UN climate change and energy security [NGW Magazine]

Following a joint session at Incheon in South Korea, the UN Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued October 6 a Special Report on the ‘impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways.’

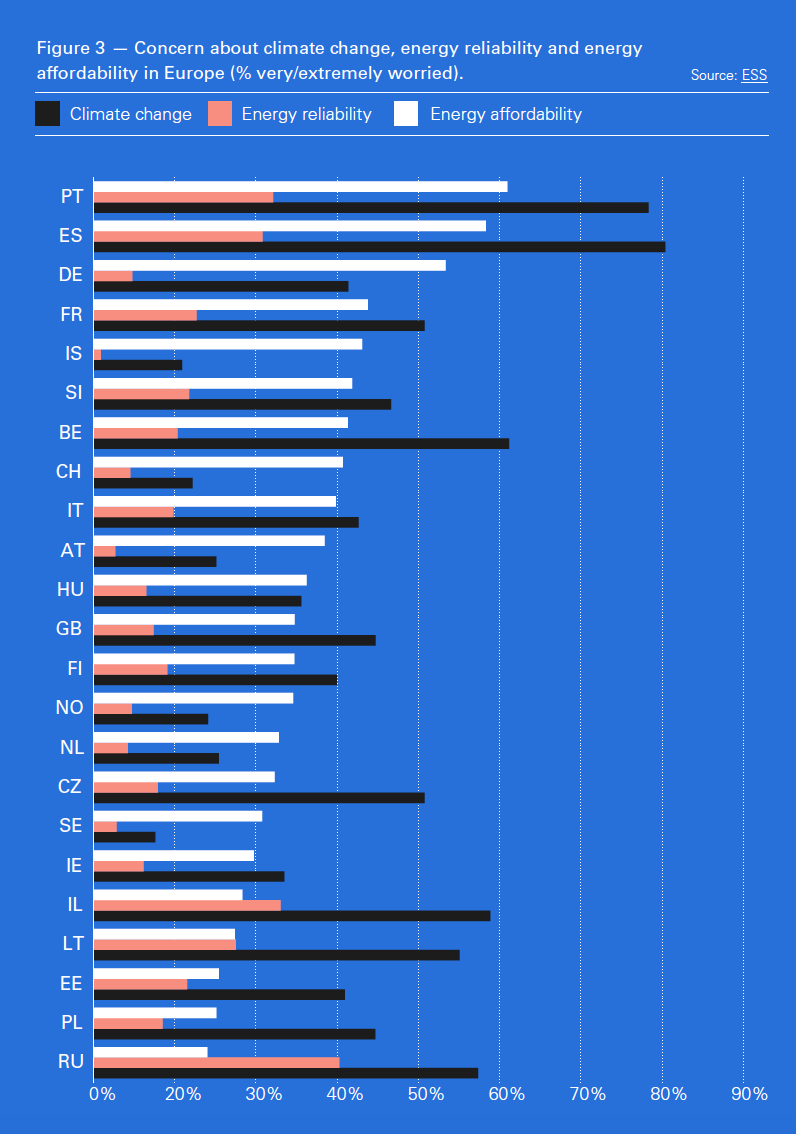

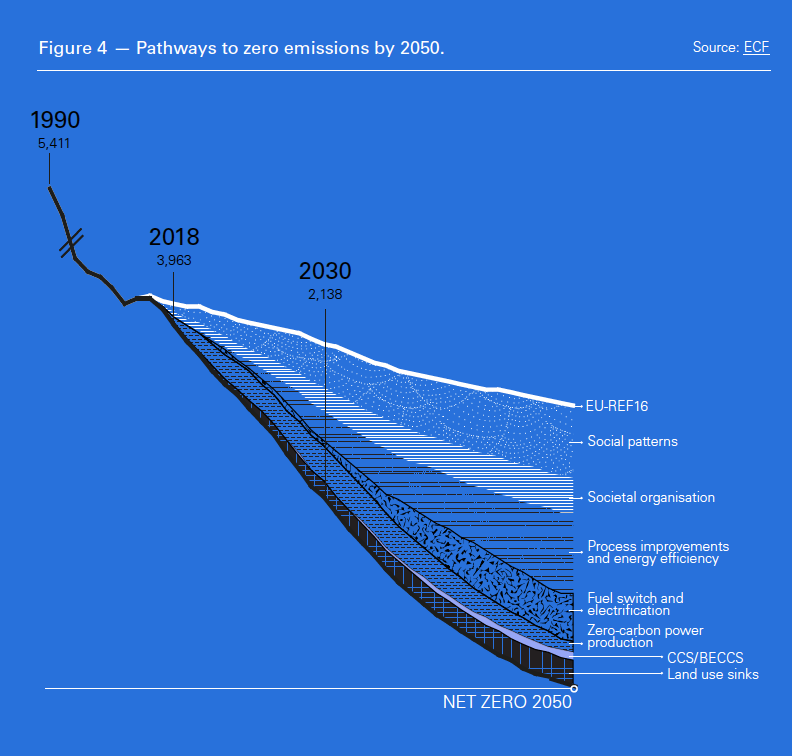

The report, commissioned by the Paris agreement signatories, makes grim reading. It states that global warming has already exceeded 1 °C (Figure 1) and is on track to reach a temperature increase of 3 °C by 2100 (Figure 2) – well in excess of the Paris agreement to limit the increase to 1.5 °C – with “far reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.” This report is intended to provide the key scientific input for the Katowice Climate Change Conference in Poland in December, when governments review the Paris Agreement to tackle climate change. It will certainly bring more urgency to its deliberations.

Presenting the report, Panmao Zhai, co-chair of IPCC Working Group I, said: “One of the key messages that comes out very strongly from this report is that we are already seeing the consequences of 1 °C of global warming through more extreme weather, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice, among other changes.” The original target to limit the rise of temperature to well below 2 °C by 2100 is no longer acceptable, even though many thought even that was impossible. The “risk of long-lasting or irreversible changes” is rising fast.

The report highlights the serious climate change impacts of such an eventuality and makes recommendations for the necessary far-reaching measures to be quickly implemented “in land, energy, industry, buildings, transport and cities.” Key among these is that “Global net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) would need to fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050. This means that any remaining emissions would need to be balanced by removing CO2 from the air.”

The co-chair of IPCC Working Group II Debra Roberts said: “This report gives policymakers and practitioners the information they need to make decisions that tackle climate change while considering local context and people’s needs. The next few years are probably the most important in our history.”

The report received immediate and widespread coverage worldwide. Achieving the report’s key recommendations would require extending decarbonisation progress in the electricity sector into other areas such as heat, transportation, industry and land management. It would also require removing billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through methods such as reforestation, soil carbon sequestration or direct air carbon capture and to do this at a rapid pace.

The report also outlines a plan, based on a ‘manual of solutions’, of how to achieve its recommendations. The world must invest $2.4tn in clean energy every year from now to 2035 and reduce coal-fired power generation to more or less zero by 2050.

The report piles pressure on policy-makers, business and industry to take the required measures to achieve this change. This would require worldwide coordinated and concerted action, involving all major economies, at a scale never seen before. But how practical is this and how can it be achieved?

Level of response

Apart from strong response by environmentalists and a short-lived response by the media, general response to the IPCC report has been muted. In fact the best way to describe this is that the IPCC findings have been greeted by global climate change indifference. So why?

