Bottled-up Gas [NGW Magazine]

The bulk of Central Asia’s gas exports go to either Russia or China. The former has enough gas of its own and takes central Asian supplies only as long as they are very competitive, while the latter uses its many import options, including LNG, as leverage to drive down prices.

Turkmenistan, endowed with 19.5 trillion m3 in proven gas reserves according to BP estimates, has laboured for decades to establish alternative export routes to Asia and Europe, achieving little tangible success as the downstream pipelines westwards are already occupied and the long-mooted Turkmenistan-India pipeline has first to cross Afghanistan. Neighbouring Uzbekistan is pursuing a different strategy, however.

The country, with a smaller but still considerable 1.2 trillion m3 in reserves, has no interest in expanding gas exports. Instead, it wants to use as much gas as it can domestically to produce higher-value products that it can use or export as liquids.

As a significant commitment to this policy, Uzbek prime minister Abdulla Aripov declared in January that the government would seek to bring its exports down to zero within the next five years.

“By 2025, measures will be taken to stop the export of natural gas and expand processing within the country, as well as increase production of value-added products,” local media quoted him saying.

But unless existing agreements with foreign producers are honoured, this could jeopardise investments already committed upstream.

Uzbekistan sold some 5.1bn m3 of gas to China and a further 6.8bn m3 to Russia last year, as well as small volumes to other central Asian states, the Fergana news agency reported in March.

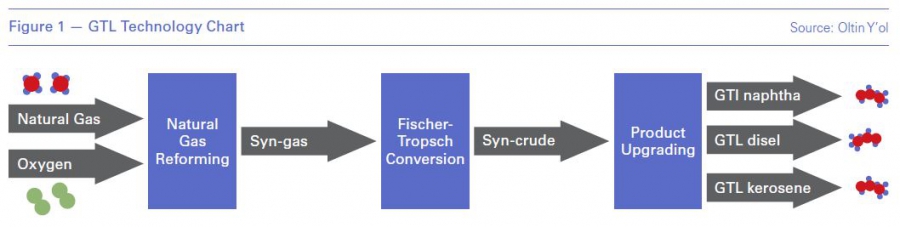

Under these plans, state oil company Uzbekneftegaz (UNG) is investing in two major downstream projects: the Oltin Yo’l gas-to-liquids (GTL) project; and a petrochemical expansion at the adjacent Shurtan gas processing complex. The first and more ambitious of these ventures is due for completion this year.

An alternative solution

Central Asia is seen as an attractive location for GTL technology, which turns gas into synthetic fuels, given the region’s gas wealth and the aforementioned geographical difficulty in commercialising these resources. Turkmenistan commissioned Central Asia’s first GTL plant last year. But Uzbekistan’s $3.6bn project will be twice the size, capable of converting up to 3.6bn m3/yr of gas into 1.5mn mt/yr of kerosene, diesel, naphtha and LPG. All these products are to be consumed domestically.

“The GTL project... will allow Uzbekistan to monetise further its vast gas reserves while reducing the volumes of imports of crude oil and oil products,” the country’s energy ministry told NGW.

Uzbekistan has struggled for years with intermittent fuel shortages, a major drag on its economy. It has three oil refineries, but they require upgrades and operate at a mere fraction of their nameplate capacity. The issue is that Uzbekistan cannot find an economic means of importing enough crude oil, and its domestic output continues to slide. This has left it reliance on imports, mostly from Russia. The GTL plant offers an alternative.

Work on the project began more than a decade ago, with UNG signing a heads of agreement on its development with South Africa’s Sasol, a GTL pioneer; and Malaysia’s Petronas in 2008. The following year they agreed to form an equal-shares joint venture.

The search for financing began in 2013, with Uzbekistan reaching out to export credit agencies (ECAs) from Asia and Europe. The project suffered its first main setback in 2016, when Sasol decided to shed its stake in the venture.

