Why Ukraine Has to Reform its Gas Sector

In April 2015, the Ukrainian parliament passed a long-awaited law on the gas sector which paves the way for the extremely difficult process of reforming and de-monopolising the Ukrainian gas sector. The law will come into force on 1 October 2015 and involves the break-up of the state-owned company Naftogaz, the current monopolist, and the gradual creation of a competitive gas market in line with the so-called Third Energy Package. At the same time, a threefold increase in the price of gas paid by individual customers and the public sector was introduced. The price had been subsidised for years and no previous government had ever decided to raise it.

The comprehensive reform of the gas sector is one of the most important and most difficult reforms Ukraine has to implement. Its success will be of fundamental importance for the Ukrainian state due to its impact on several major areas of the state’s functioning. Without the marketisation of gas prices and an improvement in Naftogaz’s financial standing (in 2014, the company’s deficit accounted for 7% of Ukraine’s GDP), it will be impossible to reform Ukraine’s public finances to end the long-lasting economic crisis. Without an improvement in Ukraine’s energy efficiency, which currently is one of the world’s lowest, it will be impossible to reduce the country’s dependence on the import of gas. Successful implementation of the reform will also be important in the context of the future of Ukrainian-Russian relations. The question of gas supplies has been one of the major aspects of this relationship since 1991. Another extremely important consequence of the reform will be to eliminate the main source of income from corruption in Ukraine., which has benefited the ruling elite since the 1990s. Corruption seems to be the reason behind the reluctance of all previous governments in Kyiv to reform the gas sector.

Ultimately, successful implementation of the reform will be a milestone for Ukraine in its attempt to leave the post-Soviet paradigm of how the state, its political elites, its economy and society function. However, the significant changes implemented so far in the gas sector have been insufficient, and require the adoption of several other laws and introduction of further price increases. It remains an open question whether the Ukrainian government will have sufficient determination and political will to complete the reform which has just been launched.

A gas-dependent state

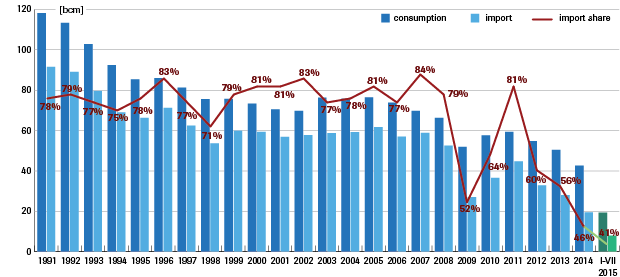

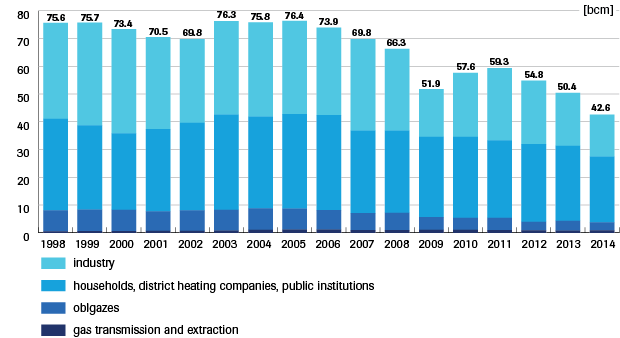

Gas accounts for around 35% of Ukraine’s energy balance. However, due to its economic and political significance, the gas sector has been one of the most important dimensions of the Ukrainian state’s functioning for over two decades now. In the peak years of 2000–2006, the level of annual gas consumption was 70–75 bcm, including around 20 bcm from domestic extraction[1]. The volume of Ukraine’s gas imports (mainly from Russia) placed it among the world’s five largest gas importing countries, and made it the largest single recipient of gas from Russia. Due to a gradual increase in the price of Russian gas, and also the economic crisis, Ukraine’s gas consumption fell from 59.3 bcm in 2011 to 50.4 bcm in 2013 and 42.6 bcm in 2014 (see Appendix: chart 1). The paradox of the situation was that despite Ukraine being a large gas consumer, the price of gas on its domestic market was one of Europe’s lowest.