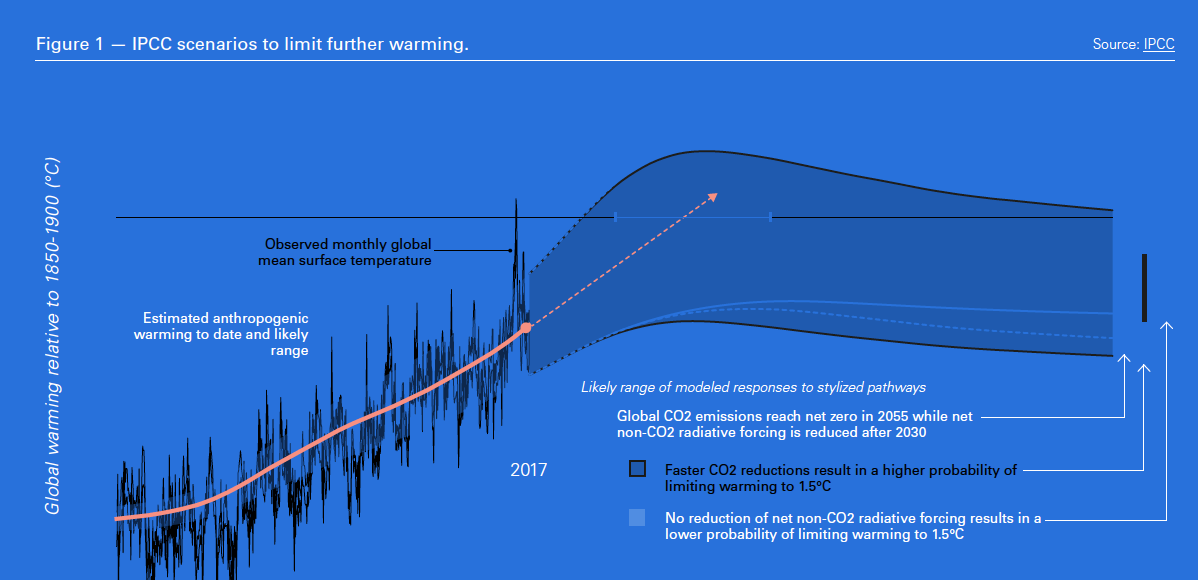

Perhaps a European Social Survey (ESS) report released in September can shed some light. This was based on a public survey involving 44,387 people in 23 European countries.

According to the report, a great majority of Europeans think that climate change is happening, but do not have strong concern about the issue. Worryingly, only just over a quarter of the respondents were “very or extremely worried about climate change.” But affordability was a major consideration for most (Figure 3).

In fact, the results show that “while most Europeans think the consequences of climate change will be bad, many only feel a moderate responsibility to reduce climate change and think that personal efforts will not be very effective.”

However, there is high support for renewable energy sources –including electricity generation from renewables – and energy efficiency regulations across the whole of Europe. There is also support for environmental policies to reduce climate change. But Europeans “do not think that it is highly likely that limiting their energy use would help to reduce climate change.”

Interestingly, even though there is support for renewable energy subsidies, only 30% of respondents wanted higher fossil fuel taxes, compared with 40% against.

If these are the views of Europeans who are generally well-informed about climate change, it would perhaps explain the general indifference with which the IPCC report has been received internationally.

Two separate public surveys carried out in China in 2017 and 2018 show that Chinese people are aware of climate change. About 94% believe climate change is happening; 66% believe that it is mostly caused by human activities; 83% know about the low-carbon transition; 77% are satisfied with the low-carbon performance of their city; and about 74% are willing to pay extra for climate-friendly products.

In addition, 97% support the Chinese government’s actions to limit greenhouse gas emissions and 94% support remaining in the Paris Agreement. Not surprisingly, air pollution dominates public concern of climate risks. But even though they are willing to spend money to offset carbon emissions, they are only prepared to make small lifestyle changes.

Evidently, similarly to Europeans, the Chinese public is well informed about climate change, but the small lifestyle changes they are prepared to make will not bring about the unprecedented change IPCC believes is needed.

Policy response

Following the release of the report, IPCC chairman Hoesung Lee said: “We assess the scientific information and then provide policy-relevant messages to our member governments as well as the relevant stakeholders.” He added: “We provide a manual of solutions. It’s up to them to use this manual, considering the constraints or opportunities existing in different countries. It’s their decision, but we provide the scientific information.”

UN secretary-general, Antonio Guterres backed the report, saying it was “an ear-splitting wake-up call to the world. It confirms that climate change is running faster than we are, and we are running out of time." He urged that there is a “need to end deforestation and plant billions of trees; drastically reduce the use of fossil fuels and phase out coal by 2050; ramp up installation of wind and solar power; invest in climate-friendly sustainable agriculture; and consider new technologies such as carbon capture and storage.”

But are governments rushing to use the ‘policy-relevant messages’ and the ‘manual of solutions’ the IPCC has provided?

Global policy efforts to address climate change face a degree of uncertainty owing to the lack of leadership, particularly from the US. Even the EU and China, despite strong commitment to the Paris Agreement reaffirmed in July, face challenges.

The European Commission is a strong advocate, pushing policy within the EU, but as public opinion shows it will struggle to get the support needed to push through radical policy changes.

Two EU commissioners, Miguel Arias Cañete, climate commissioner, and Carlos Moedas, research and innovation commissioner, commented on the IPCC report, the latter stating: “We need to start preparing to achieve a carbon-neutral economy as soon as possible this century. This is the message we will take to Katowice,” saying in a written statement: “In short, as there is no planet B, saving our planet Earth should be our number one mission.”

