Delfin LNG prospects brighten [Gas in Transition]

The Delfin LNG project, located on the US Gulf Coast in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, is the latest US development to gain momentum as Europe faces up to a future much more dependent on LNG supplies.

In July, project developer Delfin Midstream secured a sales and purchase agreement (SPA) with Swiss trading house Vitol’s US subsidiary for 0.5mn mt/yr LNG from the first phase of the Delfin LNG floating LNG (FLNG) project. The SPA, which has a term of 15 years, is indexed to Henry Hub.

In August, Delfin signed a heads of agreement (HoA) with the UK’s Centrica for the purchase of 1mn mt/yr LNG for 15 years on a free-on-board basis.

In September, the company agreed an HoA for an LNG export partnership with US gas producer Devon Energy. This provides the framework for a long-term tolling agreement covering 1mn mt/yr of capacity from the project’s first vessel, as well as an equity investment by Devon in Delfin.

Devon also has an option to book an additional 1mn mt/yr of liquefaction capacity either in Phase 1 or later phases of the project and for future equity investments in the project. Devon’s rationale for the deal is to diversify its markets beyond domestic US gas demand.

Assuming that the HoAs with Centrica and Devon progress to bankable deals, Delfin will have sufficient firm off-take to proceed with Phase 1. An FID by the end of the year could see the first FLNG vessel in operation by 2026. Three further vessels are planned for a total of about 13mn mt/yr capacity

Low costs promised

Delfin assesses its total capital costs at $500-550/mt capacity for each of its 3.5mn mt/yr FLNG vessels. In 2020, it completed front-end engineering and design (FEED) for the first vessel in cooperation with Samsung Heavy Industries and Black & Veatch.

At the time, it said the FEED process had resulted in expected total capital costs – including FLNG vessel, disconnectable mooring system, pipeline connections, owner’s costs, transit, installation, commissioning and contingencies – of around $550/mt/yr. Financing costs were excluded. It also said it had an “absolute lowest FID threshold of 2.0 to 2.5mt/yr firm offtake.”

Delfin’s low projected costs reflect the benefits of its nearshore FLNG concept. Upstream costs will be low as feedstock gas will be sourced from the US pipeline system.

Delfin’s low projected costs reflect the benefits of its nearshore FLNG concept. Upstream costs will be low as feedstock gas will be sourced from the US pipeline system.

FLNG projects do not have a record of delivering low costs, but a lot has changed since the first vessels were ordered. Moreover, a crucial distinction needs to be made between nearshore and deep water FLNG. Projects like Shell’s Prelude and the soon to be on-stream Coral Sul project off Mozambique for Eni are far more complex beasts than near-shore FLNG vessels of the type envisaged by Delfin.

The latter use pre-processed gas rather than gas sourced directly from an offshore field, meaning equipment such as separators and high-pressure protection systems are not needed, reducing cost.

However, each vessel needs storage and off-loading capabilities, which would be shared between LNG trains on an onshore plant, and raw material costs, notably steel, have risen substantially since Delfin’s FEED assessment in 2020.

Feedstock transportation

Delfin will also make use of existing infrastructure, which will keep costs down. Feedstock gas will be transported to the FLNG vessels via the existing Enbridge Offshore Pipelines System (UTOS), which was originally built in 1978 to bring oil and gas onshore. The pipeline was abandoned in 2011, but bought from Enbridge by Delfin LNG in 2014.

Reinstating the pipeline’s connections, building a compressor station at the landing point and carrying out work to reverse the pipeline’s direction of flow are integral to the project. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted approval for the reuse of UTOS in September 2017, just a few months after Delfin gained export approval from the US Department of Energy to export LNG to countries with which the US does not have a free trade agreement.

The decision to go offshore also avoids land acquisition and results in fewer permitting hurdles. The US Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration and the US Coast Guard approved the offshore part of the project in March 2017. Delays in attracting off-take partners have meant a number of re-applications for extensions of the approvals, the latest of which was made in July.