Ukraine’s great demand for gas, which is disproportionate to the size of its economy, results from the fact that this country has one of the world’s lowest energy efficiency ratios[2]. In Ukraine, the amount of energy needed to generate one unit of GDP is three times larger than the average amount calculated for OECD countries[3]. The Ukrainian industrial sector’s energy efficiency level stands at 51% of the EU’s average level; in the case of the service sector it is 46%, of the construction sector 11.3%, and of the housing sector 61.9%. Such low values are due to several major factors, including outdated heating technology, a backward industry sector and the lack of thermal insulation on residential buildings. This means that Ukraine has a great and still unused potential for energy savings, which in 2011 was estimated at 26 million tonnes of oil equivalent, corresponding to 29.3 bcm of gas[4]. Almost a quarter of these potential savings could be achieved in metallurgy, which was a traditional foundation of Ukrainian industry and the main source of the country’s exports.

In recent years, Ukraine has seen only a small improvement in its implementation of energy-saving technologies. The level of energy efficiency in the industrial sector grew by around 1.5% a year, whereas the figures for the housing sector experienced a gradual decline of 0.2%[5]. The latter value was mainly caused by the subsidy of gas prices, which offered no encouragement to users to save energy. According to Naftogaz’s CEO Andriy Kobolev, if investments worth US$10 bn were made, within 3–5 years it would be possible to save 5–6 bcm of gas annually, a volume accounting for a quarter of gas imports in 2014[6]. This calculation mainly applies to the heat and power generation sector and to private households.

Gas-related corruption income

Since the creation of the independent Ukrainian state, the gas trade has been the main source of corrupt profits for the ruling elite. This concerned both the import of gas from Russia and the non-transparent trade in domestically extracted gas. The key role in these mechanisms was played by companies which served as intermediaries in the supply of gas from Russia; these companies had ties to the governments of both countries[7]. The total lack of transparency in Naftogaz was equally important. Naftogaz, Ukraine’s largest enterprise, fell prey to all the subsequent governments, which in this way gained control over the revenues from the domestic gas trade. Corrupt gas schemes boomed during Leonid Kuchma’s presidency (1994–2005), became consolidated during Viktor Yushchenko’s rule (2005–2010)[8] and continued under Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014). Understanding the mechanism of the dependence of post-Soviet Ukraine’s elites on corruption income generated by the gas sector is one of the prerequisites for understanding how the Ukrainian state functioned after 1991 and why it is currently undergoing a systemic crisis[9].

None of the governments of post-independence Ukraine has been interested in changing the system which had a damaging effect on the state, but at the same time brought massive illegal profits to individuals in power. As a consequence, Kyiv became unable to devise an efficient energy policy or implement reforms (including adopting legislative solutions in the gas sector[10] promoted by the EU, and boosting the country’s energy efficiency). This has further magnified the scale of the problems. Systemic corruption has become the main feature of the Ukrainian gas sector, thereby contributing to a further weakening of the state.

Moscow also used gas-based schemes to corrupt the Ukrainian elite, which aggravated Ukraine’s dependence on Russia. A key moment in this process was January 2009, when the then Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko signed an extremely unfavourable gas contract with Russia[11]. Its main consequence involved a rise in the price of Russian gas to a level which turned out to be one of the highest paid by Gazprom’s foreign clients. This contributed to a further decline in Ukrainian public finances (more on this later in the text). The unreformed energy sector, in particular Naftogaz’s rapidly rising deficit, had a negative impact on other sectors of the economy, and became one of the causes of the drop in Ukraine’s GDP which has been observed since mid-2012. The elimination (or at least the considerable reduction) of the income from corruption obtained from the gas sector is therefore a precondition of the complex reform of the Ukrainian economy and of an improvement of political standards.

Naftogaz – an account in the red

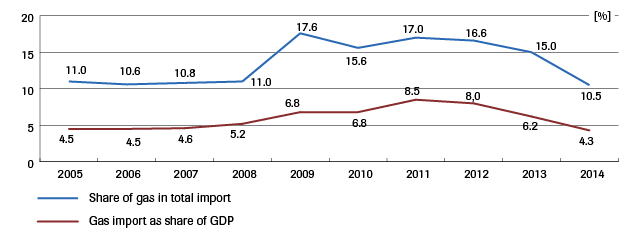

Endemic corruption, combined with the rising prices of Russian gas[12] and the subsidies of the prices paid by individual customers[13], further aggravated the state of Naftogaz’s finances. In Ukraine, recipients of gas can be separated into two categories: (1) clients who pay a regulated (subsidised) price for gas: individual customers, the public sector, and heat and power conglomerates; and (2) the industrial sector and the business sector which pay market prices. The share of the first category of clients is around 55% of total gas consumption (see Appendix: chart 2). Simultaneously with the price of gas for a large portion of customers being held at an artificially low level, there was a gradual rise in the cost of gas purchased from Gazprom. In 2005–2007, the annual purchase of Russian gas accounted for around 4.5% of GDP, whereas in 2011–2012 this increased to 8.5% of GDP (see Appendix: chart 3).