They also stated that new agreed targets for energy efficiency, 32.5%, and renewable energy, 32%, “will lead to steeper emission reductions for the whole EU – some 45% by 2030 instead of 40%,” matching the IPCC recommended reduction in emissions. However, after facing resistance and losing the support of Germany, the EC was forced to drop its recommendation to raise emissions reduction from 40% to 45% relative to 1990.

The position of Chinese experts is that the country’s climate change targets and commitments are in line with the country’s stage of development and circumstances, and they will not change just because of new discussions regarding the 1.5 °C target. China is expected to remain committed to working towards its own low-carbon development goals.

India’s environment minister, Harsh Verdhan, said that the country had not waited for a report to tell it that climate change posed a threat. India is making all efforts to combat global warming. Separately, AK Mehta, additional secretary ministry of environment, said: “India recognises climate change to be a real threat and we will do whatever we can in our own capacity. Denying the reality of climate change is not going to help anyone. We will act like a responsible nation.” But even though in October India increased its target of non-fossil fuel in its power mix to 40% by 2030, a lot more needs to be done to meet IPCC recommendations.

The US administration has been mostly quiet. Even though the president, Donald Trump, has admitted that climate change is not a hoax, he has not hidden his mistrust of the report. In the US, lack of national leadership is leaving states, cities and business to take whatever action they can. This might be commendable under the circumstances, but it is no substitute for federal government support.

The world governments, business and industry must be ready to spend $2.4 trillion in clean energy annually. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates, this is about seven times the amount invested globally in renewables in 2017.

It is also equivalent to about 3% of global GDP. As an example, for the UK this would amount to over 1.5 times the defence budget being spent annually on clean energy. Neither the UK nor any other major governments have rushed to make such commitments following the IPCC report.

IPCC probably expected this. Referring to transition options, the report admits that “these options are technically proven at various scales, but their large-scale deployment may be limited by economic, financial, human capacity and institutional constraints.’’

Without making such commitments it will not be possible to achieve what IPCC recommends. If past responses to earlier climate change reports are an indication, little serious action can be expected. Responses by major economies so far do not give confidence that it will be any different now.

The key to all of this may not lie in the developed world but in Asia, with China and India at the forefront as the lead energy consumers in the world. It is highly unlikely that these countries will sacrifice economic growth and energy security by fully divesting from coal even by 2050. The hope lies in the faster growth of renewables, something which the IPCC report may help accelerate.

The world needs to decarbonise and all countries must do it collectively. But it remains to be seen what emerges from the review by world governments of the Paris Agreement at the Katowice Climate Change Conference in Poland in December. Not only bolder commitments will be needed, but they must also be adhered to. This highlights the enormity of the problem.

Impact on oil and gas

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), carbon emissions are likely to increase in 2018 for the second year running. Executive director Fatih Birol said that this is due to the growing global economy driving energy consumption and particularly coal, oil and gas use. He added that: “Energy efficiency improvements and renewables are not good enough to reverse that.” This makes attaining Paris temperature targets that much more difficult.

All mitigation scenarios considered in the IPCC report to limit temperature rises to 1.5 °C, about 90 in total, require steep reductions in the consumption of fossil fuels and rapid growth in renewable energy.

According to IPCC, the median requirement is for fossil fuels to drop from 84% of global primary energy in 2020 to 36% by 2050, the share of renewables must increase from 15% to 61% and nuclear power must double. Even then there will be a need to remove vast quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

In terms of power generation, renewables should supply 70% to 85% by 2050, with coal reduced to 2%. Natural gas could maintain an 8% share provided it is combined with CCS so that total global net emissions vanish by 2050.

Based on the above, the report highlights the risk to further investments in natural gas-fired power plants and suggests that more of them should be replaced by renewables.

The scale of these changes, and the pace at which they are required to happen, are unprecedented. They would cause massive upheaval not only in the way energy is produced and consumed, but also in all aspects of society.

But there are practical questions. How possible is it to achieve such massive changes, while keeping the lights on, and how affordable would this be. Affordability was a key concern of the Europeans that participated in the survey reported.

