UN summit ratchets up pressure [NGW Magazine]

The head of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, led the 2019 Climate Action Summit September 23. Intended to boost the world’s ambition to implement the Paris Agreement, it had the strapline: “A race we can win, a race we must win.’ But the entry cost will be high.

In the lead up he set the tone by calling for an end to fossil fuel subsidies and no new coal plants to be built from 2020, putting a price on carbon emissions and asking all countries to plan for net-zero emissions by 2050.

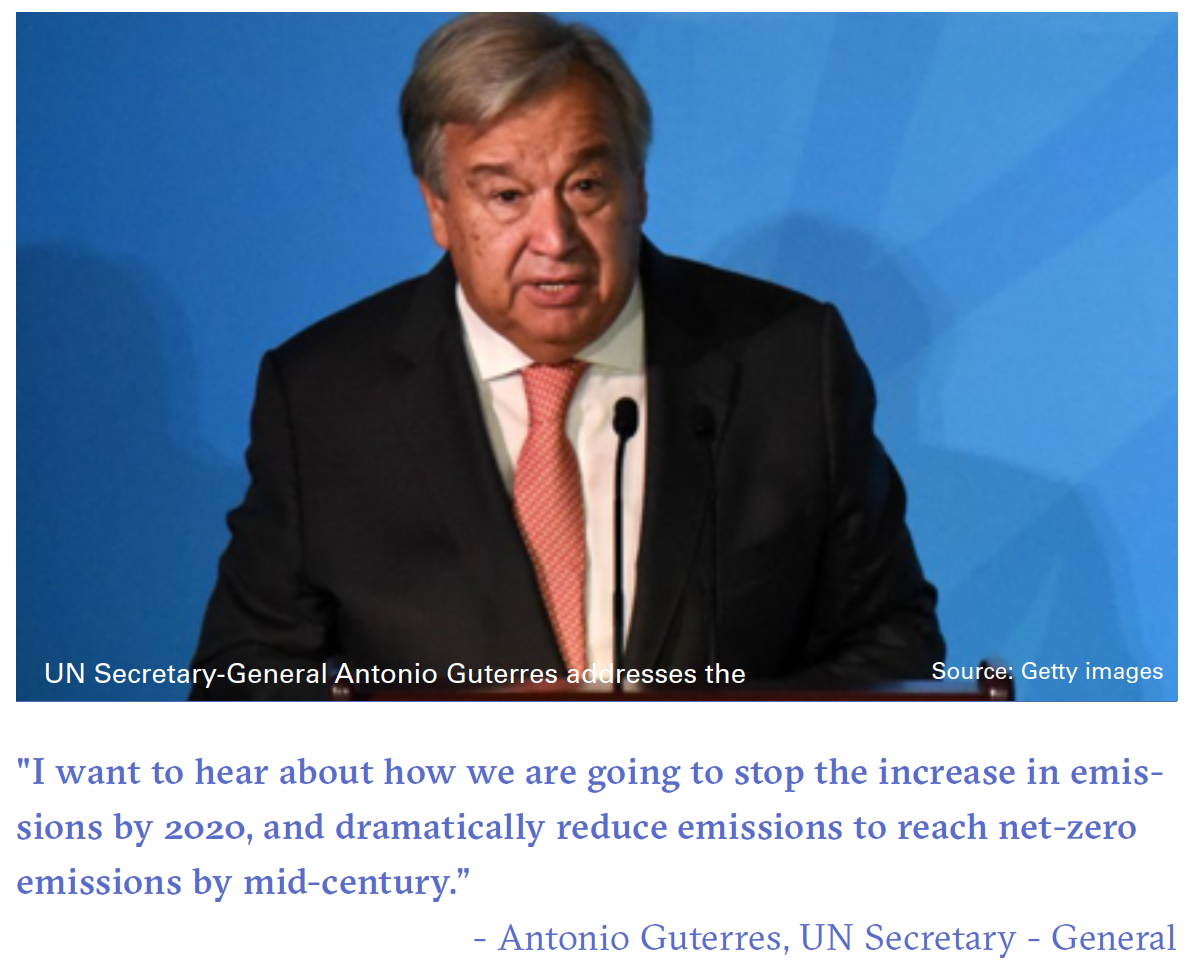

Announcing the summit, he asked for actions, not just words. He said: “I want to hear about how we are going to stop the increase in emissions by 2020, and dramatically reduce emissions to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century.” He requested all leaders to come “with concrete, realistic plans to enhance their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) by 2020, in line with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45% over the next decade, and to net zero emissions by 2050.”

