Uzbek GTL plant reaches the finish line [Gas in Transition]

Uzbekistan ended last year by completing a state-of-the-art gas-to-liquids (GTL) complex, which the government says will save $1bn in annual fuel import bills and help in the country’s quest to maximise the economic benefit of its natural gas reserves.

GTL technology, involving the production of synthetic fuels from natural gas, is considered somewhat of a niche, and today only a handful of countries host such facilities. Essentially, it only makes economic sense in certain regions, where natural gas is cheap and conventional oil-based fuels are expensive to obtain. But Uzbekistan, with its significant gas reserves and logistical problems obtaining oil, fits the bill.

Uzbekistan boasts nearly 30 trillion ft3 in proven gas reserves, according to BP. And while neighbouring Turkmenistan, endowed with far greater resources, has sought to send most of its gas abroad, Uzbekistan wants to add value to its gas by using as much of it as possible internally, including for power generation, the development of petrochemicals and fertilisers, and for synthetic fuel production. The country currently ships gas to China and Russia, but plans to phase out these exports completely over the next few years.

Uzbekistan has also struggled for years with intermittent vehicle fuel shortages, which have created a major drag on its economy, and led to public discontent and at times anti-government protests. The country has three oil refineries, but they require upgrades and operate at only a fraction of their nameplate capacity. The issue is that Uzbekistan cannot find an economic means of importing enough crude oil, while its domestic output continues to slide. This has left it reliant on imports, mostly from Russia, although the GTL plant offers an alternative.

Import replacement

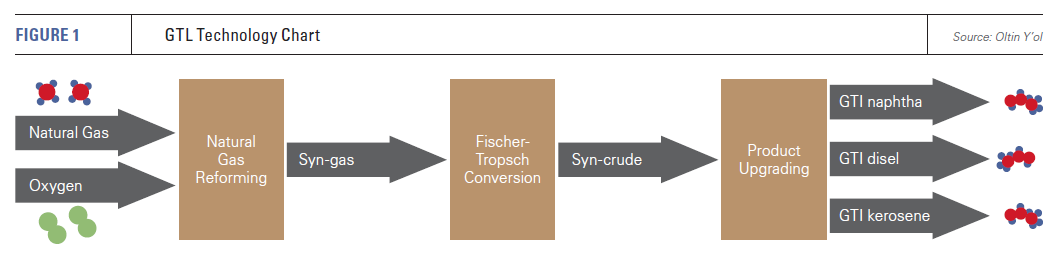

The government describes Uzbekistan GTL, built at a cost of $3.6bn in Uzbekistan’s southeast Qashqadaryo region, as one of the largest and most advanced plants of its kind in the world. At full capacity, it will convert some 3.6bn m3 of natural gas each year into more than 1.5mn metric tons of synthetic fuels, including diesel, naphtha, kerosene and LPG.

These fuels not only have “high added value,” but they also result in fewer emissions than oil-based equivalents, the facility’s general director, Fakhritdin Abdurasulov, tells NGW. The synthetic diesel that is produced contains nearly zero sulphur, he says, and has various other operational advantages over the oil-derived alternative, such as improved thermal stability and reduced engine noise.

This diesel will be used in Uzbekistan’s agricultural sector, a major generator of foreign currency, as well as in transport and mining. Meanwhile, the facility’s naphtha will be sent to the nearby Shurtan petrochemicals complex, where it will be used as feedstock for ethylene and propylene, which are used primarily to produce plastics.

Kerosene is a component in jet fuel, and again, when produced synthetically from gas, emits less sulphur and particulate matter during combustion. Supplies from the GTL plant will help Uzbekistan establish itself as a hub for international air travel, harnessing its position between Asia and Europe. Finally, the LPG can be used in vehicles and for heating and cooking.

“Because of a lack of local raw materials for processing, annually there is a shortage of automotive and aviation fuel on the domestic market,” Abdurasulov says. “Uzbekistan GTL will help end the import of liquid hydrocarbons, which will lead to Uzbekistan achieving energy independence.”

A long road to realisation

The government has hailed the plant’s completion as an important milestone in Uzbekistan’s economic development, estimating it will bring in over $4bn in tax revenues over the course of its operational life. But the project’s road to realisation was considerably long, highlighting the difficulty that such grand investments can face in Central Asia.

Work began well over a decade ago, with state-owned project operator Uzbekneftegaz (UNG) signing a heads of agreement on its development in 2008 with South Africa’s Sasol, an early pioneer in GTL technology, and Malaysia’s Petronas. In 2009, they agreed to form an equal-shares joint venture.

The group started their search for financing in 2013, with Uzbekistan reaching out to export credit agencies (ECAs) from Asia and Europe. But a setback came in 2016, when Sasol pulled out to focus on other investments elsewhere such as its Lake Charles ethane cracker in the US. Petronas later quit to pursue new upstream and LNG investments in Malaysia. Investors withdrew from a number of projects in Central Asia at that time, as the slump in commodity prices hit the resource-dependent region hard.

UNG continued with the project alone, and according to Uzbekistan’s energy ministry, spent time in talks with contractors to find ways of lowering the cost, resulting in a cut in expenditure of $700mn. The government also opted for sovereign rather than limited resource financing to help further bring down costs.

The breakthrough came in December 2018, when Uzbekistan secured over $2.3bn in funding from China Development Bank, South Korean ECAs Kexim and K-Sure and Russian banks Gazprombank and Roseximbank, as well as other lenders.

Though complete, the GTL plant is not yet up and running, and it is not expected to start producing commercial volumes of fuel until the second quarter of the year, according to Abdurasulov. It is not slated to reach full capacity on a stable basis until 2023-2024.

Products from the plant will be sold domestically on an exchange, Abdurasulov says, while negotiations are underway with foreign partners, including large traders and manufacturers, for product exports.

As Uzbekistan expands the role of gas in its economy, though, domestic supply will need to keep up, and the GTL plant’s launch will only add to the country’s demand needs. Previous targets for output that the regime has set in recent years have not lived up to expectations. At the same time, the country needs to modernise its ageing gas pipeline network, much of which was built 50 years ago. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated in 2019 that the poor state of this network resulted in technical losses of up to 15% of total gas supply.