Vietnam to see steady growth in LNG demand [Gas in Transition]

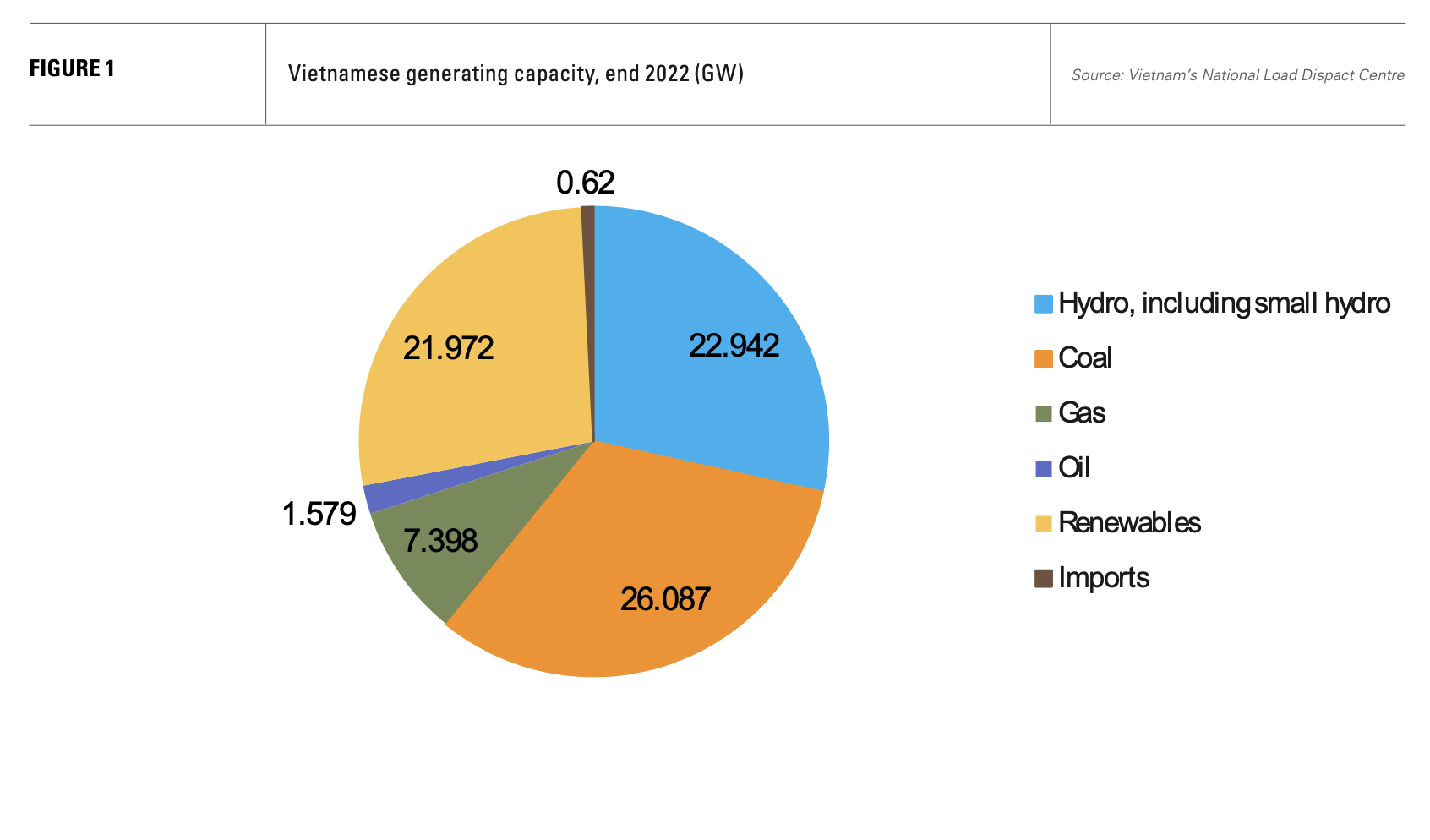

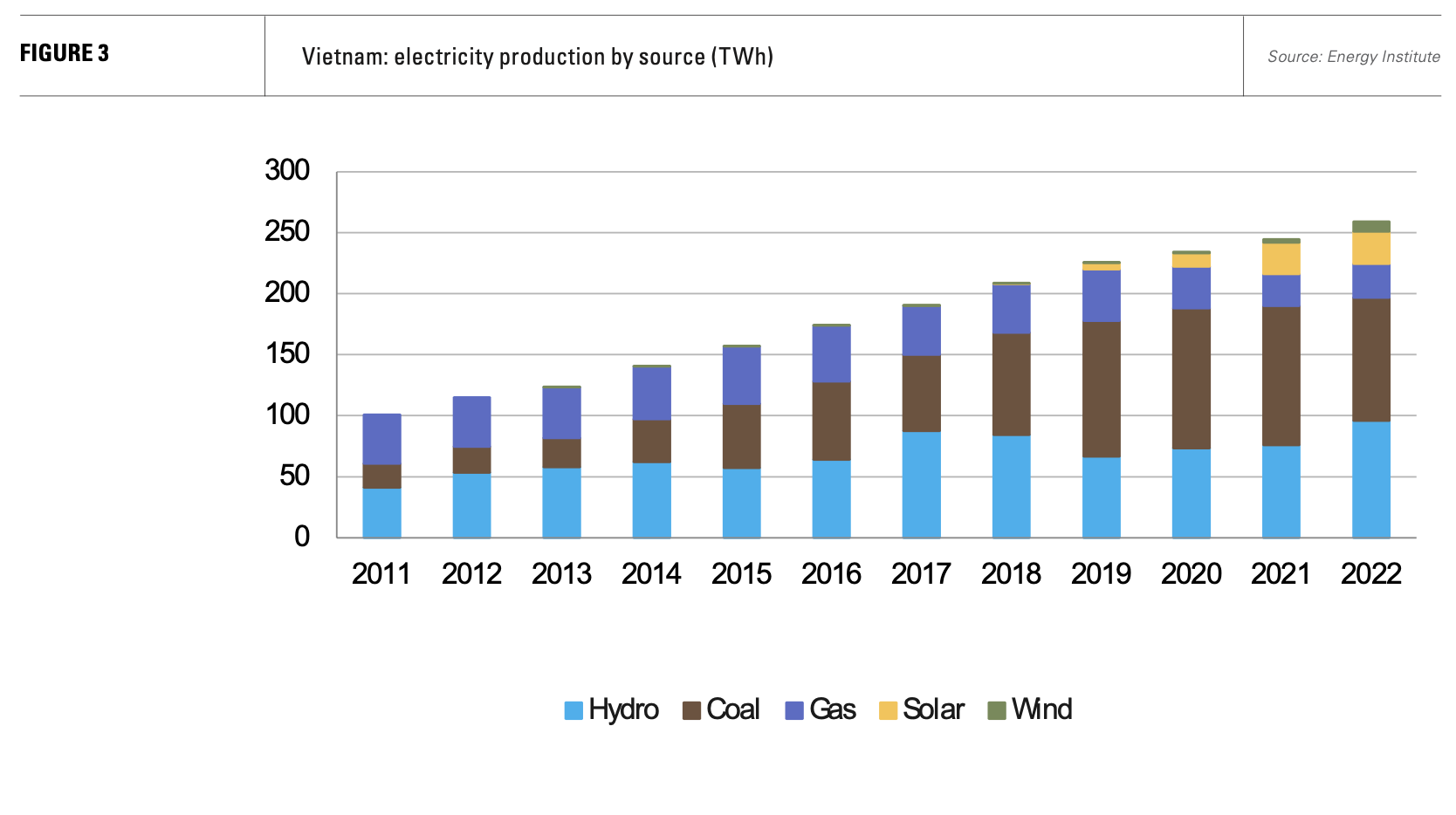

Vietnam’s primary challenge is to meet high levels of electricity demand growth and simultaneously reduce and eventually eradicate its current heavy dependency on coal, which last year accounted for 42% of electricity generation (see figure 1).