Following the largest climate protests in history, on September 20, major announcements by government and private sector leaders boosted climate action momentum – leading to the Paris Agreement 2020 deadline to revise and ramp up national climate action plans – recognising that the pace of climate action must be rapidly accelerated.

As many as 77 countries committed to cut greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050 and 75 countries announced they will either boost their national action plans by 2020 or will have started the process of doing so.

There were nine inter-dependent action tracks, including:

- Energy transition: to focus on accelerating the shift away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy and energy efficiency and on creating stronger commitments from the hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel and cement

- Infrastructure, cities and local action: to focus on scaling up ambitious commitments on low-emission and resilient infrastructure, in particularly land-based transportation, buildings, water and waste systems and the requisite private and multilateral development bank financing

- Climate finance and carbon pricing: to make public and private finance flows consistent with low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development, and commitments to provide $100bn/year by 2020 to assist poorer countries.

Each track will be led by states and international organisations, including the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena), with specific objectives and action plans.

Energy transition

A key problem is raising private investment for the clean energy transition, and the solution is a regulatory framework that diverts money from fossil fuels – especially coal – towards renewable energy, energy efficiency, climate resilience and new innovative energy systems.

Market-driven public-private partnerships will also have to play a part, to bring in capital and technology in a safer way for the investor.

But a more fundamental question looking for an answer is how much more money will wealthy countries commit to funds needed to help the developing world during energy transition? Pledges are repeatedly being made but honoured more in the breach than the observance.

High-emitting sectors, including shipping, cooling, buildings and oil and gas production and so on, might be able to make more of the potential that hydrogen offers, although this is going to be expensive.

On the supply-side methane leakage, fossil fuel subsidy reform, solar innovation, energy storage innovation and carbon capture and storage (CCS) will all be explored together with the utilities sector.

Those hundreds of millions living now in fuel poverty will also benefit: their cooking and heating emits not only carbon dioxide but also the dangerous particulates that shorten lives today.

The UN sees these as key objectives and actions needed to deliver and achieve orderly and effective energy transition.

Oil and Gas CEO commitments

Thirteen oil and gas companies’ CEOs held an exclusive invitation-only forum with key stakeholders, environmentalists, academia, NGOs and government representatives September 23. It highlighted the dilemma of addressing growing demand for energy while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

While some environmental groups criticised the motives of those hosting the event, Mark Brownstein, senior vice-president of energy at the Environmental Defense Fund, said: “You make progress by talking to people that you don’t always agree with as well as people that you do agree with.… Climate change is a global challenge and we cannot afford to marginalise anyone.”

The forum was organized by the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGGI), an industry-supported organization whose members set targets to reduce methane emissions and gas flaring and support the move to a net-zero carbon emissions economy.

Introducing the meeting, BP CEO Bob Dudley said: “With collective action we can pool together our knowledge, experience, know-how and drive emission reduction and support the industry’s response to climate change.”

Brownstein said that “Human-caused methane emissions are driving about 25% of the warming that our planet is experiencing now, and oil and gas production is responsible for one third of that as a consequence of their global operations.” He called for the oil and gas industry to provide transparent data on what is being done to reduce such emissions.

This was taken up by Mike Wirth, CEO Chevron, who said: “Very soon nobody is going to be able to hide from methane leakage…because of satellites and other detection technologies.”

The CEO of Shell Ben van Beurden said it was clear that “ultimately”, the Paris Agreement is going to be met and gas could be a part of the solution.

But environmentally-friendly talk is cheap and the cost of reaching the goals is often ignored by those who set them. The CEO of French Total, Patrick Pouyanne, warned that “the only question is the pace at which society – not only us – will accept this transformation.”

The chief technology officer Saudi Aramco Ahmad Al Khowaiter said that the dual issue of rising energy needs and climate concerns is “something that we struggle with as an industry. It’s something we also see as critical…The need is so great and the time is so short.” He added that the company is diversifying across the board and, with transportation being the first low-hanging fruit, it also feels responsible to improve auto efficiency.

But if the pumps ran dry, society will be quick to blame the upstream. He said: “There is a kind of sense that this is the end of the industry. In fact, the world needs more oil.” This was repeated by the CEO of another state-owned company Eldar Saetre, of Norway’s Equinor, who said: “We’re going to need oil and gas for a long time. It has to be developed. We need to find more oil and gas.” Saetre also said flaring had to be reduced: “It is one of the biggest issues as it’s a waste and bad for the industry’s reputation…we can do something about it.”

Occidental Petroleum CEO Vicki Hollub said that CCUS technology is there but it has to be exploited on a broad scale, explaining its plans to build the world’s largest atmospheric carbon capture plant in the Permian Basin.

