Project spotlight: Vista Pacifico [Gas in Transition]

Pacific Coast North American LNG exports are long overdue, but should in coming years start to reap the rewards of shorter sea routes to the dynamic growth markets of Asia, avoiding the costs and risks of Panama Canal transits.

The only two west coast North America LNG projects currently under construction are the Shell-led, LNG Canada and Sempra Energy’s Costa Azul project in Mexico, neither of which, notably, are in the US, although the latter will take US pipeline gas as feedstock.

But, in a recently-announced deal with Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), Sempra Energy now looks well placed to progress its second US-fed Mexican LNG project, Vista Pacifico.

Project details

In its export licence application to the US department of energy in 2020, Sempra asked for permission to export 200bn ft3/yr (4.1mn metric tons/year) of US gas delivered by pipeline through Mexico from Vista Pacifico to countries with which the US has a free trade agreement (FTA) and to non-FTA countries. The project will have a nameplate capacity of 3-4nm mt/yr. At the time, the company expected to start construction this year for completion in 2025.

The project site near Topolobampo in Sinaloa state is 370.66 hectares, about 500 km south of the US-Mexican border. Vista Pacifico will consist of a single LNG train, a gas treatment plant for the removal of mercury and acid gas, dehydration and natural gas liquids removal and fractionation. It will also host a single 180,000-m3 storage tank, marine jetty, ground flare equipment, piping interconnections and associated utilities.

Gas supply could be sourced from a number of cross border pipelines such as Trans Pecos and Comanche Trail in west Texas and Sierrita in Arizona, allowing access to gas from multiple US shale basins.

Freight advantage

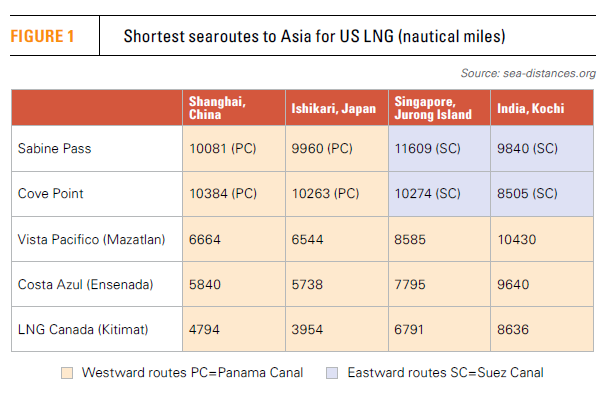

LNG plants on North America’s west coast will have a significant freight advantage over US exporters on both the Gulf and East Coasts, for which there are four possible routes to Asia: westwards through the expanded Panama Canal or around the far south of South America via Cape Horn or the Magellan passage; and eastwards, rounding South Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, or heading through the Mediterranean and taking the Suez Canal into the Red Sea and onwards to Asia.

There are big differences in the distances travelled (see table 1). From the US Gulf Coast Sabine Pass LNG plant, a Panama Canal transit to Shanghai is 10,081 nautical miles (nm) (18,670 km), compared with 17,248 nm via Cape Horn, 13,854 nm via the Suez Canal or 15,098 nm via the Cape of Good Hope. Vista Pacifico would cut the distance to Shanghai to just 6,664 nm, a reduction of 34%.

For the US East Coast Cove Point LNG plant, the Panama Canal offers a distance of 10,384 nm to Shanghai, Cape Horn 16,684 nm, Suez 12,519 nm and the Cape of Good Hope 14,459 nm. Given the greater distances, navigational difficulties and harsh weather conditions, the Cape Horn/Magellan Strait routes are rarely used.

Nautical distances are often very different from the mental geographic picture one might hold and Asia covers a huge area. The distance from either Cove Point or Sabine Pass to Singapore’s Jurong Island is shorter, for example, via the Suez Canal than the Panama Canal. Eastward routes to Kochi in India are also shorter for Sabina Pass and Cove Point via the Suez Canal than for Vista Pacifico taking the westward route.

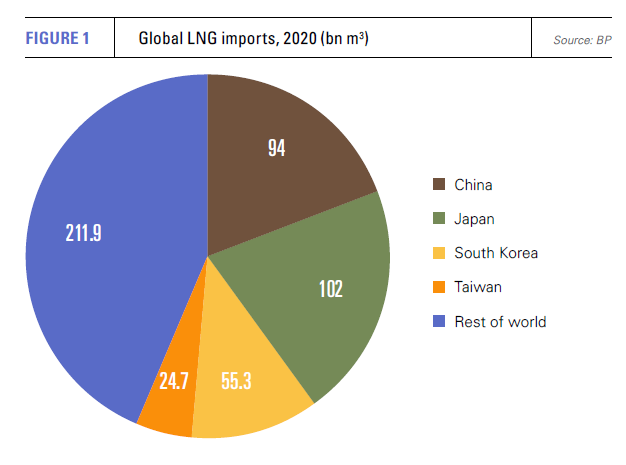

Distance is by no means the only factor in LNG shippers’ route choices; journey times and costs are affected by weather conditions and canal transit times, among other factors, but the freight case for West Coast LNG exports is clear cut as they avoid Panama Canal tariffs, potential delays as a result of canal congestion, and have shorter distances to the key LNG markets of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, which, in 2020, together accounted for 56.6% of global LNG imports (see figure 1).