According to Uzbekistan’s energy ministry, the South African firm had wanted to prioritise its US investments, including an ethane cracker at Lake Charles. Oil, gas and other commodity prices were in a slump at the time, which led to a number of investors pulling out of projects in resource-rich central Asia. Owing to the huge up-front costs, GTL needs a large difference between the market price of oil and gas so that conversion to oil substitutes leaves a profit.

Petronas also left the project to focus on its downstream activities in Malaysia, with both partners transferring their shares back to UNG.

Undeterred, Uzbekistan moved forward on its own and held talks with contractors to see about lowering its cost.

“These discussions resulted in significant cost savings of nearly $700mn,” the ministry says.

Additional savings were made by lowering UNG’s costs and reducing financing expenses, by opting for sovereign rather than limited resource financing, according to the ministry.

Talks with financiers finally reached a breakthrough in December 2018, when Uzbekistan secured more than $2.3bn in funding from China Development Bank, South Korean ECAs Kexim and K-Sure and Russian banks Gazprombank and Roseximbank and other lenders.

Markets

Diesel from the GTL plant will be used in Uzbekistan’s agricultural sector, a major generator of foreign currency, as well as its transport and mining industries, according to the ministry. As agricultural production expands, as the government hopes, so too will demand for diesel.

Kerosene, meanwhile, will be supplied to the airline industry. Uzbekistan is looking to establish itself as a key hub for international air travel, harnessing its position between Asia and Europe. A number of investments are lined up, including the construction of a new international airport in Navoi. But for these ambitions to be realised, kerosene shortages will need to be a thing of the past.

Naphtha will be shipped to the Shurtan complex, where a naphtha cracker is being built to produce ethylene and polyethylene – valuable commodities in Uzbekistan’s textile industry.

“Despite the ongoing low fuel demand environment in light of Covid-19, the GTL plant's reported long-term offtake agreements may help cushion the impact of volatility in energy markets,” Rebeka Foley, an analyst at London-based Prism Political Risk Management, told NGW. “Still, a prolonged weak economic climate will continue to put downward pressure on product prices, weighing on profits from certain transactions not covered by long-term contracts or price regulation.”

Upstream aims

For Uzbekistan to make a long-term success of the GTL plant and other downstream projects, it will need to continue investing in gas production growth.

Since the president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, took office in late 2016, the government has set lofty targets for expanding its gas output. But so far forecasts have not been met. Output fell by a further 7.8% year on year in the first quarter, to 13.07bn m3, according to state statistics. The country plans to ramp up supply by 20% over the next decade, from 60bn m3 in 2019.

Uzbekistan has invited international oil companies (IOCs) to partner with UNG at new projects, including newcomers such as BP and established players like Russia’s Lukoil. But few commitments on development have been finalised.

Lukoil, the country’s second biggest producer after UNG, works under production-sharing agreements (PSAs) at its key projects Southwest Gissar and Kandym. PSAs are favoured among IOCs. But Tashkent is now pushing for the use of risk-service agreements (RSAs) instead.

Under RSAs, IOCs do not receive rights to subsoil resources but are instead paid for the services they provide and the oil and gas they produce. Uzbekistan is yet to finalise a legal framework governing these RSAs, however, impeding new investment.

“There is a movement against PSAs throughout central Asia, not only in Uzbekistan,” Prism’s director Kate Mallinson says. “The easier economic reforms in Uzbekistan have already been passed. It is the thornier reforms such as introducing RSAs which could undermine historic PSAs signed with Lukoil and Gazprom and that challenge the status quo of the political economy, that are much tougher to pass via the necessary decision-makers.”

Tashkent has already signalled it wants to adjust its PSA legislation to allow for more gas to go to the domestic market, and there are concerns over how this – and the move to end exports in five years – will affect Lukoil. The company relies on Chinese sales to recoup its substantial investments, and its PSAs give it the right to export.

Uzbekistan will also need to push ahead with plans to modernise its Soviet-era gas network. The grid suffers from technical losses of up to 15% of total supply, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB).