Wintershall Dea – ‘champion’ idea [NGW Magazine]

The birth of Wintershall Dea at the start of this month marked completion of the largest upstream oil and gas merger in Europe for more than a decade. And while the announcement spoke of “a global portfolio with strong growth prospects”, it is telling that CEO Mario Mehren – who held that position at Wintershall – described the new entity as “a European champion”.

For while both Wintershall and DEA regarded themselves as international companies – because of their substantial interests outside Europe, in Latin America, North Africa and the Middle East – the combined Wintershall Dea remains primarily a European company.

Its headquarters is in Germany; the largest portion of its hydrocarbons production – heavily weighted towards gas – is in Russia; and the second-largest portion is in the North Sea. It is within this arena that the company will face its most immediate challenges and its greatest opportunity.

So far, so good

Wintershall and DEA agreed in principle to merge back in September 2017 and a definitive agreement was signed a year later by their respective owners – the German chemicals company BASF, and LetterOne, the Luxembourg-based investment fund co-founded in 2013 by Mikhail Fridman, the Russian oligarch.

Onwards from that point, the complex process of securing the numerous regulatory and other approvals needed for the merger to proceed seems to have gone remarkably smoothly. Fridman’s involvement in LetterOne was enough for the UK government to force it to sell its stake in some UK gas fields.

Closing conditions included approvals from merger control authorities and clearance under foreign investment regulations. Within Germany, approvals were needed from several mining authorities and, because of Wintershall’s gas pipeline interests, the German federal network agency, BundesNetzAgentur. Despite all this, the deadline of completing the transaction in the first half of 2019 was comfortably met.

Fears that Wintershall’s ownership of a sizeable gas transportation business within Germany might raise concerns over a partly Russian-owned entity owning European assets proved to be groundless.