Collin O’Mara, the chief of the National Wildlife Federation, said there was no way to reach net-zero emissions without the technology, which is opposed by some as enabling the continued consumption of fossil fuels. He said “The time for purity is over…We need it all. We need every technology.”

Responding to the CEOs, Christiana Figueres, a former executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, said that the energy industry could “either put the nail in the coffin of all the global efforts on climate change or be the industry that develops and delivers the solution.”

Figueres said that serious investment in technology to capture and store carbon emissions underground is the only option right now for the oil industry to cut its climate change impact. Without serious change, the industry as-is will not survive beyond 30 years. She warned: “Frankly, my dear friends, I think you have a rough road ahead.”

Summit commitments

The summit succeeded in extracting many more commitments: leaders from government, business, and civil society – including 66 countries, 93 companies and more than 100 cities – announced practical actions to confront climate change and shift global response into higher gear.

Some of the major commitments made include:

- France announced that it would not enter into any trade agreement with countries that have policies that are counter to the Paris Agreement.

- Germany unveiled plans for carbon pricing for transport and heating and committed to carbon neutrality by 2050.

- 12 countries made financial commitments to the Green Climate Fund, the UN financial mechanism to assist developing countries and Norway, Germany, France and the UK have all doubled their existing contributions.

- India pledged to increase renewable energy capacity to 175 GW by 2022 and to further increasing it to 450 GW by 2030.

- China said it would cut emissions by over 12bn metric tons/yr and would pursue a path of high quality growth and low carbon development.

- The EU said at least a quarter of the next EU budget will be devoted to climate-related activities. In addition, the new European Commission committed to put into law net-zero emissions by 2050.

- The Russian Federation announced ratification of the Paris Agreement, bringing the total number of countries that have joined the Agreement to 187.

- Greece and Hungary pledged to phase-out coal by 2028 and 2030 respectively and Germany by 2038.

- Pakistan said it would plant more than 10bn trees over the next five years

- A group of the world’s largest asset-owners – responsible for directing more than $2 trillion in investments – committed to move to carbon-neutral investment portfolios by 2050.

- The shipping industry launched its Getting to Zero Coalition, which aims to deliver zero emission vessels by 2030.

- 87 major companies with a combined market capitalisation of over $2.3 trillion pledged to reduce emissions and align their businesses with a 1.5 °C future.

- 130 banks – one-third of the global banking sector – signed up to align their businesses with the Paris Agreement goals.

Many more pledges and commitments were made. Guterres said that while businesses were taking action, “the obstacle comes from governments. Governments are still reluctant to change regulation and adopt relevant policies . . . It’s much better to tax carbon than to tax income.”

That problem remains. Most of the major economies fell disappointingly short.

Perhaps that is why insurance companies are already pricing climate risk. John Haley, CEO of insurance company WillisTowers Watson, said infrastructure built in future must be climate resilient. He launched the Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment (CCRI), which will price climate risk and cause capital to flow to more resilient projects. By end of 2020, there will be methodology produced. They also plan to create ‘innovative investments’, such as ‘resilience bonds’.

Closing the Summit, Guterres said “You have delivered a boost in momentum, cooperation and ambition. But we have a long way to go…We need more concrete plans, more ambition from more countries and more businesses. We need all financial institutions, public and private, to choose, once and for all, the green economy.” But it remains to be seen how words will be converted into action during the 2020 ramping-up of national climate action plans.

The case for the oil and gas sector to be part of the world’s energy future is strong. But its social license to continue operating is increasingly being questioned – it needs to rise to the occasion and respond responsibly if it is to ensure a sustainable future. It also needs to overcome mistrust and make the case that it has a genuine desire to work towards achieving climate targets.