Gas, as the cleaner of all fossil fuels, has a role to play, for at least a few decades. This role may be reduced in time in power generation, but it is important in all other energy sectors. This is the reason why the oil and gas companies are investing in natural gas – and ways to tackle emissions from gas, including methane – as the fuel of the future.

The IPCC report also sets out a possible role for gas during transition. “Using natural gas – including shale gas produced with low-emissions practice – in a modern gas-fired plant would reduce emissions per kWh by half when shifting from the current world-average coal-fired power plant, evaluated using 100-year global warming potentials. Unconventional gas could therefore lower emissions for the transitional period where gas competes with coal, if gas losses and additional energy requirements for the fracturing process can be kept relatively small.”

Until renewables deliver the results expected of them, and reliably so, oil and gas companies are pushing for policy-makers to recognise gas as a longer-term part of the solution to climate change, as a ‘destination fuel’ rather than just viewing it as a ‘transition fuel’.

Industry response

This message from the oil and gas industry came loud and clear during the Oil & Money conference in London October 9-11. Coming soon after the release of the IPCC climate change report, it provided an opportunity for the oil and gas industry to give its response.

The CEO of Anglo-Dutch major Shell Ben van Beurden said that it will be a major challenge to limit temperature rises to 1.5 °C. Arguing that more renewable energy alone would not be enough, he agreed that a huge tree-planting project the size of the Amazon rainforest would be needed. He told the conference: “You can get to 1.5 °C, but not by just by pulling the same levers a little bit harder, because they are being pulled roughly as fast and as hard as we are currently imagining. What we think can be done is massive reforestation.” He added “It’s not what some people sometimes think: we’ll just do a little bit more solar, a bit more wind and we’ll get there.”

Going further, he stressed that meeting this challenge would not be commercially viable without major changes to government policies. He offered support to the UK government bringing forward its proposed ban on new petrol and diesel car sales. He said that an earlier date would ease investment decisions and shift consumer attitudes. In preparation for that, Shell has bought one of the UK’s biggest electricity and gas suppliers and invested in electric car infrastructure firms. BP did something similar. But he stressed that even though Shell is and will be investing more in renewables in future, its core business is and very much will be in oil and gas.

In fact he was adamant that gas will have a role to play even in a 1.5 °C world. That’s why the company has invested so much in gas. Shell has also put forward a credible scenario, SKY, which the company claims is a ‘technically possible but challenging pathway’ that can meet Paris Agreement goals.

At the same conference, Qatar Petroleum CEO Saad al-Kaabi said that: “We believe natural gas will continue to play a key role, not as a so-called transition fuel but rather in our view, a destination fuel.” He added that getting rid of oil and gas would require “a solution that is different from just renewables,” otherwise, “unless there is another way of getting there, it’s difficult to comprehend how we’ll achieve it.”

The oil and gas companies see natural gas playing a major role in global energy for decades to come. But companies such as Shell, BP, Total, Equinor and Eni are adapting to the need for cleaner energy by investing in renewables, low-carbon energy and electric vehicle technology.

The IPCC report backs the use of carbon pricing and CCS technology and the oil and gas companies support this as means by which gas can retain a foothold in future.

But an increasing risk for the fossil fuel sector is possible flight of capital. There is increasing pressure by activists and divestment campaigners on commercial and development banks, pension and sovereign wealth funds, and insurers to divest from the sector.

There is also the threat of increasing risk of litigation. In the Netherlands an appeals court decided to uphold a legal order for the government to cut the country’s greenhouse gas emissions much faster. Explaining the rationale behind this decision, the judge said: “Climate change is a grave danger. Any postponement of emissions reductions exacerbates the risks of climate change. The Dutch government cannot hide behind other countries’ emissions. It has an independent duty to reduce emissions from its own territory.” This is part of a wave of climate litigation around the world.

These developments are what prompted BP CEO Bob Dudley in his keynote address to the conference as ‘petroleum executive of the year,’ to say that calls for divestment from fossil fuel companies are a threat to global energy security. He added that despite the transition to a low-carbon world, both oil and gas are still crucial for meeting future energy demand.

He said that even though renewables are growing remarkably fast, they will only provide about a third of the global energy mix by 2040, adding that “The world will still need to meet the remaining two-thirds of demand.”

The energy sector has an obligation to ensure enough energy supplies are available for the world. Divestment will put this in risk. A move to tackle emissions should also address this part of the equation. The systemic risk to oil and gas companies is under-investment and inability to meet demand.