The disconnectable mooring system allows the FLNG vessels, which have their own propulsion, to move away from bad weather, for example the path of a hurricane – an important consideration on the US Gulf Coast. This also means that the FLNGs are relocatable on a more permanent basis, if necessary, making them flexible assets.

Arranging finance has not been easy

The central elements of the plan remain the same, but the project has evolved over time in the search for finance. Golar LNG was the initial development partner for the FLNG vessels, but dropped out in 2019, when the prospects for a timely FID on the project looked dim. Delfin also had a preliminary agreement with China Gas Holdings for a 15-year agreement to supply 3mn mt/yr of LNG, but this deal fell foul of US-Chinese trade tensions.

The delays in getting the project off the ground have seen Delfin apply four times for extensions to build the offshore section of the project. If the application made in July is successful, it will have until September 28, 2023 to complete the offshore elements of the development.

The Avocet LNG project, also being developed by Delfin, offers the prospect of even more capacity. This envisages use of the Delfin-owned Grand Chenier offshore pipeline, which could feed gas either into an expanded Delfin LNG deep water port, for a total of six FLNG vessels, or the construction of a second deep water port, Avocet, to support two FLNG vessels in addition to Delfin’s four. The fifth and sixth FLNG vessels are expected to have capacity of up to 4mn mt/yr each.

Market timing

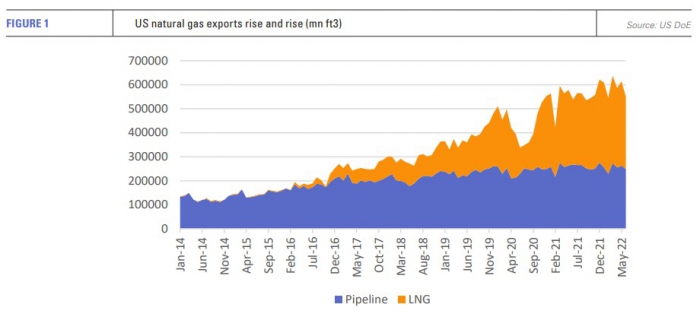

US gas prices have not followed the trajectory expected when the project was first conceived. Continued rapid development of the US shale sector was forecast to result in very low US gas prices in the 2020s, but in late August they peaked well over $9/MMBtu, a result of capital retrenchment amongst US drillers, limiting growth in associated gas production, and burgeoning demand, particularly for US gas exports.

Nonetheless, US gas prices remain cheap in the context of the LNG market, which saw spot prices of $71/MMBtu on August 25. Devon Energy’s interest in a tolling agreement reflects the huge margin between domestic US gas and spot LNG, even if US gas prices are much higher than had formerly been anticipated.

But how will the market look in 2026, when the first phase of Delfin LNG is expected on-stream?

Building the FLNG vessels takes four years each and limited shipyard capacity for such vessels may prove a problem. South Korean shipbuilders’ order books are chock full of container and LNG carrier orders, which reach out more than three years at present. An FID this year is important for Delfin to book a slot for vessel construction.

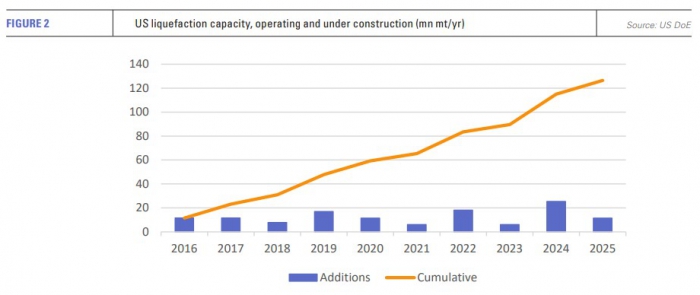

The 2026 timing means Delfin LNG will arrive on the scene roughly at the same time that Qatar’s giant LNG expansion starts to come on-stream alongside a number of other major US LNG developments. This also provides four years for Europe to adjust to the sudden shock of its loss of Russian pipeline imports.

Although the outlook for LNG demand looks strong over the next decade, forecasting the competitiveness of US LNG four years hence is no easy calculation in the current febrile market.