'There's No Way to Tell' How Much Gas the U.S. Can Produce

First of two articles

About 100 geologists and engineers are completing a new answer to a crucial issue for energy producers, consumers and policymakers: How much natural gas is buried a mile or more down in America's shale rock?

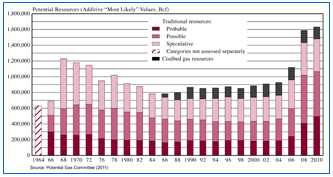

Two years ago, this team -- the Potential Gas Committee directed by John Curtis of the Colorado School of Mines -- fixed the most likely amount of U.S. natural gas that could be produced from all sources with today's technology at 1,898 trillion cubic feet (tcf). Add 273 tcf of already "proved" reserves reported by energy companies, and the United States was sitting on 2,100 tcf at the end of 2010, according to the committee.

For a country that consumes 24 tcf of natural gas a year, the total resource estimate suggested an abundance that could last nearly a century -- an outlook endorsed by President Obama and leaders throughout the industry.

There is no doubt that the volume of shale gas beneath the country is immense. But estimating the likely production of gas from shale rock is confounding.

Is there 30 years of gas? One hundred years?

"There's no way to tell," said economist Alan Krupnick, director of Resources for the Future's Center for Energy Economics and Policy. The shale gas phenomenon is too new, he said. "We just don't know how it's going to work out."

"We just don't know how it's going to work out," economist Alan Krupnick, director of Resources for the Future's Center for Energy Economics and Policy, says of the shale gas phenomenon. Photo courtesy of Resources for the Future.

Even if geologists could pinpoint the amount of gas in shale formations, gas production depends on the interplay of gas prices and drillers' costs and profits. Only a portion of the shale gas resource can be profitably extracted at today's relatively low prices, economists note.

"We think the resource is vast," said John Staub, who heads the oil and gas estimates team for the Energy Information Administration. But estimates of shale gas resources and reserves are still based on a small sample of actual wells. A year ago, EIA dropped its estimate of "unproved technically recoverable resource" for shale gas to 482 tcf, from the year-before estimate of 827 tcf.

The biggest part of the downgrade was an even steeper cut in the estimate for the Marcellus Shale, which runs from New York to West Virginia. It dropped from 410 tcf to 141 tcf. EIA calculated that it would take more than 90,000 wells to deliver the expected shale gas volumes from the Marcellus play, but between 2005 and the end of 2011, just 4,886 unconventional wells had been drilled. The state's delayed gas production reports showed overall actual results were significantly less than gas developers had announced.

"Everybody has the 'Lake Wobegon' effect: 'All our wells are better than average,'" said U.S. Geological Survey research geologist Ronald Charpentier. "There is a lot of interpretation of the data -- both in production and geology."

"We're still a few years away from seeing how some of these new discoveries are going to play out," said James Coleman, task leader in the USGS Energy Resources Program.

"We have decades and decades of technically recoverable natural gas as we see it ... a large endowment of natural gas in the U.S. that can contribute more to its energy policy, but it is not the solution to the needs of the country," Curtis said. "It isn't a bridge to hydrogen future. It is part of the future as we transition off of fossil fuels. "

'Best assessment of truth'

Curtis' team is only considering the size issue -- the amount of gas that can be produced with today's technology. The Potential Gas Committee's calculations do not consider how changes in the price of natural gas will affect production.

"The '100-year supply' is often attributed to us, which is not correct," Curtis said. "We report our work on the resource. Whether we have a 30-year supply or a 100-year supply, we go with what we publish," he added. "This is not truth. This is a best assessment of truth."

There is a cumulative buildup in knowledge from the ongoing assessments, he said.

"It's like raising teenagers," Curtis said. "You know you're going to be wrong, but you're going to try to get better every time. So we all work together on this to see what works best."

John Curtis leads the Potential Gas Committee, which seeks to determine how much natural gas is buried in America's shale rock. Photo courtesy of the Colorado School of Mines.

The committee's 2010 total was 74 percent higher than the 2000 estimate in large part due to the revolution in shale gas production. Shale gas was just 2 percent of the U.S. total in 2000, but it accounted for 687 tcf, or 36 percent, of the 1,898 tcf in the 2010 estimate. (One trillion feet of gas can heat 15 million homes for a year.)

Curtis said that the new number, updating the 2010 report, has not yet been pinned down, but the signs from the assessment teams are bullish.

"We'll have to see how the numbers shake out," he said in an interview. "There hasn't been any groundswell of [negative] information" about the new survey, he added.

Curtis' volunteers build up their assessments by estimating gas resources in 90 offshore and onshore geological provinces. "We look at everything on a formation-by-formation basis, so it's a bottoms-up approach," he said. "And the volunteers we use are working these basins for a living."