Dudley outlined why continued investment in the oil and gas industry is essential to meeting the dual challenge of providing billions of people with more energy while drastically lowering carbon emissions.

But Dudley also agrees that the IPCC report is a call for unprecedented changes in how the world consumes energy. He said: “Clearly it’s a call to action,” adding “not only oil and gas companies, but you need that in agriculture, you need that in steel production, you need that in people pushing the button on the wall to get electricity.”

Van Beurden said that reaching the 1.5 °C target would be a major challenge. Even though it is technically just about doable, “it would not be commercially viable under today’s regulations and policies and market designs, so things would have to change.”

Governments, not just energy firms, need to take the lead to achieve the IPCC targets to contain global warming, with policies that will change fuel and other energy consumption habits. Energy firms are quite willing to work with governments to achieve this. Dudley summed this up: “We can do this even faster and more efficiently with clearer, smarter policy signals from governments.”

Without a major shift in policies, energy demand and energy consumption habits will not change as proposed by IPCC. This process has already started, with a number of countries setting policy goals consistent with near net-zero emissions by 2050. But how to get there, while providing the levels of energy the world needs on demand, affordably and reliably, still needs to be worked out. In the meanwhile the oil companies see it as their obligation to continue providing the energy the world needs for as long as required.

Limitations

A limitation of the solutions to climate change proposed by IPCC is that to solve the problem the world would have to slow down growth – and no one wants to admit that. The social surveys cited above show that respondents are only prepared to make small lifestyle changes, which will not be sufficient to bring about the required level of change. Slowing down economic growth, especially in poorer and developing countries, could be a step too far for their politicians.

These solutions also rely on decoupling of energy from GDP growth. The IPCC report states that: "Energy demand lower than present day, together with strong growth in economic output until the end of the century, is found in scenarios with shifts to more sustainable energy, material, and food consumption patterns."

In other words, by switching energy sources and changing lifestyles, the world can achieve economic growth while using much less energy. But even though some degree of decoupling energy from GDP has taken place, last year and this year rapid global economic growth has partly reversed that, leading to increased energy consumption and emissions. With the world population expected to grow by over 2bn by 2050, keeping energy demand lower than today, particularly in Asia and Africa, would indeed be a major challenge.

In southeast Asia population growth – expected to increase by 20% by 2050 – and economic development, with average GDP increasing by about 3.5% per year, are leading to increasing energy demand, rising on average by 2% per year. Total energy consumption is forecast to roughly double between 2017 and 2050. Decoupling that from GDP growth will not be easy.

Switching to clean energy sources while maintaining economic growth and providing energy on demand remains a challenge.

The future

Much of the reaction to the IPCC report has centred on bolstering renewables. But their main use is in power generation and that transition is already well on the way, albeit it may need to be accelerated further. The main challenges in achieving what IPCC recommends are in all other energy sectors.

Widespread electrification, based on increasing use of renewables, may go some way in addressing some of the issues raised by IPCC. But even if it doubled by 2050, it would only account for 40% of global primary energy needs. The remainder would still need to come from other energy sources.