Power demand rose 6.2% in 2022 and, in November 2023, was running 7.1% higher year on year. GDP growth is forecast by the World Bank at 5.5% this year, increasing to 6.0% in 2025.

Vietnam is sucking in large amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI), which is boosting its economy. FDI amounted to $36.6bn in 2023, a jump of 32.1% from 2022. Singapore was the largest investor, followed by Japan, Hong Kong and then China. China registered the largest number of new projects, with more than a fifth of the total. The processing and manufacturing sector accounted for 64.2% of the FDI, up almost 40% from 2022.

At the same time, Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US has ballooned. March data showed a monthly surplus of $10bn, the US’s third largest behind China and Mexico. In 2023, Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US was $104.6bn, more than treble the level of 2016.

The surplus has grown as the US has raised its import tariffs on Chinese goods. Investors appear to be using the country as an offshore location for the final assembly of products which circumvents tariffs placed on direct exports from China to the US.

In May, Washington announced large tariff increases on a wide range of Chinese goods from steel and aluminium to semiconductors, solar cells, batteries and electric vehicles. An unintended effect of this policy will be to reinforce the current trend of investment in Vietnam as an entry point for Asian exports to the US market, and, as a consequence, support the country’s strong rise in demand for energy.

2nd LNG terminal takes shape

Vietnam may not reach 30mn t/yr of LNG demand by 2030, but the fuel will become an important part of the fast-growing country’s energy mix.

The country’s first LNG cargo arrived in July last year to commission the Thi Vai regasification terminal, which is majority-owned by state company PetroVietnam. Thi Vai has a capacity of 1mn t/yr, but there are plans to expand this to 3mn t/yr later this decade. The country’s second import facility, Cai Mep LNG, started its commissioning phase in May and should start commercial operations in September, according to Singapore’s AG&P LNG. AG&P has a 49% stake in the 3mn t/yr terminal, partnering majority owner Vietnam’s Hai Linh Co. Both facilities are in Ba Ria Vung Tau province.

However, LNG no longer holds quite the central position in Vietnamese energy policy that it once did. It now represents more of a flexible gap filler should other policies fail to deliver. The three central policy pillars are: a reduction in coal use; an increase in domestic gas supply; and the accelerated construction of renewable energy capacity, notably offshore wind.

The government adopted a net zero greenhouse gas emissions target in 2021 and subsequently amended its power development plant, known as PDP8. Under this plan, total power capacity is to increase from 80.5 GW at the end of 2022 to 146 GW by 2030.

Coal-fired generation is expected to rise from 26 GW to 30 GW, but its percentage share of generation is expected to fall from 34% to 27%. Expansion of coal-fired generation has been limited to projects already approved under the revised PDP7. By 2050, coal should be completely phased out of the Vietnamese power system. Meanwhile, plans for the country’s first nuclear plants have been cancelled.