The high price of Russian gas drove up Naftogaz’s debt. The company financed its operations by issuing bonds which were then bought by the state. This led to the de facto shifting of the company’s massive debt onto the Ukrainian state budget, which in turn contributed to a gradual aggravation of the condition of Ukrainian public finances, and of its macroeconomic stability, including the country’s current account (the share of gas in Ukraine’s total imports increased to 17%). This was also one of the main reasons for the increase in the budget deficit from 2% of GDP in 2008 to 7–9% in 2009–2010[14]. In 2014, Naftogaz’s deficit was 110 bn hryvnias (around US$9 bn). This sum was covered from the Central Bank’s currency reserves[15]. This means that the company’s deficit accounted for 7% of Ukraine’s GDP[16]. Without the help granted by the state, Naftogaz would have gone bankrupt long ago.

Naftogaz’s debt has mainly been caused by the fact that the supply of gas to individual customers and to public sector bodies was subsidised, and by the fact that some industrial conglomerates, in particular from the chemical sector, as well as power plants failed to pay the amounts they owed for their gas supplies. The size of the deficit is all the more striking when comparing the company’s debt, which was covered in 2014 by the state (US$9 bn), with the total cost of gas imports from Russia and the West (US$5.7 bn).

A plan to reform Naftogaz

The company’s disastrous state means that any reform of Ukraine’s public finances (and its economy more generally) would be virtually impossible without reforming Naftogaz. This is why in recent years[17], restructuring Naftogaz and marketising the gas prices for individual customers have remained top priority issues in all the IMF’s aid programmes for Ukraine. Successive governments of Ukraine have opposed the plans to increase the price of gas for individual customers because regulated gas rates had formed the basis of the state’s social policy for years. The lack of political will within the Yanukovych administration to marketise gas rates was the reason for the suspension of the IMF programme worth US$15.5 bn agreed in June 2010. Despite Kyiv’s attempts to resume dialogue with the IMF, no compromise had been reached by the end of Yanukovych’s rule due to the lack of agreement on the issue[18].

The IMF’s programme worth US$17.5 bn, which has been in force since February 2015, sees restructuring Naftogaz as its priority goal. This would involve reducing the company’s deficit to 3.1% of GDP in 2015, to 0.2% of GDP in 2016, and making the company profitable in 2017. Another condition determining Ukraine’s chances for receiving another loan involved raising the price of gas for private households by 231%–326%, depending on the group of recipients, and a 67% increase in the price of heating. However, even as drastic an increase as this would not guarantee a full marketisation of the price of gas and heating. This is why the IMF’s programmes provide for another two increases to be introduced in April 2016 and April 2017. To alleviate the impact of the growing prices on society, the government has introduced subsidies worth 24 bn hryvnias (around US$1.2 bn) for the poorest customers. Moreover, Kyiv and the IMF expect that the price increase and the requirement to install gas meters in households will contribute to a reduction in the level of gas consumption[19].

The increase in the price of gas for individual customers has been criticised by some of the coalition parties (Batkivshchyna, the Radical Party) and by the media, which claim that much cheaper domestically extracted gas could be used to cover the demand of individual customers[20]. The IMF and several experts have put forward reasonable arguments suggesting that holding the price of gas for individual customers at a level several times lower than the market price has been one of the main causes of corruption in the energy sector.

Aside from the rise in the price of gas for individual customers and for the public sector, intensified activities aimed at collecting the amounts due for the supply of gas to customers have been planned with the aim of improving Naftogaz’s financial standing. According to estimates, as of mid-August 2015 the value of customers’ liabilities towards the company was nearly US$1 bn, 70% of which are liabilities generated by heat and power plants[21].

