US LNG exports face bottlenecks [Gas in Transition]

US president Joe Biden’s pledge to support Europe with increased LNG exports in response to the rapid reduction in Russian gas supplies is being threatened by a number of factors, with pipeline permitting at the top of the list. Cumbersome environmental laws and increased litigation are making approvals of the required new infrastructure a major challenge, threatening to be a bottleneck to US LNG exports.

The US has been setting new records of natural gas production that could help out with greater LNG exports to Europe. But this depends on how much gas LNG plants can get out of the producing regions, such as the Appalachian region and West Texas, with new gas pipeline projects facing innumerable obstacles. Lengthy federal environmental reviews, often subject to legal challenges, on average take three to four years to complete. Legal and regulatory challenges are also slowing renewable energy projects.

Following a number of critical court rulings that it can no longer ignore the climate and environmental justice impacts of the projects it approves, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) voted in February to “overhaul the certification process for new gas pipelines, providing for greater scrutiny of the economic need for projects, as well as their impacts on the environment, communities and landowners.” For the first time, the process explicitly requires a “climate evaluation that would calculate emissions not just from the pipeline itself but potentially also from the upstream drilling process and downstream burning of the fuel.”

As a result of these changes, gas pipeline proposal reviews would take into account the project’s effect on climate change, consider a “wider set of impacts on landowners and environmental justice communities, and scrutinise the economic need for a project beyond its contracts with shippers.” These changes would make pending and new pipeline approvals even more difficult to secure.

However, with demand for US LNG on the increase and following an outcry from the oil and gas sector and legislators, the FERC backtracked in March and agreed to “recategorize the new policies as drafts that will only apply to future projects.” It invited additional comments by April 25 and reply comments by May 25, but did not indicate when revised policy statements might be issued. Clearly, though, the FERC has initiated a new era in pipeline certification and those involved not only need to pay careful attention, but ignore them at their peril.

And if that was not enough, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published in September a new proposal for GHG and methane emissions reporting that, once approved, is expected to have a substantial impact, “hitting pipelines hard”. This would lead to drastic “increases in natural gas sector measuring, calculation and reporting requirements for methane” and would also “serve as a stimulus for emissions reductions of methane from compressors.”

Since taking over, the Biden administration has restored “stricter environmental standards that were in effect during the Obama administration” for approving new infrastructure projects and is requiring the permitting approval process to include consideration of “how such projects might affect climate change.”

In addition to federal agencies, state and local governments also have permitting authority, adding more layers of bureaucracy, complexity and delay.

These new policies are likely to slow down the permitting process even further. On the other hand, environmental groups believe that they will accelerate transition to low-carbon energy sources with lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Litigation

This is where the greatest challenge to gas pipeline permitting in the US lies.

Environmentalists and climate activists are making heavy, and organised, use of US courts to delay, obstruct and even stop construction of new pipelines, driven by concerns that these will lock reliance on fossil fuels for years to come, but seemingly unconcerned about the impact on security of energy supplies and prices.

They also target insurers, convinced that if they stop the insurance, they can stop the pipeline.

They rely on and use stricter environmental regulations to challenge oil and gas projects in the belief that this will drive a faster transition to renewables, even if the required low-carbon technology to ensure on-demand, reliable and affordable energy is still being developed.

Essentially, they raise multiple legal challenges at every step of the permitting process costing project developers millions of dollars over many years. Many projects, however much needed they are, do not succeed to come out of these intact and increasingly fewer are even trying.

Litigation has been successful in stopping some major gas pipeline projects, such as the 600-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline, that would have transported gas from West Virginia to North Carolina, the 193-km PennEast Pipeline from Pennsylvania to New Jersey and the 195-km Constitution pipeline, from northeast Pennsylvania to central New York. They have also made life very difficult for the 483-km Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) in Virginia, even though this is over 90% complete. This has become central to Senator Manchin’s ‘Energy Permitting Provisions’ deal.

