Uncertain Past, Uncertain Future: How Assumptions About The Past Shape Energy Transition Expectations

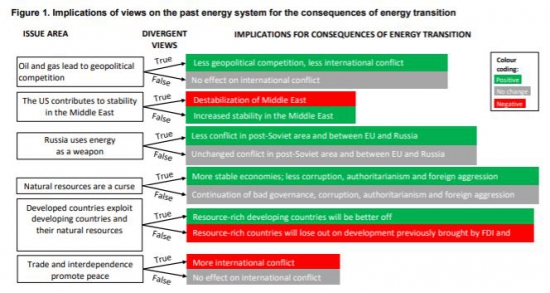

Many of these works conjecture boldly about how the replacement of fossil fuels by renewable energy will affect international affairs. However, many of these conjectures rest on unstated assumptions about the global energy system of the past, which is more contested than it is made out to be. Figure 1 presents six areas where one’s interpretation of past and current issues are decisive for how one thinks about the changes that will be wrought by the energy transition. The rest of this article reviews each of them.

Geopolitical competition over oil and gas

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

A common assertion in recent decades is that oil and gas resources are geopolitically important and therefore subject to intense international competition. From this perspective, the American invasions of Iraq were all about oil, African and Latin American countries are subject to intense competition between China and Western countries driven by competition over oil and other natural resources, and the Arctic is a hotspot of territorial rivalry.

This geopolitical mindset harks back to the classical works of Halford Mackinder, Rudolf Kjellén, and Friedrich Ratzel, whose names geopolitical enthusiasts like to invoke to give themselves historical weight and credibility. However, if one actually reads these classics, it is clear that they represent a simplistic and deterministic social science that no longer has much credibility.

Admittedly, geopolitical competition was decisive during the colonial era and the First and Second World Wars. Then, great powers engaged in continuously expanding, cumulative, winner-takes-all competition over strategically valuable natural resources and locations. The great power with the most men (territories), tanks (steel), and diesel (oil) had a good chance of winning. The more geopolitical advantages a country could amass, the more likely it was to prevail over its competitors further down the line. Hence the fierceness of the Battle of Stalingrad (which was located on the supply route for Caspian oil) and the bombing of Pearl Harbour (which was partly triggered by competition over South-East Asian natural resources, especially oil).

However, since the advent of the nuclear bomb, it is not clear that maximum access to oil would be as decisive in a direct military confrontation between great powers. Furthermore, the end of colonialism means that there are no more ‘white spots on the map’ to compete over. Occasionally it is still possible to occupy a territory, and some states can be made military or economic clients, but that is a far cry from the classical geopolitical race.

If oil has not had the geopolitical value during the post-war period that some have thought, the transition to renewable energy might not usher in the era of peace and goodwill between great-power states that someone seeing the world through a geopolitical lens might expect. By contrast, if the geopolitical interpretation of the recent decades does makes sense after all, a transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy should greatly reduce tensions in the international arena. The United States should lose interest in the Middle East, competition between China and Western countries over client states in Africa and Latin America should soften, and oil-fuelled geopolitical hotspots such as the Arctic, the Persian Gulf, and the Caspian and South China Seas should lose some of their lustre.

It is not necessary to draw a final conclusion here on who is right about past geopolitics, just to recognize that the role of geopolitics in the oil-based international energy system is contestable—and that one’s choice of perspective has implications for how one envisages the geopolitical consequences of the energy transition.

US engagement in the Middle East

The most important piece in the putative puzzle of petroleum geopolitics is the Persian Gulf and the wider Middle East and North Africa region. Here, another set of assumptions comes into play. Apart from the question of how robust the argument is that geopolitical interest in oil is a cause of American engagement in the region, there is also the question of what the consequences are of that engagement. Has the US been a stabilizing or destabilizing factor in the Middle East, or both? Has it contributed to more or less democracy among the Muslim states? Clearly, those are contentious questions. The views one adopts lay the premises for how one thinks about the consequences of declining Western interest in Middle Eastern oil and gas and whether it will entail more chaos or stability and more authoritarianism or democracy.

Russia’s energy weapon

The Russian Federation is seen by some as having used its natural gas resources as a foreign policy tool or even a weapon. Proponents of this viewpoint to not only the disruption of gas supplies to Ukraine and other countries straying from Russia’s orbit, but also the use of discounted energy supplies to entice countries to stay close to Moscow.