The researchers are able to draw on internal company data about well drilling and production results, he said.

"The level of data we're looking within the company is the actual raw data, the seismic data, the production decline curves," Curtis said about his team. "They aren't looking at what the company says they have. ... They look at the data within the company and draw their own conclusions."

The uncertainties require the committee to chart a range of possible gas supplies, from least to most likely.

The committee's assessment is built up from separate estimates of "probable," "possible" and "speculative" gas supplies in each of the 90 onshore and offshore U.S. geological provinces. Resources are considered probable even if not yet confirmed if they are connected to fields where gas is currently being produced. Possible resources could come from new fields in the same geological formation where the rock structure may differ, creating more uncertainty. Estimates of gas in typically deep formations or other nonproducing areas that have not yet been drilled are labeled speculative.

For example, the committee's assessment for the Appalachian Basin region, which includes the Marcellus and Utica shales, includes a minimum probable volume of 29 tcf, a most likely figure of 63 tcf and a maximum of 133 tcf.

The most likely "probable" and "possible" figures were combined statistically to get a most likely total for that shale gas area, which was added to other totals to produce the committee's 687 tcf of estimated shale gas resources in 2010. (The committee didn't list a "speculative" figure for the Appalachian Basin.)

Curtis finds support for his team's work in a separate assessment by the Geological Survey, centered on the extensive Marcellus Shale formation, which ranges through upstate New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee. USGS periodically reviews individual shale plays. This month USGS plans to go behind closed doors to assess the Bakken Shale formation in North Dakota.

The Potential Gas Committee's biennial assessments of potential gas resources from 1964 through 2010 are illustrated here by category. Courtesy of the Potential Gas Committee.

USGS, like the Potential Gas Committee, provides a range of expected shale gas volumes, not a single estimate. Its Marcellus Shale estimate, in 2011, said the formation was most likely to hold at least 84 tcf of undiscovered, technically recoverable natural gas. There was a 95 percent chance that it held at least 43 tcf and a slight, 5 percent chance of as much as 144 tcf.

The span of estimates is the result of computer modeling that factors in key shale play variables, such as the thickness, depth and age of the shale play, the porosity of the rock, and the production from current wells and wells in similar formations, said USGS's Coleman.

Larger mysteries ahead

Some factors paint a clear picture. Others leave many unsettled questions about the richness of the shale gas resource.

For example, the size and shape of the shale formations is among the longest-studied and best-defined variables, said Coleman's colleague, Charpentier. "You can tell where the shale is, and isn't," he said. There is much less certainty on other issues, such as estimating how much of the Marcellus gas or oil is concentrated in prime exploration zones called "sweet spots," versus less potentially productive areas. The low estimate for the hydrocarbons in sweet spots is 10 percent, the high 75 percent.

Shale rocks can be particularly tough to figure out, Coleman said. "There is greater uncertainty in the shale formation because we're relying on very small pores to store and release the hydrocarbons," he added. "We're looking at them in terms of a sample the size of my hand and trying to extrapolate over 1,000 feet or so. And we don't have a good understanding of the distribution of the pore spaces that host the oil and gas."

Each of the variables is assigned a range of possible outcomes, low to high. Then different results for each variable are combined in random ways in a computer model to create a statistical breakdown of all possible outcomes for the shale play.

"We will do 10,000 iterations and you have 10,000 answers," Charpentier said. From that computer run, the probability of various shale resource estimates emerges, Charpentier said.

The problem comes when there is a wide range of possible outcomes, said Richard Nehring, president of the Nehring Associates Inc. consulting firm in Colorado Springs, Colo., and chairman of the Committee on Resource Evaluation for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

"People latch on to one number, and that is a big mistake to think that is the answer," Nehring said. "They say, 'Give me the number,'" because they're uncomfortable with uncertainty. "Instead you're dealing with a very large range of numbers, and if you ignore that range you do it at your peril, because you can make some very bad decisions in thinking you don't have to worry about gas supply," he said.

"Just how much gas supply do we have?" Nehring asked. "We can't make policy on the basis of an assumed 100 years of supply. If you only have 30 years of resource left, that doesn't take us through the midcentury mark. If it's 130, you have a lot more options, you can think about gas exports."

It is challenging enough to estimate the size of the gas resource. An even larger mystery is how natural gas prices will move in the future and how that will affect production, he said. That will be the product of many thousands of unpredictable decisions to invest, produce and buy gas in the years and decades ahead.

"We're really operating in a state of ignorance," Nehring said. "The only thing that overcomes that is the experience of time."

Peter Behr, E&E reporter

Republished from EnergyWire with permission. EnergyWire covers the politics and business of unconventional energy. Click here for a free trial

Copyright E&E Publishing