NGW interview: Dieter Helm [NGW Magazine]

NGW: The theme of your presentation at Flame 2019 was ‘Transitions & New Technology – the Carbon Crunch.’ Why is it a carbon crunch?

DH: It is a crunch because the impacts of really addressing climate change will involve significant impacts on the standard of living – because it must include carbon consumption. This means accounting for imports.

UK’s carbon emissions are reported to have fallen by about 30% since 2008. But this accounts only for in-territory emissions. Basing it on carbon consumption, which also includes imports, increases UK’s emissions substantially and paints a very different picture.

Including imports also means that consumption-based carbon emissions become more closely tied to a country’s economic growth.

These are all set out in my two books – The Carbon Crunch

and Burn Out.

NGW: You said that net-zero emissions will be more demanding than the Paris agreement goals and you gave some examples of what it may mean for cars, aviation, manufacturing, etc. Can you elaborate?

DH: It depends whether it is net zero in production or consumption terms, and it depends how fast. If net zero carbon in production, and there is no border adjustment, almost all of manufacturing will be effectively lost, since imports will be rendered more competitive.

Assuming net zero production and if short time scale, and if aviation and shipping are included, it would mean a switch from petrol and diesel to electric vehicles and a sharp contraction of aviation. If net zero consumption, that means no import substitution, but a sharp rise in all carbon-based costs, and a corresponding fall in the standard of living.

These are issues that are not being addressed honestly so far, with the result that, without policy changes, global carbon emissions are forecast by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its ‘New Policies Scenario’ to carry on increasing.

NGW: What is the reality for Europe?

DH: Europe is deindustrialising, and with its economy relying increasingly on the services sector it is reducing carbon production and substituting it its intensive industries with imports. The reality in Europe is:

- Coal will remain until 2040

- Germany’s energiewende failures

- The revolt on the right

- Deindustrialisation

- Carbon consumption, in comparison to the US, is not so good

While Europe is squeezing carbon production at home, it is not cutting its carbon footprint once the effect of imported goods is included - carbon consumption then goes up.

As a result, Europe’s production carbon footprint is going down, but not its overall carbon footprint. Europe should set carbon consumption baselines.

NGW: And what is the reality for the rest of the world?