However, while many see Russia using its fossil fuel resources to maintain a semblance of the Soviet Union, others see the opposite: the modernization, increasingly commercial orientation, and independence of post-Soviet Russia. From this viewpoint, if Russia’s neighbours want to continue using Russian energy resources, they must now pay the real cost, and their reluctance and/or inability to do so—not any heavy-handedness on Russia’s part—is the real problem.

Which of these two opposing views one adopts has implications for how one thinks about the consequences of the energy transition for international affairs in the post-Communist area. Those who perceive that Russian has been using energy as a weapon might expect the energy transition to disarm Russia. Those who do not subscribe to this view will not expect to see much change in terms of international security, just the loss of an important source of revenue for Russia.

The resource curse

A vast literature sees natural resource wealth as a curse, bringing corruption, bad governance, authoritarianism, and domestic and international conflict. In many contexts it is taken for granted that the resource curse is a real phenomenon and constitutes a major obstacle to development in resource-rich countries.

However, there is also an antithetical literature, which has been growing since around 2008. It argues that much of the resource curse analysis has been based on flawed statistical analyses and that the curse does not exist. In this view, the problems that many resource-rich countries grapple with must be due to climate, culture, religion, colonialism, or something else.

Which of these perspectives one adopts influences how one thinks about the consequences for development of declining oil demand. From the resource-curse perspective, authoritarian and/or underdeveloped petroleum-exporting countries may be freed of a burden and finally flower. Countries such as Angola, Russia, and Saudi Arabia should then have a greater chance to become democratic, reduce corruption, and maintain peace with their neighbours. By contrast, from the resource-curse-sceptic perspective, energy transition should not bring much change in this area.

Dependency theory

Dependency theory used to be widely taught in Western universities in various guises, including neo-Marxism, world systems theory, and periphery capitalism. The central idea of dependency theory is that ‘central’ (wealthy, Western) states exploit ‘peripheral’ (poor, non-Western) states, draining their natural resources and ensuring by political, military, and economic means that they are unable to develop. Obviously, dependency theory never gained much popularity among people holding freemarket, pro-Western views, who see underdevelopment as mainly caused by internal problems such as bad governance, corruption, weak institutions, and authoritarianism.

After the collapse of Communism, dependency theory lost much of its popularity. However, many people—including academics—continue to believe explicitly or implicitly that poor countries are poor because they are subjugated and exploited by wealthy countries. From this perspective, a transition to renewable energy and the concomitant reduced interest in the fossil fuel resources of developing countries should improve the lot of poor countries, as wealthy countries will have less interest in exploiting them. By contrast, those who do not see dependency theory as having much explanatory power might not expect the energy transition to unlock developing countries’ supposedly thwarted powers of self-determination.

Potential of trade and interdependence to promote peace

It has frequently been argued that globalization and growing trade and interdependence between countries promotes peace, for example by Keohane and Nye in their international-relations classic ‘Power and interdependence’. They envisaged that growing trade would create multiple ‘channels’ between countries while also reducing the importance of war in international affairs, leading to greater emphasis on economic tools and relations and opening the field to a more diverse set of actors. This liberal argument was energy-centred from the start and was thought to be supported by the oil crisis of 1973. It was intended as a critique of realist approaches to international relations, in which military force and physical resources had primacy.

Both perspectives live on today and provide opposing starting points for interpreting the consequences of the energy transition. From a realist perspective, the transition should reduce international tension. As countries become ‘prosumers’ that produce and consume their own energy from domestic renewable resources, they should become less dependent on the world’s hydrocarbon resources and should therefore have less reason to compete over them.

By contrast, from the liberal perspective of complex interdependency, growing reliance on domestic renewable energy resources should increase the risk of international conflict, as prosumer countries will be less dependent on one another and have fewer interlinkages to dampen their bellicosity. Peace-loving, pro-renewables liberals may find this counter-intuitive, but it is the result of a linear extension of the logic of complex interdependence to the clean-energy era.

Conclusion

These points indicate that existing projections of the consequences of the energy transition are more uncertain than they appear. But they also have implications for scenario-building, prediction, and foresight studies more broadly. Predicting future developments and events is challenging even when one agrees on the past. When the past is open to conflicting interpretations, prediction is yet more difficult. More attention needs to be paid to how interpretations of the past and present shape our predictions of the future, both regarding the geopolitics of the energy transition and beyond.

Originally publishes by the Oxford Institute For Energy Studies.