Latin America’s Hydrocarbon Production Is Key to Global Energy Security [Gas Expert Insights]

The Big Picture

- Latin America holds the world’s second largest hydrocarbon reserves, with oil and gas production surging in Guyana, Brazil, and other areas.

- U.S. and European companies and policymakers are looking to the Latin America region for energy production and security, as the Ukraine and Middle East experience increased geopolitical risks.

- To promote global energy security, the U.S. and local government policies should support Latin America’s hydrocarbon development, along with significant investments in decarbonization partially funded by hydrocarbon exports’ revenues.

Summarizing the Issue

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Latin America is home to the second largest hydrocarbon reserves in the world after the Middle East; but until recently, production was in decline due to political risks and state intervention. However, prospects for change are optimistic. Since 2022, Latin America’s regional oil production is up, largely due to surges in Guyana and Brazil, and production promises to continue growing at least for the rest of the decade. In addition, there are good prospects for increased global natural gas exports from the region, largely from Argentina and Venezuela. Heightened geopolitical risks posed by two of the other major producing regions — Central Asia and Middle East — have turned the attention of U.S. and European companies and policymakers to the relatively geopolitically stable and open Latin America region.

Despite efforts to reduce global fossil fuel consumption, global hydrocarbons demand has kept growing. U.S. and European sanctions imposed on Russia and Iran have been limited by the need to mitigate surges in oil and gas prices as well as the risks of overdependence on other members within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+). Increases in U.S. and Canadian hydrocarbons production have been critical in moderating the economic consequences of these geopolitical disruptions, and Latin America has also been a major contributor to sufficient supplies of fossil fuels.

Expert Analysis

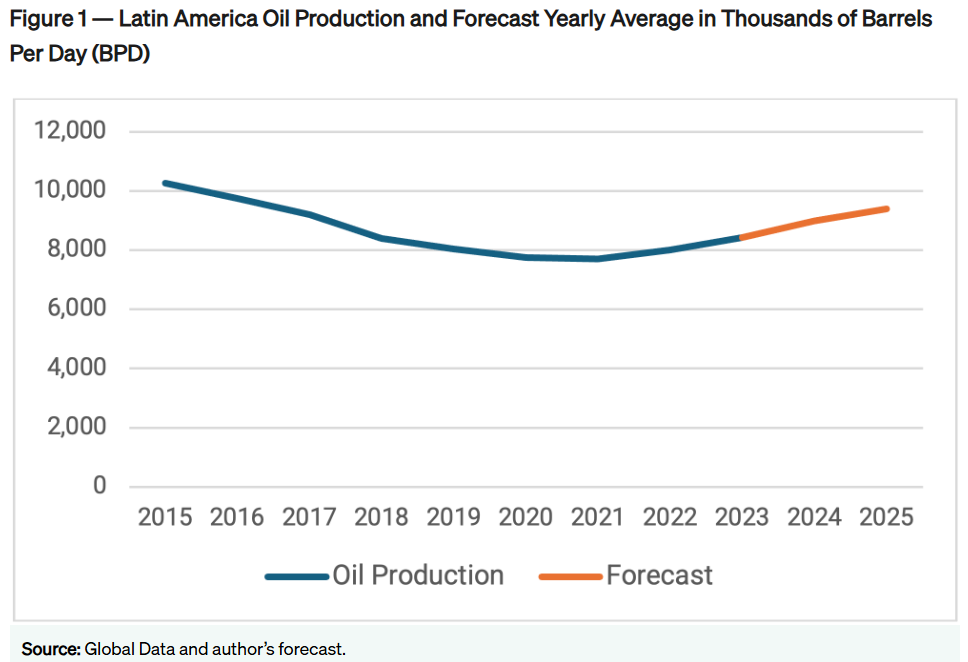

After seven years of steady decline leading to an accumulated drop of 25% — led by falls in Venezuela and Mexico — Latin America’s crude oil production has recovered by more than 9% over the last two years (Figure 1). The recovery has been led by significant growth in Guyana and Brazil, with additional increases in Argentina and Venezuela. Brazil and Guyana are set to continue their notable upward trajectory in the next few years, with the only question being the pace of development in their prolific offshore production levels. Both countries are open to private investment and have a record of respecting the property rights of private investors.