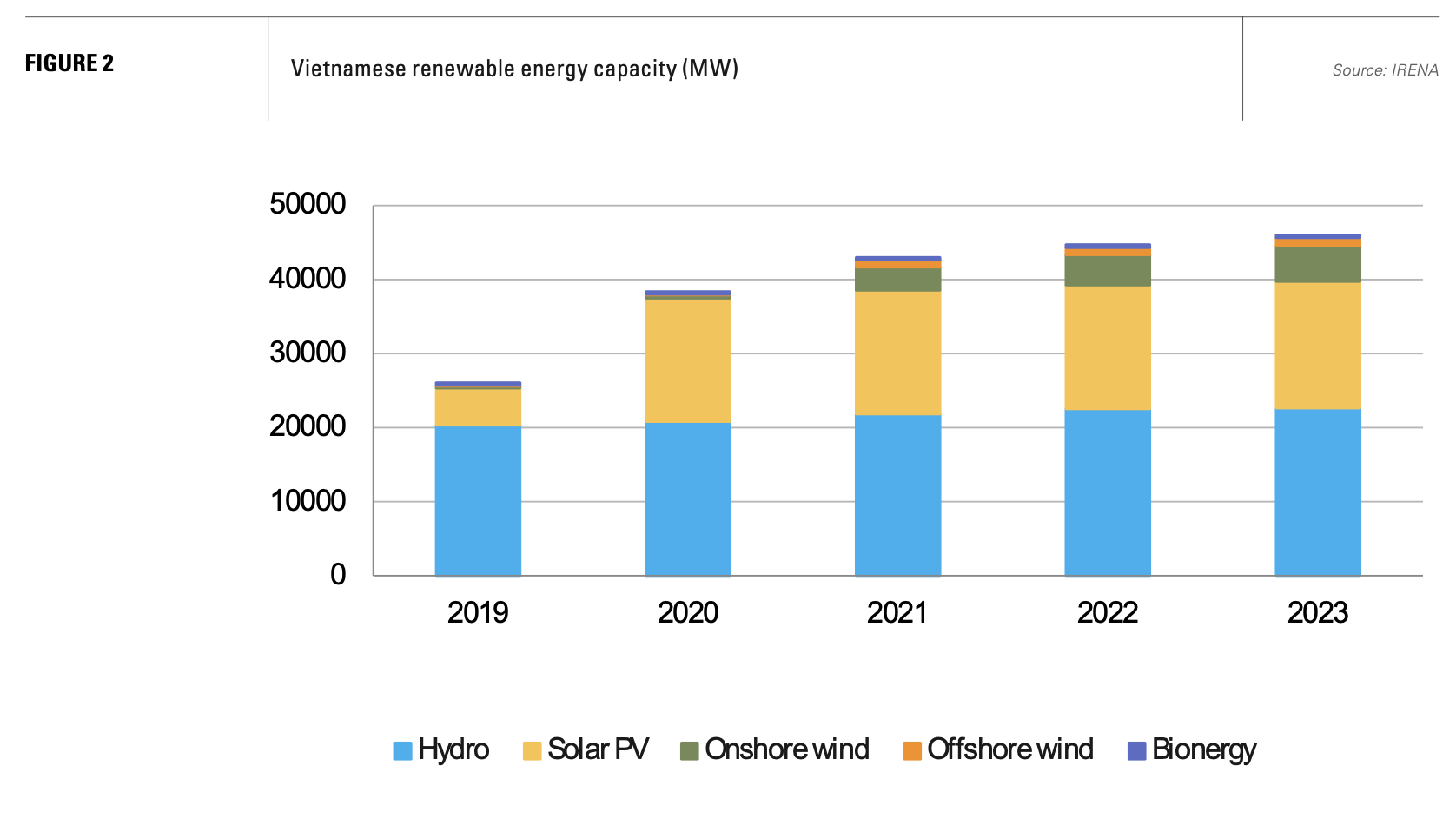

The country will instead focus on renewables and gas-fired power. PDP envisages 21 GW of on and near-shore wind power and 7 GW of offshore wind by 2030. Wind capacity at the end of 2023 stood at 5,888 MW, of which just over 1 GW was offshore (see figure 2). Vietnam has a strong wind resource both on and offshore and the number of offshore wind projects proposed far exceeds the capacity target in PDP8. A majority of these projects are joint owned between international partners and Vietnamese companies.

However, there are challenges. A key one is the lack of grid infrastructure to accommodate a large amount of offshore wind, which is planned predominantly in the country’s south. The World Bank estimates the grid investments needed to integrate more renewables at about $35bn, which is beyond the immediate means of state electricity company Vietnam Electricity. The lack of a fully developed legal and regulatory framework for offshore wind is another limiting factor, as is an often opaque and frustratingly complex bureaucracy.