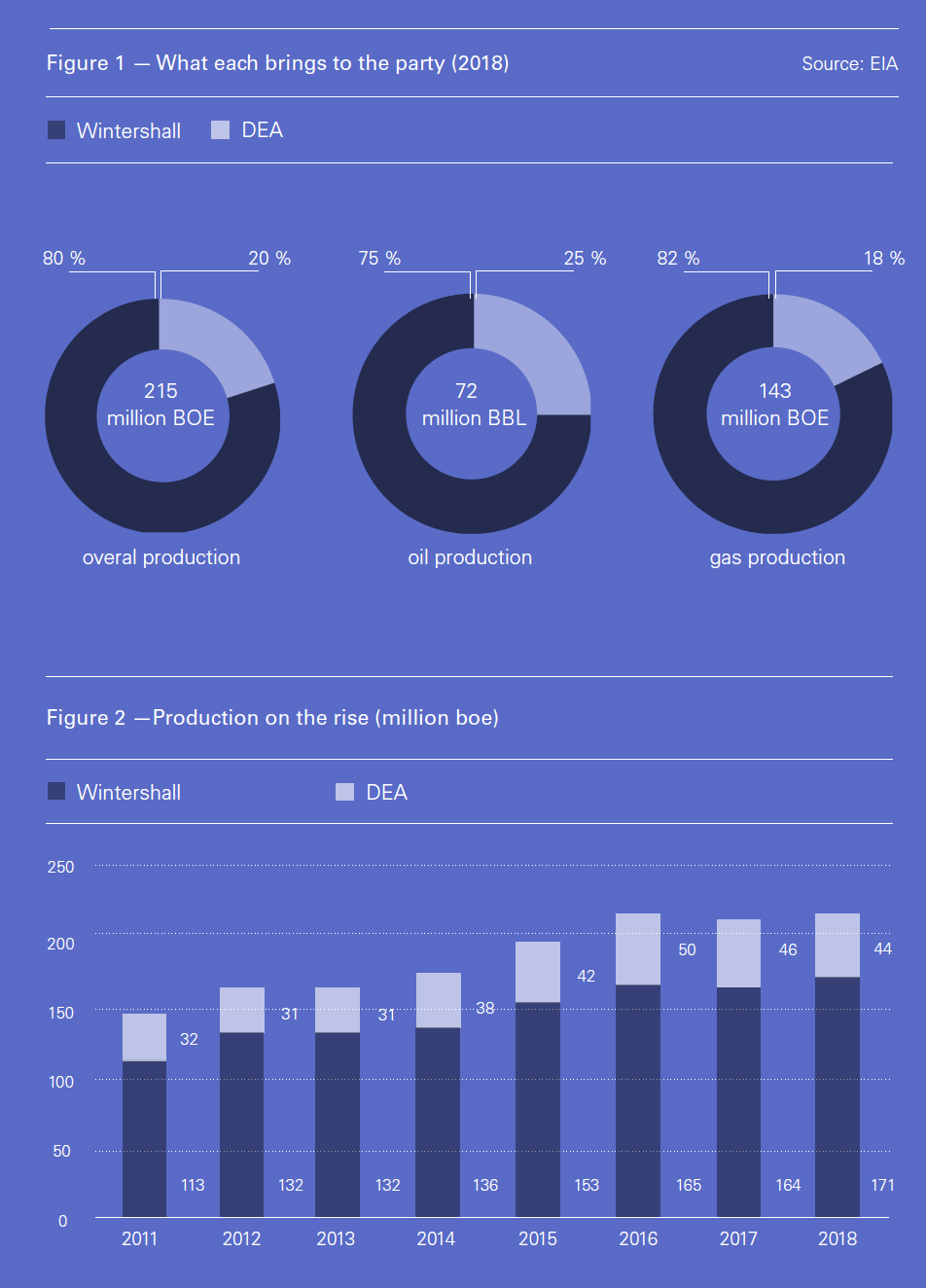

The ease with which approvals were obtained is partly explained by the fact that Wintershall Dea was not a merger of equals, as the charts below make clear. Wintershall’s 2018 hydrocarbons production of 171mn barrels of oil equivalent (boe) was almost four times that of DEA, at 44mn boe, while its sales were two-and-a-half times those of DEA (see table).

The disparity in the size of the two companies was reflected in the merger agreement. Initially, LetterOne owns one-third of Wintershall Dea, while BASF owns the remainder – “reflecting the value of the respective exploration and production businesses”.

Because Wintershall has, through its Gazprom joint venture Wiga, stakes in a sizeable but independently operated gas transportation business – Gascade, Opal and NEL– BASF has also received additional preference shares. These will eventually be converted into ordinary shares of Wintershall Dea, giving BASF a total shareholding of 72.7%.

Integration of the two companies is expected to take around a year and – subject to market conditions – BASF and LetterOne expect to offer shares in Wintershall Dea though an initial public offering (IPO) in the second half of next year.

Helping to pave the way for that IPO is an agreement reached earlier this year with an international banking consortium, including five US banks, for €6bn ($6.6bn) of finance for Wintershall Dea to pay off shareholder loans. “This,” says Mehren, “will relieve us of our obligations to shareholders and gives us a good financial basis for our future growth.”

“Scale and clout”

Despite the disparity in the size of the constituent companies, Mehren insists the newly created company is the “ideal size” to meet current market challenges.

“We are large enough to be a relevant partner for the state-owned oil and gas companies,” he says, “and at the same time independent and flexible enough for complex tasks where we apply our engineering skills. Now is the right time for Wintershall and DEA to join forces so that the new company has the scale and clout to compete in today’s environment.”

What has emerged from the merger is a company whose constituents together produced 215mn boe in 2018, equivalent to 590,000 boe/d. Of this, 67% was natural gas and 33% oil.

Their combined production has grown strongly over the past eight years, as the chart below shows, and the expectation is that it will continue to so do at 6-8%/year – “from both the existing portfolio and new production regions”. If realised, this would put Wintershall Dea on track to reach daily production of 750,000-800,000 boe/d at some point between 2021 and 2023.