The successful diversification of gas imports, achieved by launching reverse gas supplies from the West, in particular via Slovakia, has contributed to an improvement in Naftogaz’s financial condition. This has become an important argument in Kyiv’s talks with Gazprom over a possible reduction in the price of Russian gas. The expected expansion of the capacity of pipelines running via Slovakia to the current 14.5 bcm per year, combined with the technical maximum capacity of the interconnections with Hungary and Poland (6.1 bcm and 1.5 bcm respectively) would make it possible for Ukraine – for the first time in its independent history – to abandon the need to purchase Russian gas. Aside from the law on the gas market, this has been the greatest success of Ukrainian energy policy since the end of the ‘Euromaidan’. In the first half of 2015, Naftogaz imported 6.1 bcm of gas from the EU and 3.7 bcm from Russia (62% and 38% respectively)[22].

A breakthrough gas market law

The reform of the energy sector has become one of the major goals announced by the post-Euromaidan government. In March 2014, there was a change in Naftogaz’s leadership, and Andriy Kobolev, then aged 35, was appointed the company’s CEO. In July 2014, the parliament amended the law to allow Western investors to take part in modernising the Ukrainian system of gas transit pipelines. However, specific reform-related actions aimed at changing the status quo in the gas sector lasted several months. On 9 April 2015, the Ukrainian parliament passed a gas market law[23], which is one of the most significant reforms adopted by the new government so far. The parliament’s vote in favour of the new law (290 votes in favour were cast), which had been written in close cooperation with the Energy Community Secretariat, was in fact forced upon it by the IMF, which saw it as a precondition of granting Ukraine another aid package worth US$17.5 bn.

The main purpose of the law is to implement legal acts in Ukrainian legislation which regulate the EU gas sector (including the Third Energy Package). This, in turn, is intended to create a competitive gas market in Ukraine in all segments of the market. The law sets legal and organisational rules for how the gas market should function, provides for gas market de-monopolisation, offers consumer protection and enables consumers to freely choose their gas supplier.

The newly-adopted law reveal the need to break up Naftogaz, which currently combines the function of gas producer with the tasks of transporting, storing and distributing gas. Gas pipelines and underground storage tanks will be separated into independent companies controlled by the state, with access to them guaranteed to all market participants. It will also be necessary to form subsidiaries of Naftogaz which will be entrusted with the extraction and distribution of gas. As a consequence, several separate gas network operators and gas distribution and storage companies will emerge which will operate on the basis of certificates issued by an independent regulatory office. Operators will be obliged to provide all market participants with access to the gas transmission network.

The new gas law is intended to deprive Naftogaz of its current status as a monopolist and to foster competition on the gas market. It is also expected to stimulate the investment activity which is necessary to modernise the gas sector. The law will also strike at the interests of some oligarchs who control around 70% of the regional companies which distribute and sell gas (the so-called oblgazes)[24], because it obligates these companies to pay for access to gas networks (previously, such access was free of charge). At the same time, the law fails to answer the question as to what should be done with the mostly privately-owned oblgazes which manage regional gas networks (which are state-owned entities) and at the same time sell gas to end users, which is against the newly-adopted rules requiring the transport and distribution tasks to be separated[25].

The law will come into force on 1 October 2015 (and some of its provisions will come into force several months later), but a number of issues related to the new shape of the gas market will have to be regulated in several other laws. The current law also fails to answer a number of important questions, such as the role of Naftogaz after the market becomes de-monopolised, or the planned date of the company’s split into several operators. It should be assumed that it will take a long time to adopt further laws, and new entities can be expected to enter the market once these new laws are adopted. Currently, work is under way on submitting a draft law to parliament on creating an independent energy market regulator to replace the current National Committee for State Regulation of Energy and Utilities (NKREKP)[26]. According to the draft law, NKREKP is to be replaced with a new, fully independent regulator with a considerably broader scope of competence, which would enable it to carry out investigative activities, initiatives aimed at protecting market competition, and impose fines. The law is expected to be in full compliance with the EU’s Directive 2009/72/EC, a part of the Third Energy Package.