Grid constraints have already set back renewables; it is not just a question of integrating offshore wind. The country saw a renewables boom in 2020, when solar PV capacity leapt from 5 GW to 16.7 GW and wind capacity jumped a year later from 518 MW to 4,118 MW. That boom resulted in significant generation curtailment owing to grid weaknesses, exposing investors to financial losses.

The rate of expansion subsequently fell and new wind and solar additions since then have been modest. Grid weaknesses are likely to persist and prove a drag on renewables’ growth. In particular, solar PV, which is proving the most deployable energy technology elsewhere, is not expected to grow substantially more in the period to 2030, although there is a 10 GW by 2030 target for concentrated solar power.

Hydro generation will continue to see additions, but there is little remaining potential capacity to be used – about 2.7 GW of large hydro and 2.8 GW of small hydro. Low rainfall has also moderated the amount of electricity being generated from hydro, which, in 2019 and 2020, was substantially lower than in 2017 or 2018. Drought conditions last year saw hydro’s share of generation fall to 28.4% from a more normal level around 35%, resulting in much higher coal burn.

Betting on domestic gas

Reduced coal use, fast-rising power demand and breaks on the expansion of renewable energy mean gas will play an increasing role in the country’s energy mix. A key question is how much will be imported and how much will come from domestic resources.

Under PDP8 gas-fired generation capacity will rise from 7.4 GW at the end of 2022 to 13.5 GW in 2025 and to 28-33 GW in 2030, increasing its share of the energy mix (see figure 3). PDP8 envisages 8mn t/yr of LNG imports from 2024 to 2030 on average and up to 15mn mt/yr post-2030 for power generation purposes.

A presentation by the Ministry of Industry and Trade in March suggested LNG imports of 11.4-13.2mn mt in 2030 based on a low and high case, rising to 18.4-19.2mn t/yr in the period 2035-2040. The ministry envisages supplying gas for 22.4 GW of LNG-to-power projects by 2030.

These figures reflect a renewed emphasis on developing the country’s domestic gas reserves. Vietnamese gas production has fallen from over 10.3bn m3 in 2015 to below 8.0bn m3 last year. The government hopes to rejuvenate domestic production to limit its need for LNG. However, there are considerable uncertainties over Vietnam’s ability to sustain and/or boost gas production.

Reflecting the uncertainties, there is a wide range in government forecasts for gas production of 5.5-15bn m3 by 2030, with a target of 10-15bn m3 by 2050.

Increased domestic gas production is predicated on two major projects, Block B-O Mon and Ca Voi Xanh. The former is expected to cost nearly $12bn and target gas in three offshore blocks in the Malay-Tho Chu Basin for power generation. PetroVietnam has a controlling share in the project, development of which has been subject to years of delay. However, PetroVietnam and its partners started the project in October last year. The engineering, procurement and construction contract was awarded to McDermott. First gas is expected in 2026 with peak production reaching 6.4bn m3.

Ca Voi Xanh is larger with expected peak production of 7-9bn m3. However, there is, as yet, no timeframe for a final investment decision. Field development is expected to require significant mitigation efforts for emissions, owing to a high level of CO2 in the produced gas. Field developer ExxonMobil is also thought to have been looking to divest the asset for some time.

In addition, China opposes further Vietnamese oil and gas development in the South China Sea, owing to overlapping maritime boundary claims, a consideration which has held up Vietnamese offshore oil and gas developments in the past. Ca Voi Xanh lies close to China’s ‘nine-dash line’. As a result, while the prospects for Block B-O Mon development have improved, considerable uncertainty surrounds Ca Voi Xanh and other projects in the South China Sea.

A failure to meet domestic gas production targets and a renewables expansion stymied by the issue of grid investment could therefore result in a greater need for LNG imports than currently envisaged.