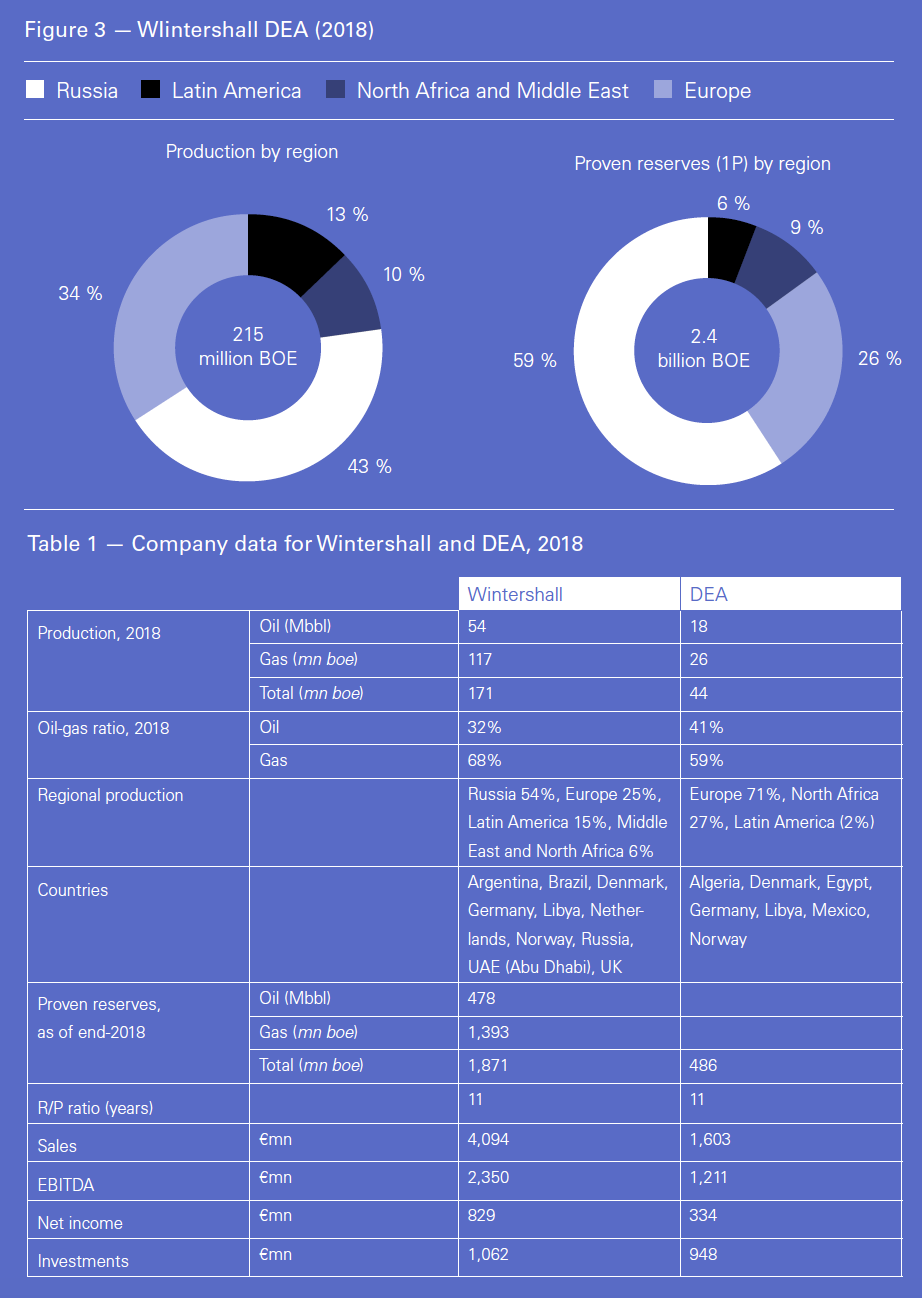

Proved reserves as of the end of 2018 totalled 2.36bn boe, giving a reserves/production ratio of “a healthy 11 years”, says the company; three-fifths of these are in Russia. Combined sales in 2018 were €5.697bn, with combined earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of €3.561bn.

