allows for a two-year tax break on new wells, it is unlikely to make a serious enough impact on the economics of most projects, especially those with an exploration component.

A great deal more thought needs to go into upstream tax legislation in Ukraine. And once such legislation is passed, it would be important for the fiscal regime to remain in place and largely unchanged for a reasonably long period of time. After all, the boom in unconventional production in the US was preceded by a 20-year period during which significant tax breaks were granted for these types of projects.

But a stable and flexible tax regime is only part of the puzzle. For E&P activity to pick up, Ukraine will need to gradually address a range of other issues affecting the investment climate in its energy industry and beyond.

Limited entry

Despite the recent surge in independent production, the Ukrainian E&P sector is a high-cost environment with significant entry barriers for new players. One reason is that the services sector remains under-developed and highly concentrated – a mirror image of its clients on the production side. There is little competition in areas such as seismic acquisition, drilling and infrastructure construction. Advanced production technology, especially for hydraulic fracturing, is scarce and very expensive to mobilise. Technical specialists with knowledge and practical experi- ence in advanced exploration and production techniques are also in short supply and command very high salaries.

The best way to remedy this is to increase the number of producers and thus the size of the services market.

But for this to happen, Ukraine will need to introduce significant amendments to sector regulation, currently focused on resource management and control rather than stimulation of investment. This means simplifying and streamlining licensing and approval processes, which are heavily bureaucratised and often opaque, especially at regional level. A review of often anachro- nistic technical rules, which still prohibit such common practices as underbalanced drilling and multiple zone completions, will be required to give producers more field development options. Serious thought needs to go into stimulating exploration through tax incentives, more realistic licence valuation, as well as through easier access to existing seismic and well data.

The need to stimulate private gas production is, in principle, well understood in Ukraine. Ukraine’s Energy Strategy to 2030 explicitly acknowledges the importance of private investment in upstream activities.

A list of measures to improve Ukraine’s E&P investment environment was drawn up with the help of international consultants such as IHS and McKinsey in 2012. While some of these measures have been implemented, much still remains to be done.•

Philip Vorobyov is a commercial executive at JKX Oil & Gas. This article was first published by the Petroleum Economist.