Guyana’s and Brazil’s Success Stories

Guyana’s oil production is one of the most remarkable success stories in the last few decades. Offshore oil was first discovered there by Exxon in 2015. Production started in 2019, and, by the end of the first quarter of 2024, it had reached 600,000 barrels per day (bpd). The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts that Guyana’s production will surpass 800,000 bpd in 2025, adding more than 300,000 bpd in two years. In turn, Brazil’s production is expected to grow by more than 250,000 bpd in the same period.

These increases will make Guyana and Brazil, along with the U.S. and Canada, the largest sources of production growth in 2024–25, allowing Latin America to surpass the production levels of 2017. In fact, it is estimated that Latin America will provide the largest increase in output among private international oil companies for the remainder of this decade.

In Brazil, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is following a pragmatic approach, pushing forward investments in hydrocarbon exploration and production while pursuing significant investments in decarbonization. This could prove to be a smart strategy that balances energy security, development, and climate considerations.

Argentina’s Outlook

Argentina should continue to grow, although arguably below its potential, due to macroeconomic instability and political risks. Still, the pro-business Milei administration is working to improve the industry environment to develop the country’s massive shale resource base, which would call for horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing to extract oil and gas in rock formations with low permeability. Even though it is years away, Argentina could become a major source of liquified natural gas (LNG) exports if it can deploy the needed infrastructure investment to ship the gas overseas.

Other Latin America Countries’ Challenges

Finally, Venezuela is a major question mark. Despite having massive resources, low geological risks, and significant brownfields ready for investment, Venezuela’s political risks, deteriorated state capacities and infrastructure, and its fraught relations with the U.S. all make large production recovery unlikely in the short term. Unless there is regime change, the most probable scenario is one of modest recovery led by Chevron’s investment, which has a U.S. license to operate in the sanctioned country.

In contrast, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico — as well as Trinidad and Tobago — are all expected to continue their output decline. The recent presidential election in Mexico points toward continuity in polices that closed private investment opportunities and exacerbated the financial problems of Mexico’s national oil company Pemex. In Colombia, the Petro administration has banned fracking and halted bidding rounds for exploration, making the recovery of production over the next few years unlikely.

A Welcome Surge

Overall, Latin America’s hydrocarbons surge is a welcome development for global energy security. If global hydrocarbons demand does not fall rapidly over the next decade, Latin America’s contribution to supply will be crucial to mitigating geopolitical energy risks. In addition, revenues generated by additional oil and gas exports would boost economic growth and government revenues in the exporting countries.

Impact on Climate Change

The downside of increased hydrocarbon extraction is the parallel increase in carbon emissions. However, if global demand for hydrocarbon is not abated, supply will rise to cover that demand. Furthermore, with the exception of Venezuela, the areas where Latin America’s oil production is rising all have below average emissions, meaning they are better options than the alternatives from an emissions perspective. From a climate perspective, the industry focus in the short term should be on reducing natural gas flaring and venting, particularly in Mexico and Venezuela — both of which have a greater impact on global warming.

Policy Actions

Based on this analysis, U.S. policy and Latin American countries should:

- Encourage hydrocarbon production in the region, particularly in lower emission fields.

- Support significant reductions in natural gas flaring and venting and/or penalize excessive emissions.

- Earmark fiscal revenues from hydrocarbons for emissions mitigation in the most cost-effective areas, which include hydrocarbon extraction, natural gas flaring and venting, and land/forestry management.

The Bottom Line

The emergence and escalation of conflicts in the Ukraine and Middle East have increased the importance of Latin America’s hydrocarbon reserves and its contribution to global energy security. Growth in the region’s oil production and its prospects for increased global natural gas exports both underscore the need for U.S. and the region governments’ policies that support Latin America’s hydrocarbon development as well as significant investments in its decarbonization efforts.

Written by Francisco J. Monaldi, originally published by Baker Institute.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Gas Expert Insights are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.