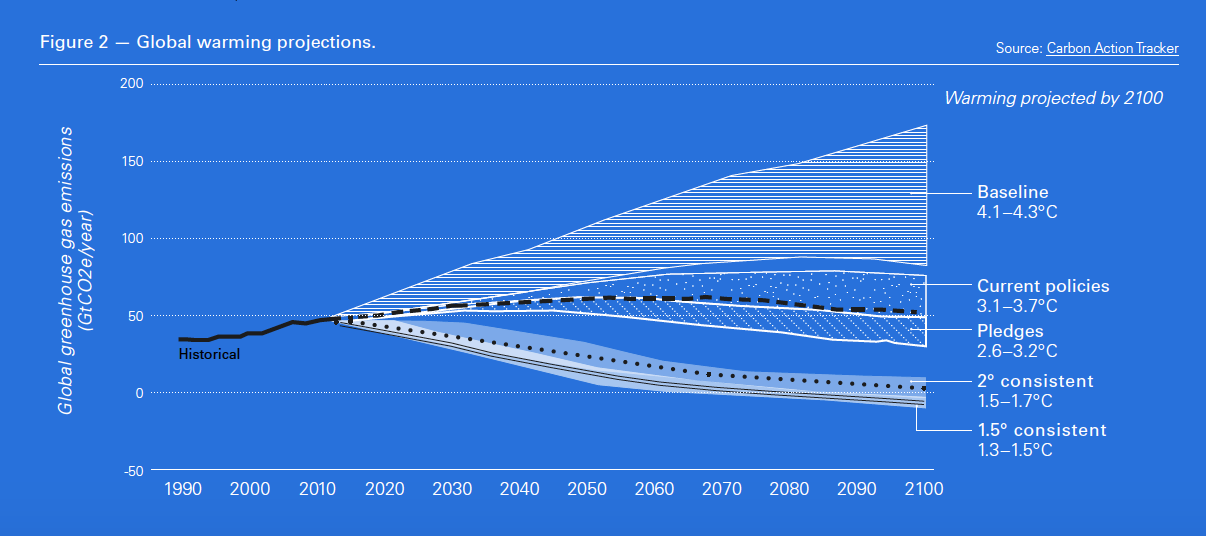

The European Climate Foundation (ECF) has proposed ideas on how to achieve this in its EU pathways to zero emissions study (Figure 4), stating though that it would require “significant policy intervention and investment.”

It proposes “putting more focus on how we operate as a society, innovation in our consumption patterns and increasing potential natural carbon sinks need to be combined with the more typical technical options such as energy efficiency, fuel shift, zero-carbon power production and electrification.”

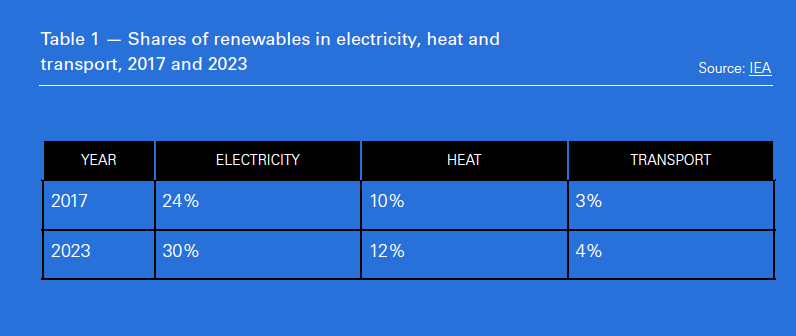

In its Renewables 2018 report, published this month, the IEA says that renewable energy will continue to grow rapidly over the next five years. It forecasts that by 2023 it will be providing close to 30% of power demand, compared with 24% in 2017 (Table 1). There will also be a modest increase in the use of renewables in heat and transport. The IEA says that this rapid growth is the result of policy changes and market developments in key countries, such as China and the EU. But however welcome these are, they are nowhere near what IPCC says is needed to limit global warming to 1.5 °C.

Nevertheless, it is policy that is needed to provide the direction on how best to respond to the IPCC recommendations.

Throughout this article, and almost in all publicity that followed release of the IPCC report, words such as ‘unprecedented, unparalleled, massive,’ have been used to describe the magnitude and pace of what needs to be done, if the world is to fully implement what IPCC recommends. Will this be achieved?

William Nordhaus, after been winning the 2018 Nobel prize for economics for his work on how the world economy and climate change interact, said: “There is basically no alternative to the market solution.” He added: “The most efficient remedy for problems caused by greenhouse gases is a global scheme of universally imposed carbon taxes,” but “policies are lagging very, very far – miles, miles, miles behind the science and what needs to be done.” Few in the oil and gas industry would disagree with this assessment.

William Nordhaus, after been winning the 2018 Nobel prize for economics for his work on how the world economy and climate change interact, said: “There is basically no alternative to the market solution.” He added: “The most efficient remedy for problems caused by greenhouse gases is a global scheme of universally imposed carbon taxes,” but “policies are lagging very, very far – miles, miles, miles behind the science and what needs to be done.” Few in the oil and gas industry would disagree with this assessment.

His co-winner, Paul Romer, said: “One problem today is that people think protecting the environment will be so costly and so hard that they want to ignore the problem and pretend it doesn’t exist,” but “once we begin to produce fewer carbon emissions we’ll be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as it was anticipated.” He added optimistically: “Humans are capable of amazing accomplishments if we set our minds to it.” There may be hope after all.