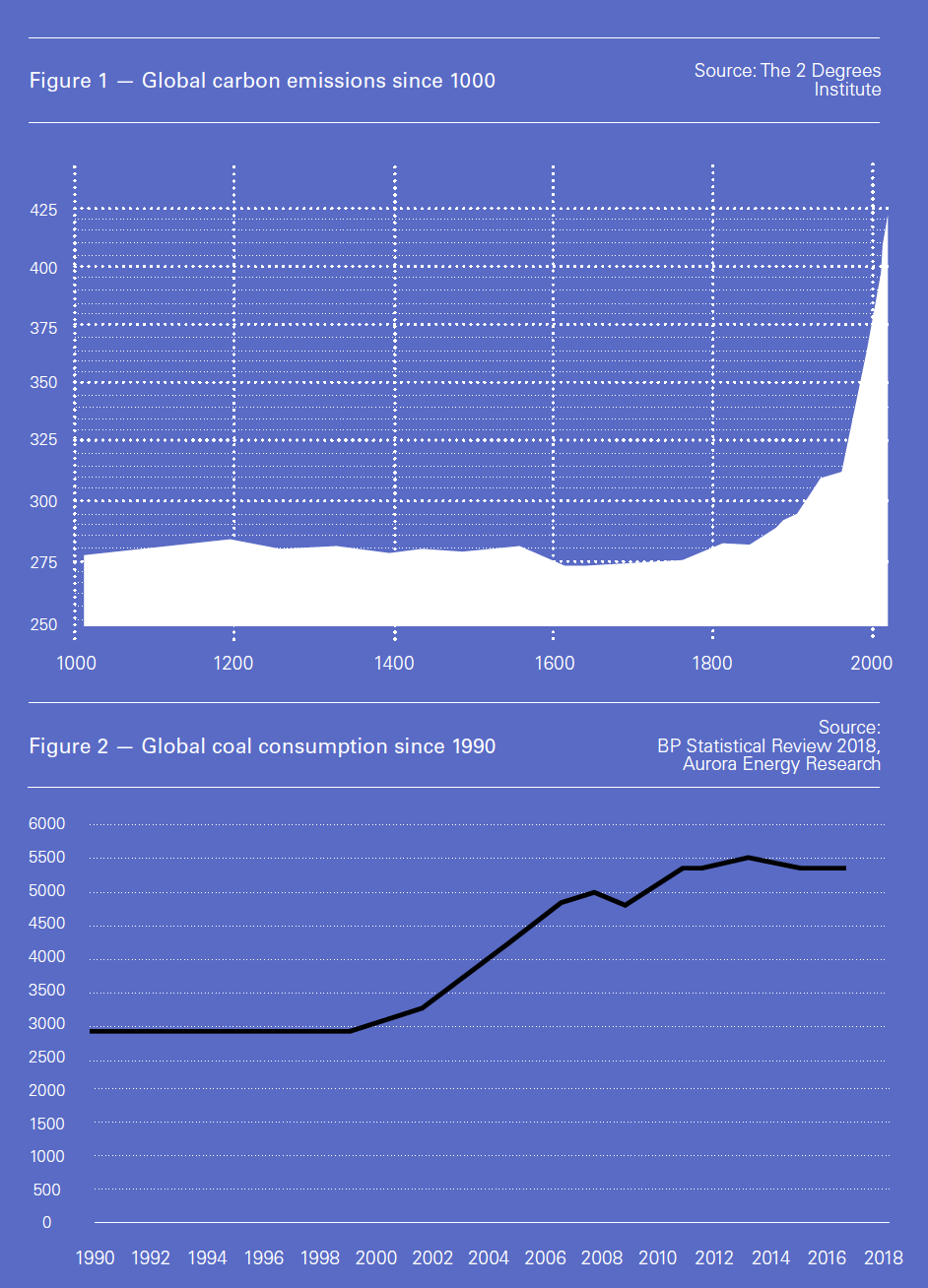

DH: Emissions are rising globally (Figure 1) on a path which is completely inconsistent with 2 °C let alone the Paris 1.5 °C.

For example, as populations and standards of living increase in developing countries, energy consumption and coal use are also increasing, with global carbon emissions and temperatures along with them.

In addition, increasing deforestation is increasing carbon emissions. This must be reversed.

NGW: But the most striking part was your statement that the only honest carbon policy is to concentrate on carbon consumption. Can you explain what this entails, why and the implications?

DH: Carbon consumption measures our impact on carbon emissions. Carbon production measures only the carbon which is emitted within a territory. Hence carbon production can be reduced, whilst at the same time global emissions rise if there is an import substitution. That is what has been going on in Europe – one of the key markets for Chinese and other high emitting countries’ exports.

The equation must also include addressing agriculture, which is a major contributor to global carbon emissions.

NGW: You stated that going for net-zero emissions means that we have to pay a high price – there is a need to tell the truth. What is the truth?

DH: That our consumption remains highly carbon intensive – and we are not paying for the pollution which our consumption causes.

It’s time for a rethink. The claim that global decarbonisation can be done at little or no cost is not real. The truth is that switching from an overwhelmingly carbon to a non-carbon-based economy in the space of just two or three decades will be really expensive.

NGW: As provocative as ever, you called the last 30 years wasted. Why? What happened since 1990 to prompt you to say that?