Following the adoption of the gas market law, the Ukrainian parliament passed another two laws intended to improve standards in the gas sector. The IMF made the granting of another loan instalment conditional on Ukraine adopting these two laws. On 14 May 2015, the parliament passed a law stabilising the financial standing of Naftogaz. The law expands the scope of legal solutions available to the company to collect its outstanding debts, including from public utility units, heat and power plants and industrial facilities. On 16 June 2015, a law on increasing transparency in the energy sector was passed which obligates extraction companies to publish their financial statements and reports on their business activity. The new law targets mainly state-owned companies such as Ukrnafta and Ukrgazvydobuvanya, and its aim is to introduce the requirement to maintain transparency and to boost the attractiveness of the mining sector in the eyes of investors.

Prospects for gas market reform

The gas sector reforms carried out so far by Ukraine’s post-Revolution government can be viewed as ambivalent. On the one hand, an extremely important law on the gas market has been passed and gas prices for individual customers have seen an increase of around three-fold. On the other hand, it should be noted that the government launched its first real reforms as late as a year after the events of the Euromaidan. Moreover, the adoption of reforms has been de facto forced upon Ukraine by the IMF, which made granting of a rescue loan (without which Ukraine would have defaulted) conditional upon implementing these reforms. It should also be emphasised that the gas market law adopted in April 2015 is not the end, but just the beginning of reforms of the Ukrainian gas market. On its own, this single, albeit very important legal act will not trigger radical changes in the gas sector; it will have to be supplemented by further laws. Preparing a full set of standards and legal solutions to form the foundations of the new gas market is likely to take several months, if not years. For the time being, Naftogaz has maintained its monopoly in all domestic market segments and the status of the sole importer of gas[27]. The organisational details and the schedule of the planned break-up of the monopolist remain unknown.

Increasing the price of gas for individual customers and for the public sector by around 300% does not mean the end of the marketisation of gas prices. However, this has been an admittedly bold move which all previous governments failed to make, and which the government headed by Arseniy Yatsenyuk had also tried to postpone. The memorandum signed with the IMF provides for another two price increases (the last one is to be introduced in April 2017), which is intended to end the years-long process of subsidising gas prices. At the same time, the decision involving such a drastic price increase will impact consumers starting from the upcoming autumn heating season, and will likely trigger social discontent. The price increase is particularly important in the context of the pauperisation of society caused by the ongoing economic crisis. The government’s decision to introduce the price increase has been criticised not only by the opposition but also by some of the coalition parties.

It remains an open question whether the current government will have the necessary political will to continue gas sector reforms. For this to be possible, further laws will need to be prepared and voted on by the Ukrainian parliament. Furthermore, it should be expected that some of the beneficiaries of the old system will oppose the reform, fearing that it might undermine their major interests, and will attempt to block it. Without a consistent and full implementation of the gas sector reform, which should include increasing the energy efficiency of the economy and of the public sector, it will be impossible to improve the condition of Ukraine’s public finances, reduce its budget deficit, improve its current account, reduce income from corruption and improve standards in Ukrainian politics. In this context, the gas sector reform can be considered ‘the mother of all reforms’, and its successful implementation will determine the chances for success of the entire process of transformation currently under way in Ukraine.

Figure 2

Figure 3

[1] In the early 1990s, Ukraine consumed over 100 bcm of gas per year, but in subsequent years the level of consumption fell to approximately 75–85 bcm.

[2] According to the Enerdata Global Energy Statistical Yearbook 2015, to produce one unit of GDP Ukraine needs 0.320 kilogram of oil equivalent. Worse ratios were recorded only for Russia (0.340) and Uzbekistan. For comparison, Poland’s is 0.129, Germany’s 0.106.

[3] Taking account of the purchasing power parity. Data after: Ukraine 2012, International Energy Agency, OECD/IEA 2012.

[5] For comparison, in 1996–2010 the ratio of energy efficiency recorded for Poland increased by 42%, including the ratio recorded for households, which increased by 34%. http://www.odyssee-mure.eu/publications/profiles/poland-efficiency-trends-polish-version.pdf

[6] An interview with Andriy Kobolev: АндрейКоболев: "Безрыночнойценырынкагазанебудет!", zn.ua, 5 June 2015.

[7] Mainly Itera (1995–2002), EuralTransGas (2002–2005) and RosUkrEnergo (2006–2009).

[8] See e.g. It’s a Gas—Funny Business in the Turkmen-UkraineGas Trade, Global Witness 2006.