According to Shell’s annual LNG market outlook, global LNG is expected to almost double between 2020 and 2040 to around 700mn mt/yr. Nearly 75% of this will be driven by Asia demand, Shell estimates, making competitiveness in Asian markets a key draw for LNG developers.

Mexican deal

Taking on a project in a foreign country introduces a whole new set of challenges for developers and Mexico’s historically complex political gyrations around the issues in foreign inward investment and resource nationalism are no exception. The election of president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) in 2018 swung the pendulum back towards the resource nationalist camp and Sempra Energy has had to sway with the prevailing political winds with regard to its Costa Azul project.

Now, however, it appears to have struck a deal which will see Costa Azul Phase 1 progress and land it additional Pacific coast LNG export capacity in the form of the Vista Pacifico project. This would supplement Costa Azul Phase 1’s 3.25mn mt/yr capacity and address the deteriorating prospects for Phase 2, owing to a lack of US-Mexican pipeline capacity.

To this end, Sempra Infrastructure announced on January 31 that it had signed a non-binding memorandum of understanding (MoU) for a number of projects which reflect not just its own development goals, but those of the Mexican state. The MoU with CFE included the joint development of Vista Pacifico, construction of an LNG regasification project at La Paz, Baja California Sur, and a resumption of operations for the Guaymas-El Oro pipeline in Sonora.

Vista Pacifico will be a joint development between Sempra and CFE. CFE is an LNG importer and this would provide it with a stake on the production side, although the terms of the agreement are as yet unknown. Given the political situation, buy-in from a state-owned entity looks like a shrewd move, even if it may appear as a concession.

Pipeline problems

The Guaymas-El Oro pipeline was completed in 2017 under a build-own-operate contract between Sempra and CFE, but was shut down in August the same year following sabotage attributed to indigenous Yaqui group, who oppose its operation. The pipeline is 330 km long with a 30-inch diameter and capacity of 510mn ft3/d, equivalent to 5.3bn m3/yr.

The sabotage affected a roughly 15-km section of the line which crosses Yaqui land. The Yaquis say they never gave permission for its construction. The new agreement with CFE provides for a re-routing of the pipe around the disputed section with the new section expected to be 70-90 km long.

The pipeline interconnects with the north-south, 430-km, 2.1bn-m3 El Oro-Mazatlan pipeline, which together with the 6.9bn-m3 El Encino Topolobampo line forms the El Encino-Mazatlan system, which is a key component of Mexico’s north-northwest gas system.

The El Encino Topolobampo line connects with the Ojinaga-El Encino pipeline and then runs into the US on the intrastate Trans-Pecos line, which connects to the Waha gas hub in Texas. The Guyamas-El Oro pipeline is also linked in the north to the Sasabe-Guyamas pipeline, which interconnects at the US Arizona border with the expanded Sierrita gas pipeline. The latter could potentially deliver gas to the proposed Mexico Pacific and AMIGO LNG plants in Sonora state.

Gas delivered via the El Encino Topolobampo pipeline powers a number of gas-fired power plants at Topolobampo and plants at Ahome and Mazatlan. Bringing the Guaymas-El Oro pipeline back into operation will allow gas to replace diesel at thermal power plants situated in Guaymas, saving CFE significant fuel costs, as well as reducing both local electricity prices and greenhouse gas emissions.

Baja California Sur

Displacing carbon heavy and expensive oil-fired generation also lies behind the agreement on an LNG regasification terminal in La Paz, Baja California Sur. The Baja California peninsula lacks gas pipeline connections, largely owing to its geography. The state runs north-south down the Pacific coast, but is split from the Mexican mainland, except in the north, by the Gulf of California.

New Fortress Energy opened a 2.1mn-mt/yr regasification terminal last year at Pichilingue port in Baya California Sur, designed to supply gas to two open-cycle gas plants, CTG La Paz and CTG Baja California Sur. CFE plans to build additional gas plants in the area and is therefore keen to establish additional LNG supply capacity, which could now be fulfilled by the new regasification facility proposed in the MoU.