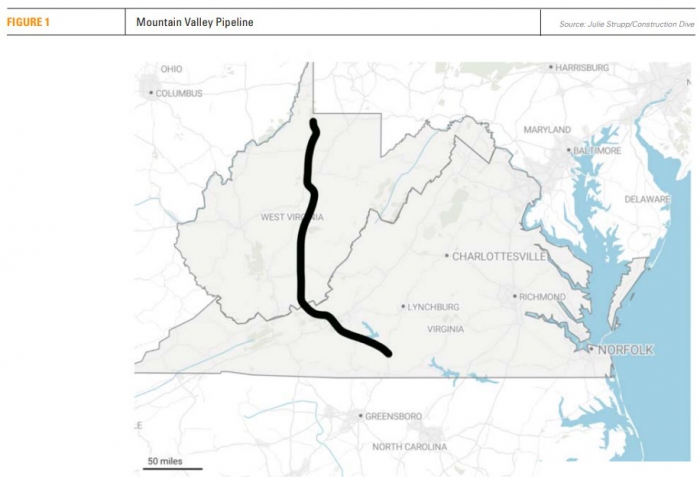

MVP is an important pipeline for the gas industry, designed to transport 2bn ft3/day Appalachian shale gas, extracted from the Marcellus and Utica Shale formations, to the Mid- and South Atlantic regions in eastern US (see figure 1). The formal application was filed with the FERC in October 2015 for approval to construct and construction started in early 2018. But ever since it has been beset by legal challenges that have delayed its construction and have contributed to an escalation of costs from an initial estimate of $3.5bn to $6.6bn now, with completion expected in 2023, five years later than planned. And it still needs permits to cross water bodies and wetlands. There are even question marks whether the pipeline will ever be finished at all.

The tribulations this pipeline has been going through epitomise the subject of this article.

Senator Manchin’s deal

In return for voting for the administration’s cherished climate change and energy security legislation, the ‘Inflation Reduction Act’ (IRA), Democrat Senator Joe Manchin struck a deal with the Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer to secure passage of crucial energy permitting reform legislation in September, by attaching it to the must-pass short-term federal spending bill that must be approved by September 30.

The deal attempts to set maximum timelines for permitting reviews of major energy infrastructure projects, not just for pipelines, but also for electrical transmission lines and generally of projects designated of “strategic national importance”, and to address excessive litigation delays, by “setting and enforcing reasonable schedules and deadlines.” It proposes limiting permit reviews to two-years to fast-track projects.

Specifically, the deal pushes completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, requiring “relevant agencies to take all necessary actions to permit the construction and operation of the Pipeline” and give federal courts “jurisdiction over any further litigation.”

Manchin claims that the pipeline would help “bring down natural gas prices that are adding to inflation…and [help] with LNG exports.”

Recently, a Bank of America research report makes the point that inadequate transmission is a big challenge for the envisioned clean energy growth and sees merit in the deal. It states “There is hope that permitting reform talks could help streamline the review process for infrastructure projects essential to the renewable power buildout."

However, the deal is facing challenges by both Democrat and Republican senators and approval is far from certain. But even though a number of Democrats have expressed their opposition, it is uncertain that such opposition would be sufficient to sink it altogether. In the meanwhile, the White House confirmed on September 12 that Biden is “committed” to the deal, as are Congressional Democrat leaders.

But legal experts believe that even if this passes, challenges to accelerating permitting of infrastructure projects will not go away. Activists and NGOs say they are determined to carry on fighting oil and gas projects.

Bottlenecks

Increasingly the FERC, the EPA and other federal agencies are driving the environmental and climate agenda, making permitting of new gas pipelines, and of fossil fuel infrastructure in general, that much more onerous and difficult. However, there is a backlash, with accusations that these agencies are “overreaching”. Nevertheless, the outcome is that approval of new pipeline projects is becoming more complicated, open to more litigation, taking longer and often leading to abandonment.

Even though FERC chairman, Richard Glick, is convinced that “these policy statements will provide project developers, consumers, landowners, and residents of impacted communities—and the commission itself—with a more legally durable path forward,” many pipeline developers disagree.

Clearly, the current highly litigious and dysfunctional system in the US is problematic. It may not be thwarted by any new policies, continuing to cause delays and cost escalation that make construction of new pipelines increasingly challenging.

In addition, with Biden committed to a climate change agenda, his Administration is unlikely to take proactive action to accelerate pipeline permitting.

In addition, with Biden committed to a climate change agenda, his Administration is unlikely to take proactive action to accelerate pipeline permitting.

As a result, US’ prolific shale gas basins are becoming increasingly constrained in evacuating the gas to the LNG plants on the coast for liquefaction and export. Without new takeaway pipelines, growth in shale gas production is slowing down at a time when demand for US LNG is at its peak and still rising, as a substitute for Russian gas, especially in Europe driven by energy security concerns.

So, it remains on Manchin’s permitting deal to remove the bottlenecks and facilitate expansion of the US natural gas transmission system to accommodate increased shale gas production.

If it succeeds, there will be hope that future permit applications involving projects that would help support LNG exports, will receive timely FERC approvals while at the same time ensuring that environmental reviews can withstand legal challenges.