Venture capitalists and corporates turn to hydrogen [GasTransitions]

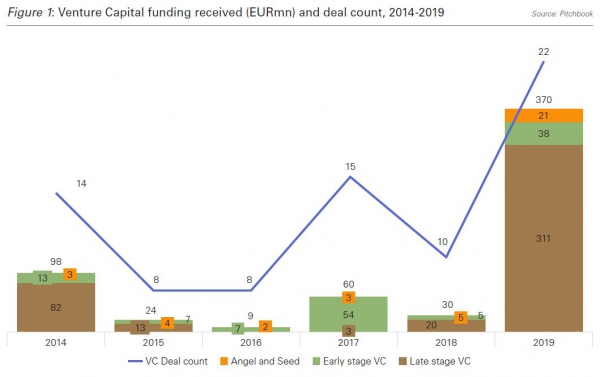

The renewed interest in hydrogen by the private sector is illustrated through the recent strong growth in Venture Capital funding (EUR 591m during 2014-2019), see figure 1. The Venture Capital funding rounds are primarily in the later investment stages, which means investments are flowing to more established ventures in the market.

In conjunction with Venture Capital funding, we have seen significant growth in corporate led deals. In 2017, we saw Amazon provide $600 million to Plug Power for further development of their fuel cell technology, which is intended to be implemented in Amazon’s warehouses via hydrogen powered forklifts.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The recent increase in corporate-led deals suggests that the hydrogen ecosystem is poised for further growth, as notably the strategies of corporates are cooperative and value adding, as opposed to competitive and value capturing. Such strategies are essential to mitigating the various risks of entering such an ecosystem.

How to mitigate risk in an emerging technology market

Risks facing corporates from emerging technology markets are two-sided. On the one hand there is the financial risk of investing in the technology, which after passing the research phase must meet commercial requirements in order to scale. On the other hand there is the risk of missing the opportunity, as in the case of automotive OEMs missing the recent electrification trend and needing to play a (very) expensive game of catch-up.

Forming alliances has become the standard way of alleviating these risks, as recently we have noticed an uptake in corporates engaging in the hydrogen ecosystem through partnerships and investments, following three broad risk mitigation trends.

Firstly, corporates are combining in-kind services with cash when executing investments. An illustrative recent investment was in September 2019 when Nikola Motor Company raised $100 million in Series D venture funding from CNH Industrial, in addition to $150 million in services, including product development, engineering and technical assistance. Limiting the immediate cash investment may be more palatable for corporates, in addition to increasing their influence on the development of the technology and range of applications. Investment strategies in this regard serve to ‘externalise’ R&D development.

Secondly, we are seeing investment diversification through multiple venturing style investments across the hydrogen sector. Examples of this approach are the venturing activities of Hyundai and Robert Bosch. Hyundai closed one investment in 2020 for Hydrogenious LOHC, a hydrogen storage company and three hydrogen investments in 2019: Impact Coatings, which created a fuel cell coating solution, H2Pro, which developed an E-TAC water splitting technology and GRZ, a hydrogen storage company.

Robert Bosch acquired a 13% stake in the stationary fuel cell company Powercell Sweden in 2019 and a 14% stake in the Solid Oxide Fuelcell (SOFC) company Ceres Power in 2020. This diversification within an ecosystem creates potential for synergies and knowledge sharing as they position themselves across the hydrogen value chain.

Thirdly, partnerships are being formed both across and within industries. This mitigates the first mover risk and serves to grow confidence in participating in the ecosystem for all types of companies. One such example is Faurecia (a global leader in automotive technology), which formed a Joint Venture with Michelin to bring together Faurecia’s hydrogen storage capabilities and Michelin’s fuel cell capabilities, which were developed through its Symbio acquisition of 2019. This partnership created a hydrogen centre of excellence and signals both firms’ ambitions to be dominant players in the hydrogen economy by specializing across the value chain.

We anticipate that when the market becomes more established, you will see a next wave of M&A with new leaders emerging, and the ones who missed out acquiring the others. All this renewed attention to hydrogen should ensure that the costs of green hydrogen will experience the same declining curve that solar and wind electricity experienced. This requires scaling up of electrolysers needed to produce hydrogen.

This is exactly what we are seeing happening at the moment. Internationally, more than 8 GW electrolyser capacity has now been announced, a tripling in the past 5 months. In the Netherlands, where we are based, we see big ambitions under the country’s national climate agreement: 3-4 GW of electrolyser capacity in 2030. Due to this increase in scale, the Dutch government expects the costs of green hydrogen to decrease by as much as 50-60% in the next 10 years.

Where does hydrogen have its largest potential?

Despite this upsurge in interest in hydrogen, we must not lose sight of where hydrogen can make a significant contribution, and where investment in the application will prove to be a bottomless pit. For example, (green) hydrogen in passenger transport will likely remain a niche (although total numbers can still be substantial) because electric cars are now so cheap that it is difficult to catch up with this competitive advantage.

Furthermore, in the built environment sufficient alternatives are available. In that sector hydrogen will only find application in those geographies where heat demand is high, insulation is poor and an existing gas network can be used; likely the case in old city centres. The vast majority of houses and offices will see increased electrification and in others district heating or biomass will provide the required space heating and warm water. Hydrogen in the built environment will therefore remain a niche for the longer term. Blending of hydrogen, possible up to 10-20% in the Netherlands without major adjustments, could be an intermediate solution especially when combined with Guarantee of Origin certification.

Hydrogen will have the most impact in sectors that are hard to electrify and where the technology and infrastructure constraints can be overcome. In mobility, long-haul trucking will have the most potential because its energy to weight ratio is superior to that of batteries. The mass-application of hydrogen in personal transport would be helpful to get the costs of fuel cells and refueling infrastructure down, thus supporting applications in the more promising segments such as long-haul trucking or busses.

Synthetic hydrocarbon fuels, produced with hydrogen, will enable the decarbonization of aviation and marine transport, but only beyond 2040. Hydrogen will also likely play an important role in integrating ever larger shares of renewable electricity, by providing a transport and buffer medium.

Surprise

However, the largest volumes and gains for the climate on the short term can be achieved in industry, to decarbonize chemical and high temperature processes such as steel making. Many industrial processes already use hydrogen and application of blue hydrogen (hydrogen production from natural gas in combination with carbon capture and sequestration), could be an intermediate step to the use of green hydrogen. It is therefore a good idea to connect industrial clusters, which is what Gasunie in the Netherlands is planning to do.

In this respect, the Netherlands is in a unique position because in most countries gas production is increasing instead of diminishing. The reduction in gas production in the Netherlands, as a result of the imminent closure of the Groningen field, means that transport capacity will be available to transport hydrogen. Therefore, it could be that one surprise – stopping Groningen gas production – will lead to the next surprise: large-scale application of green hydrogen in the Netherlands. There are still plenty of hurdles to overcome, but if politics and business take further steps together in the coming years, hydrogen could become the surprise of the 2020s.

Many companies, analysts and market watchers have been surprised by the enormous cost reductions solar, wind and even batteries have seen over the last decade. The conditions are ready for green hydrogen to take the same fast track towards large scale commercialisation. To make use of this development, companies need to get in the market now to gain expertise, understand the mechanisms at play, and know what to focus on. They need the partners to hedge the risks and regulatory presence to steer discussions.

Deloitte’s Global “Future of Energy” lead Eric Vennix, a partner who also heads the Energy, Resources & Industrials industry within Deloitte North and South Europe, contributed to this article.

This article was first published on the website of Deloitte and is republished here with permission.