Why merge?

Part of the rationale for the merger was the expectation of synergies of at least €200mn/year, as of the third year following the closing of the transaction. The combined workforce of around 4,200 full-time positions is to be reduced by a quarter and the company says “the social partners are currently working on socially compatible solutions regarding the necessary personnel adjustments”.

Also important, however, is Mehren’s assertion that “the Wintershall and DEA portfolios complement each other perfectly”. The chart below shows the global footprint of the merged company, with 43% of 2018’s production coming from Russia, 34% from Europe, 13% from Latin America and 10% from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). In total, Wintershall Dea is active in 13 countries.

Within Europe, Wintershall’s upstream positions in Germany and the North Sea (Norway, the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark) are complemented by DEA’s positions in Germany, Denmark and Norway. Within Middle East/North Africa, DEA adds interests in Algeria, Libya and Egypt to those held by Wintershall in Libya and Abu Dhabi – though the political and security situation in Libya will remain troublesome for the foreseeable future. Within Latin America, Wintershall’s activities in Argentina and Brazil are complemented by DEA’s activities in Mexico.

The company’s upstream activities are supplemented by investments in gas infrastructure and midstream services. These “non-cyclical midstream businesses generate an important source of stable cash flow,” says the company.

Wintershall is also a shareholder in the 55bn m³/year Nord Stream pipeline that connects Russia directly with Germany across the Baltic Sea and is one of five European companies providing finance for the 100% Gazprom-owned second phase of that pipeline which is now being built.

In the run-up to completion of the merger, Wintershall Dea’s constituent companies had a number of successes in their operations in Latin America, Middle East and North Africa that hold out promise for the future if exploration efforts turn out to be successful. These included:

* The award of a new concession to Wintershall at the end of 2018 for the giant Ghasha sour gas field in Abu Dhabi, thanks in part to the company’s experience in producing sour gas within Germany;

* DEA’s recent entry into Mexico; and

* Exploration bid round successes in Argentina – where Wintershall has been active for over 40 years, including in the Vaca Muerta shale formation – and Brazil, a new region for the company.

Spotlight on Russia

However, the most important region for Wintershall Dea is – and will remain – Russia, says Mehren. In 2018 it accounted for over half of Wintershall’s production and further field developments in western Siberia will make a significant contribution to plans to increase Wintershall Dea’s production.

So, how concerned is Mehren about the poor state of relations between Russia and the US and Europe?

“We have longstanding and trustful business relationships with Russian companies or companies owned by Russian citizens,” he says. “These relationships are not directly affected by any sanctions. Of course, we are monitoring the development closely and constantly.”

Also controversial is Gazprom’s current development of the NS 2 pipeline, the construction timetable of which is threatened by Denmark’s apparent reluctance to grant approval for the section that will pass through its waters.

“Implementation of NS 2 will strengthen infrastructure and security of supply in Europe, which is particularly important given the decline in production there,” says Mehren. “NS 2 is essential for giving European customers, especially industrial customers, access to competitively priced gas.”

German coal-power phase-out

As such, the project will play a crucial role in a big opportunity that Wintershall Dea is hoping to capitalise on – following the recommendation early in 2019, by a special commission, that Germany should phase out coal-fired electricity generation by 2038.

“The coal exit commission gave a very strong recommendation, which is supported by consensus in society,” says Mehren. “This will now be incorporated into legislation by the government. I believe this will happen fairly quickly because Germany has observed over many years that its climate goals haven’t been reached, and that is because of coal-fired power generation.”

He believes that the coal phase-out will boost Germany’s demand for natural gas, and adds that the country has plenty of idle gas-fired generation capacity. The 55bn m³/year of gas that NS 2 could transport is equivalent to 300 TWh of electricity, he says – “enough to replace all of Germany’s coal-fired power without subsidies.”