[9] This model has been described in detail by Margarita Balmaceda. See M. Balmaceda, Energy dependency, politics and corruption in the former Soviet Union, London-New York 2009 and The politics of energy dependency. Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania between domestic oligarchs and Russian pressure, Toronto 2013.

[10] This requirement is a result of Ukraine’s membership of the Energy Community.

[11] Until now, it is not clear why Yulia Tymoshenko, an individual with extensive experience in the gas sector, decided to sign this unfavourable agreement. What is certain is that one of her motives was to eliminate the RosUkrEnergo (RUE) company from the gas market. The company was co-owned by the oligarch Dmytro Firtash, who at that time was in conflict with Tymoshenko. In the context of the upcoming presidential elections, Tymoshenko intended to deprive Firtash of his revenues from the trade in gas, which could have been used against her in the pre-election campaign.

[12] The price of 1000 m3 of gas purchased from Gazprom rose from US$180 in 2008 to US$259 in 2009 and to US$427 in 2012. In 2012, the average price of gas paid by Gazprom’s clients in the EU was US$385.

[13] The price of gas on the domestic market paid by individual customers and the public sector was approximately 4–5 times lower than the price paid to Gazprom.

[14] Ukraine 2012, a report by the International Energy Association, OECD/IEA 2012.

[15] Naftogaz’s debt was 1.5 times higher than Ukraine’s entire budget deficit;http://censor.net.ua/n338512

[16] In 2014, Ukraine’s GDP was 1566 billion hryvnias (approximately US$132 billion).

[17] In 2008, 2010, 2014 and 2015 respectively.

[18] The failure of the IMF’s aid programme resulted in Kyiv receiving a loan from Russia worth US$15 billion in December 2013 (although Ukraine actually received only the first instalment of the loan worth US$3 billion). The funds were intended to stabilise the economic situation ahead of the presidential elections planned for the beginning of 2015.

[19] As at the end of May 2015, gas meters have been installed in 71% of households (only 16% in Kyiv). В Україні встановлено десятимільйонний лічильник газу, 28 July 2015.

[20] In 2014, the state-owned companies Ukrgazdobycha and Ukrnafta extracted 15.1 bcm and 1.7 bcm of gas respectively, whereas the volume extracted by private gas extraction companies was 3.3 bcm. An additional 0.3 bcm of gas was extracted by Chernomorneftegaz on the Crimean Shelf, over which Ukraine lost control after the annexation of Crimea by Russia. In August 2014, levies imposed on oil and gas extraction companies increased twofold. This resulted in a 5.7% decrease in gas extraction in January–July 2015. In July 2015, a draft law providing for a reduction in the levies for companies operating in the gas sector was registered with the Ukrainian parliament.

[21]Заборгованість під приємств-боржникі вперед НАК «Нафтогаз України»,Naftogaz, 20 August 2015.

[22] Нафтогаз оприлюднив статистику цін імпортованого газу за другий квартал 2015 року, Naftohaz, 17.08.2015.

[24] Mainly Dmytro Firtash, who owns controlling packages in 21 oblgazes and minority packages of a further 10; and Rinat Akhmetov, who controls the Kyiv-based company Kyivenergo, among others. http://gazeta.zn.ua/energy_market/s-kazhdoy-konforki-_.html

[25] Andriy Kobolev stressed this in one of his interviews. Андрей Коболев: Европейцы ждали, когда мы заговорим о посреднике, Ukrainska Pravda, 29 May 2015.

[26] NKREKP was created in September 2014 by a decree by President Petro Poroshenko, and is supervised by the President. It was intended to replace the National Committee for State Regulation of Energy (NKRE), a quasi-regulator which had existed since 1995. Provisions concerning NKREKP were also included in the gas market law.

[27] In November 2014, the Ukrainian government restored Naftogaz’s monopoly on the import of gas, which had been lifted in 2012. The decision was criticised by the Energy Community. Despite the fact that the government’s decree remained in force until 28 February 2015, Naftogaz carried out 99% of gas imports until early July 2015. This was because it had booked almost the entire volume of gas available in pipelines which receive gas from the EU. Коболев: «Нафтогаз» предложил частным компаниям импортировать газ в Украину, Business.ua, 10 July 2015.

_f268x104_1368211563.jpg)