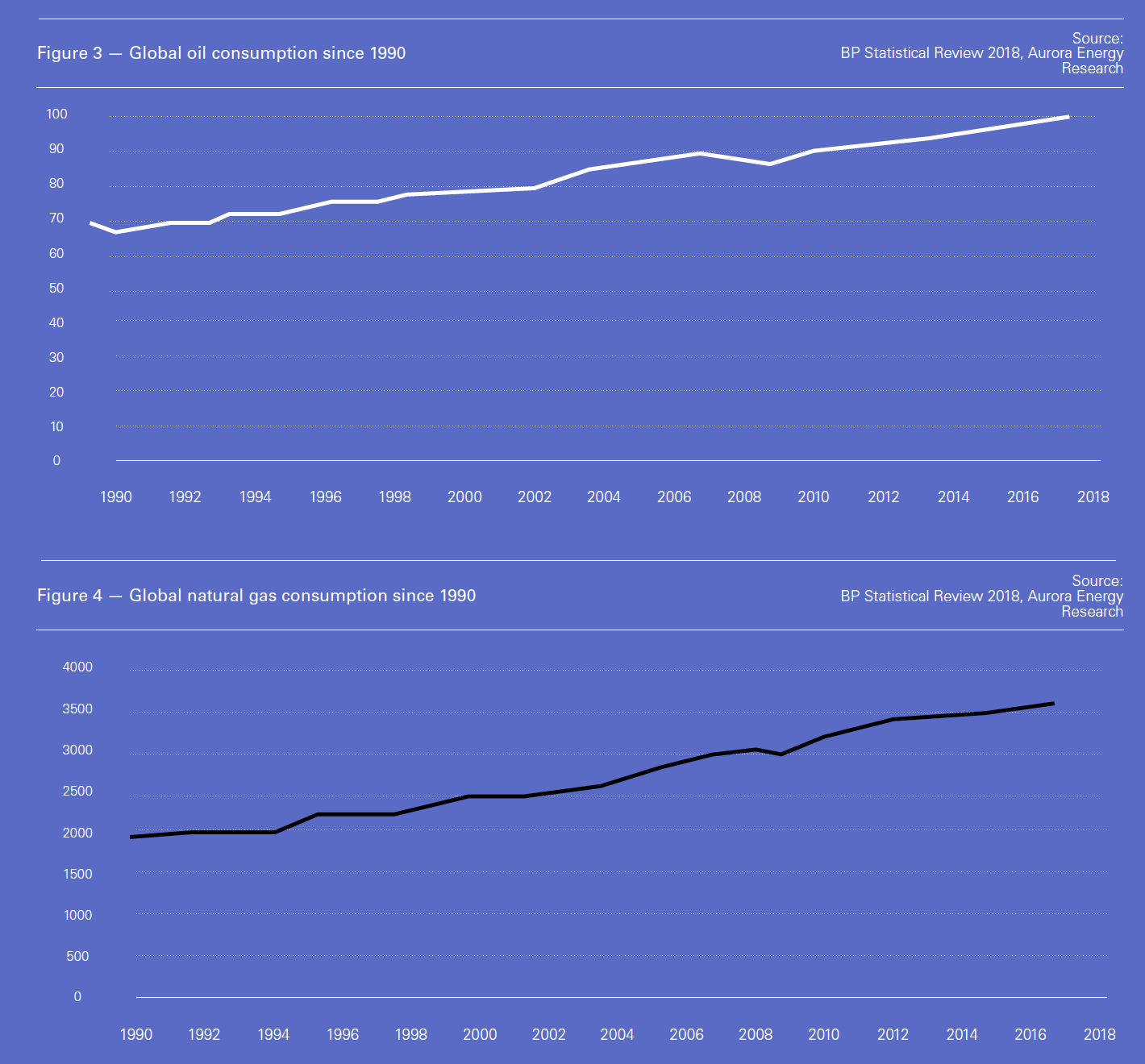

DH: Since the base year of 1990, emission have just kept on going up – we have wasted the first 30 years making little or no progress, despite the costs. For fossil fuels it has been a golden age – demand has been increasing steadily (Figures 2 to 4). In fact oil and natural gas consumption has been increasing since 1990. And with fossil fuel prices going down in real terms, putting more competitive pressure on renewables, these trends are likely to continue well into the future.

It is important to note here that, as pointed out in Burn Out, reduced fossil fuel prices will increase economic and social hardship for countries that are dependent on fossil fuel exports.

If fossil fuel consumption carries on unchecked, it will not achieve Paris agreement goals.

For example, China is not only carrying on increasing its domestic coal consumption, but it is also exporting it by building coal-fired power plants elsewhere in Asia and Africa.

Relying solely on cutting demand for energy is never going to work. Overall, the reality is that without change we remain well on course for exceeding 2 °C warming.

NGW: What do you think will happen during the next 30 years and what do you think needs to be done?

DH: On the current path, there will be lots more carbon emissions and a continuing rise in the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere. The key issues relate to China, India, Africa, Brazil, Indonesia and other fast developing countries. We need to invest in new technologies to help make the transitions and apply a border carbon tax too. There is an urgent need to persuade the Chinese and Indians to reduce their coal industries.

NGW: What should natural gas do to remain relevant during transition?

DH: Gas has a role as a substitute for coal, especially in the fast developing countries listed above and to replace coal in Europe. Gas is the cleanest of fossil fuels and switching from coal to gas reduces emissions fast. The results from the US and the UK demonstrate this.

Natural gas has many advantages over other fossil fuels in the new-technology world, and its demand is likely to go on rising at least in the short to medium term.

NGW: What should Europe do?

DH: That is a huge question! Some answers: use a carbon consumption base for targets not carbon production; apply a border carbon tax; and massively increase the research and development (R&D) spend.

Spending some of the money currently being spent on conventional climate change technologies on R&D to develop new technologies can produce vast benefits: $1bn would be a really big R&D budget.

NGW: You were pessimistic on what Europe will actually do. Why?

DH: It is not doing any of the three recommendations in my previous list. In addition the populist right are both gaining political traction and are largely climate sceptics.

NGW: You made a plea to learn the lessons, focus on the global problem and invest in the future. Can you elaborate? What are your recommendations for the way forward?

DH: The honest approach for the UK and Europe is to set emission reduction targets based on the consumption carbon footprint.

Getting serious about global warming will require transformation in the world’s energy systems through technological advances and innovation.

It is time to get real: climate change is a global phenomenon without much chance of the top-down solution that the UN and the Paris processes promote to provide all the answers. It is better to invest in new technologies that might actually make a difference. Climate change will then get solved.