Challenges

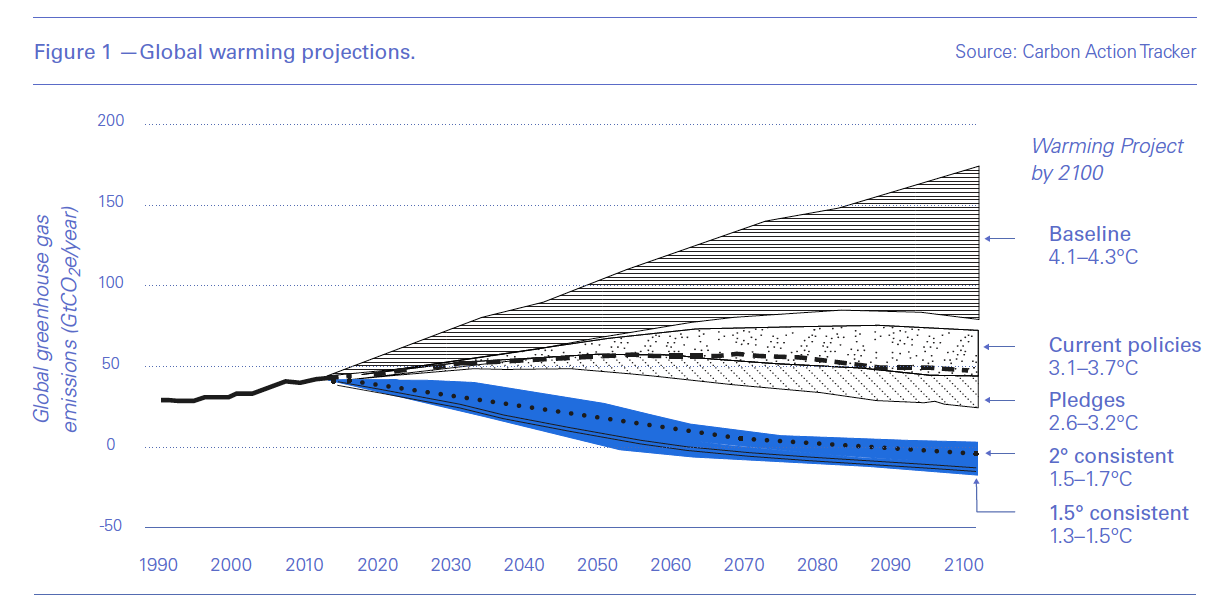

Guterres issued a clear message: time is rapidly running out (Figure 1). Given that many countries are barely achieving their NDCs, It will be a challenge to raise the bar for fighting climate change even further.

Even though India and China are not far from delivering their NDCs, they are still two of the largest carbon emitters in the world. Both are still heavily reliant on fossil fuels. Security of energy supplies and economic reasons mean that they continue being reliant on coal. Growing populations and aspiration of better standards of living mean more energy and likely more emissions. The question is how are they going to reconcile these conflicting demands?

China made commitments to cut emissions and India pledged to increase renewable energy capacity but both are still committed to coal.

In fact none of the three countries with the biggest coal expansion plans – India, China and Turkey – addressed their future commitments or made any pledges regarding coal use. In another if unsurprising setback, Poland announced early October that for energy security reasons it will prioritise curbing its reliance on Russian energy, meaning more domestic coal consumption.

Another question is how seriously are countries taking their own obligations under the Paris agreement? A 2018 UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report states that “Current commitments expressed in the NDCs are inadequate to bridge the emissions gap in 2030… to ensure global warming stays well below 2 °C and 1.5 ° [Figure 1]…if NDC ambitions are not increased before 2030, exceeding the 1.5 °C goal can no longer be avoided. Now more than ever, unprecedented and urgent action is required by all nations.”

At present, even the G20 countries are collectively not on track to meet their unconditional NDCs for 2030. This includes the EU.

In a letter to European Council president, Donald Tusk, Guterres said the EU should lead by example and reduce its emissions by 55% below 1990 levels by 2030. This is a much more ambitious target than the current 40% target. It is also one that Ursula von der Leyen, the next president of the European Commission, supports and has committed to the European Parliament to deliver it.

According to the UN Development Programme (UNDP) so far only 75 out of 187 Paris Agreement signatory nations, representing 37% of global carbon emissions, plan to ‘enhance’ their 2015 mitigation and/or adaptation efforts by 2020.

The US is not one of them. But if the Democrats win the presidential elections in the US, the changes they are proposing could shake the energy industry worldwide. They would ban fracking everywhere and immediately and impose 100% renewable and zero-emission energy in power generation by 2035, with potentially a huge impact on oil and gas during the next decade. All those new LNG export terminals might then need repurposing as import terminals. And without shale gas – and renewable intermittency still being a problem – coal would be back in vogue once more as a power generation fuel, setting back global emissions hugely as coal would also become much cheaper than gas in the US and in Asia.

But what the summit did not address is how to achieve the massive changes required, while keeping the lights on, their impact on energy security and how affordable would this be. This is more so in Asia, where increasingly most global energy is consumed, than in Europe.

As Guterres acknowledged, the transition would not be easy. “Limiting warming to 1.5 °C is still possible. But it will require fundamental transformations in all aspects of society – how we grow food, use land, fuel our transport and power our economies…There is a cost to everything. But the biggest cost is doing nothing.” Much remains to be done.